COMMUNITY-SUPPORTED CONTAMINATION:

Reconfiguring the Framework for PCB Remediation on the Housatonic River

by Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (9.8 MB)

Cover images (left to right): Housatonic River, Berkshire County, Massachusetts; Robyn Van En, originator of "Community Supported Agriculture" (CSA); W.E.B. Dubois, author and civil rights activist; E.F. Schumacher, economist known for his proposals for human-scale and decentralized technologies

© 2018 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

Abstract

Community-Supported Contamination critically reexamines decades of PCB remediation on the Housatonic River, challenging dominant dredging-based cleanup models promoted by the EPA and General Electric. Drawing on environmental design research and existing scientific data, the project reframes contamination as a long-term condition requiring stewardship rather than removal alone. It proposes an alternative framework that integrates ecological function, habitat resilience, and community participation, arguing that remediation strategies must account for biological systems, waste legacies, and social responsibility. By positioning design as an active mediator between contamination, ecology, and governance, the work advances a justice-oriented, place-based approach to river remediation.

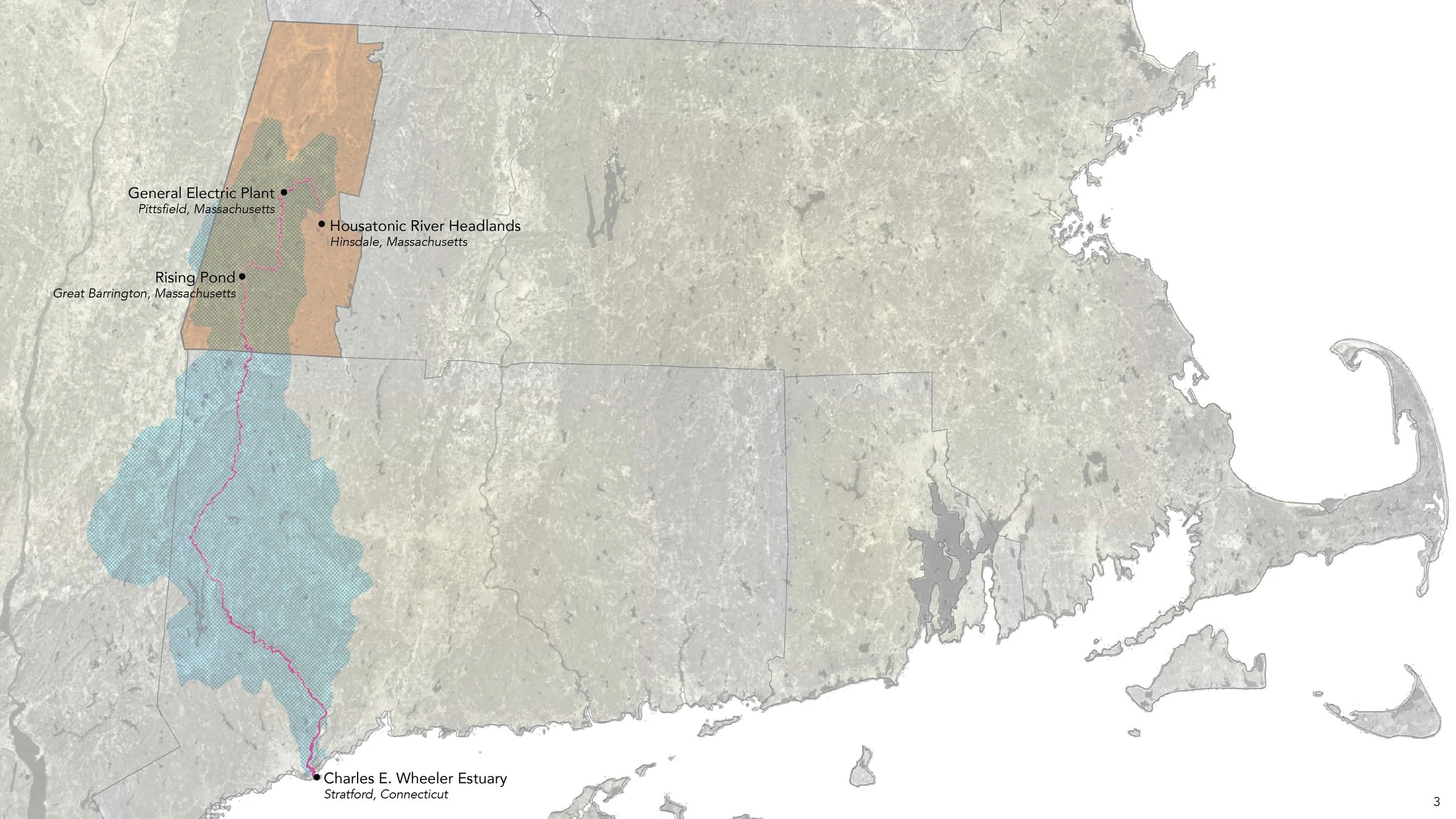

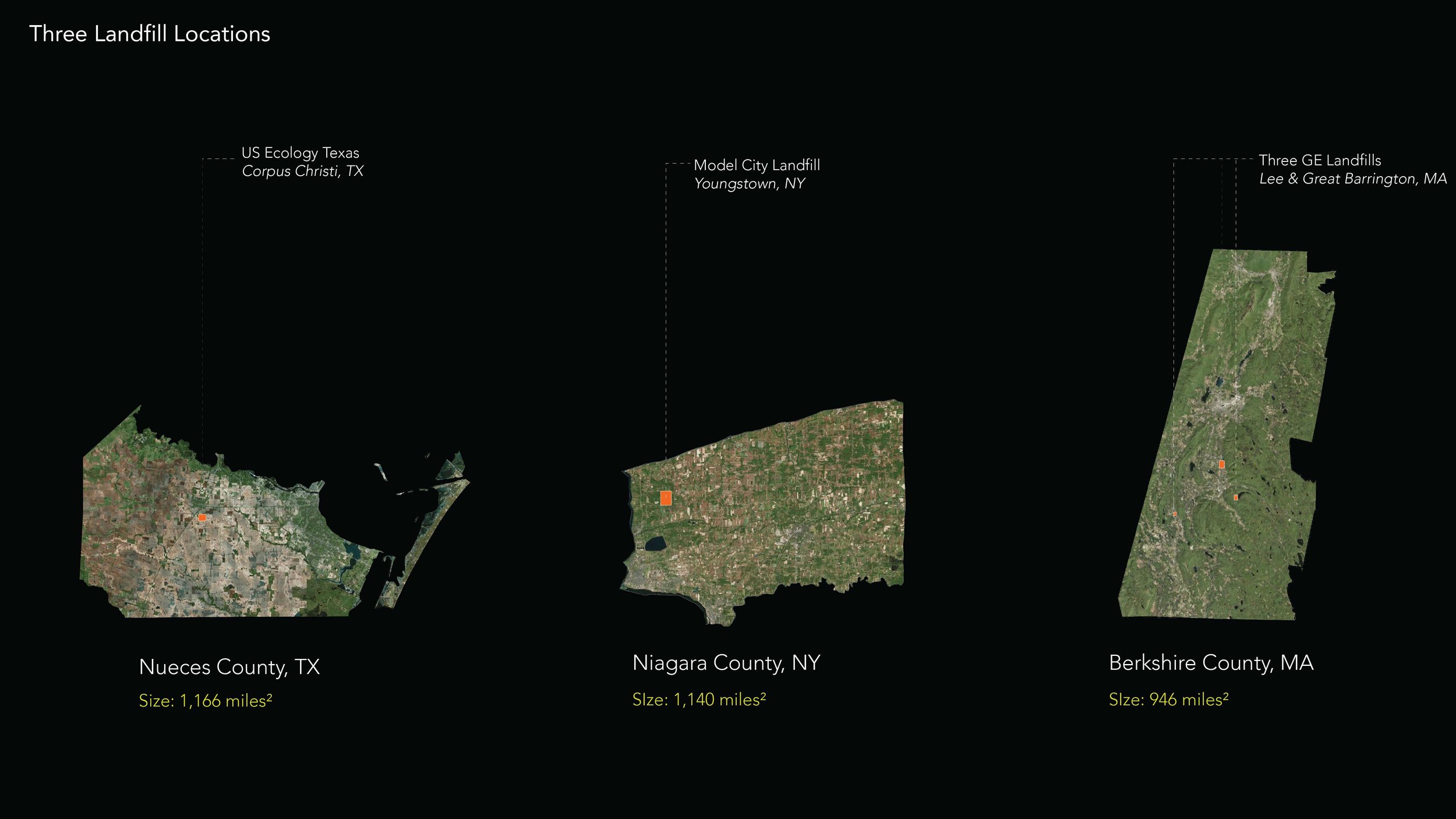

Fig 2.

The Housatonic River watershed, originating in Hinsdale, Massachusetts, and ending in the Long Island Sound in Stratford, Connecticut.

Introduction

Negotiations surrounding the cleaning of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) from the Housatonic River have spanned three contentious decades. In 2007, General Electric Company (GE) under the authority of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) completed the first phase of PCB remediation, dredging 1.5 miles of the river from the GE plant in Pittsfield southward to the confluence of the river’s east and west branches. In 2018, the next phase of river remediation is slated to begin with what the EPA and GE call the ‘Rest of River,’ a $613 million dredging, excavation and soil-sediment disposal project phased over thirteen years.1

“Community Supported Contamination” resists the dig-and-dump operations currently emphasized in ‘Rest of River’ proposals. Instead, Community Supported Contamination proposes a long-term river management strategy, integrating PCB remediation with interventions that target biological function, species biodiversity, habitat connectivity, and ecosystem resilience. I am not a scientist. Rather, I evaluate PCB remediation proposals through the lens of design research. I incorporate the data of others in order to argue for an ecological and ideological framework upon which future river management strategies can be built. An ecologically comprehensive line of questioning allows us to perceive the river not as a volume of sediment in which the bad must be removed, but as an ecological performance consisting of many interconnected biological drivers.

Taking measure of this performance requires a perfunctory understanding of how PCBs affect the environment, which is where my analysis begins. From there, I will evaluate current ‘Rest of River’ proposals in three sections: dredging, in situ capping, and disposal. Ultimately, I evaluate Reach 8 of the Housatonic River in Great Barrington, where I offer specific proposals for interventions that at once reduce contamination levels while also increasing overall ecosystem performance. These proposals should not be seen as foolproof blueprints, but rather as speculative strategies that situate PCB remediation within the longer-term project of stewarding healthy ecosystem function.

This project takes a firm stand against the shipment of PCB waste out-of-state. Engaging a philosophy of local ownership and social justice, this project argues that Berkshire County is equipped to manage its own hazardous waste disposal. In closing, “Community Supported Contamination” positions PCB remediation as merely one component in a longterm management and stewardship plan for the Housatonic River in Berkshire County. “Community Supported Contamination” proposes a coalition of community organizations to manage a continuous system of industrial landscapes along the Housatonic River.

Notes:

—1 Garver, Ben. “GE: ‘No Environmental Benefit’ to PCB Disposal Outside Berkshires.” The Berkshire Eagle. 2 April 2017. Print .

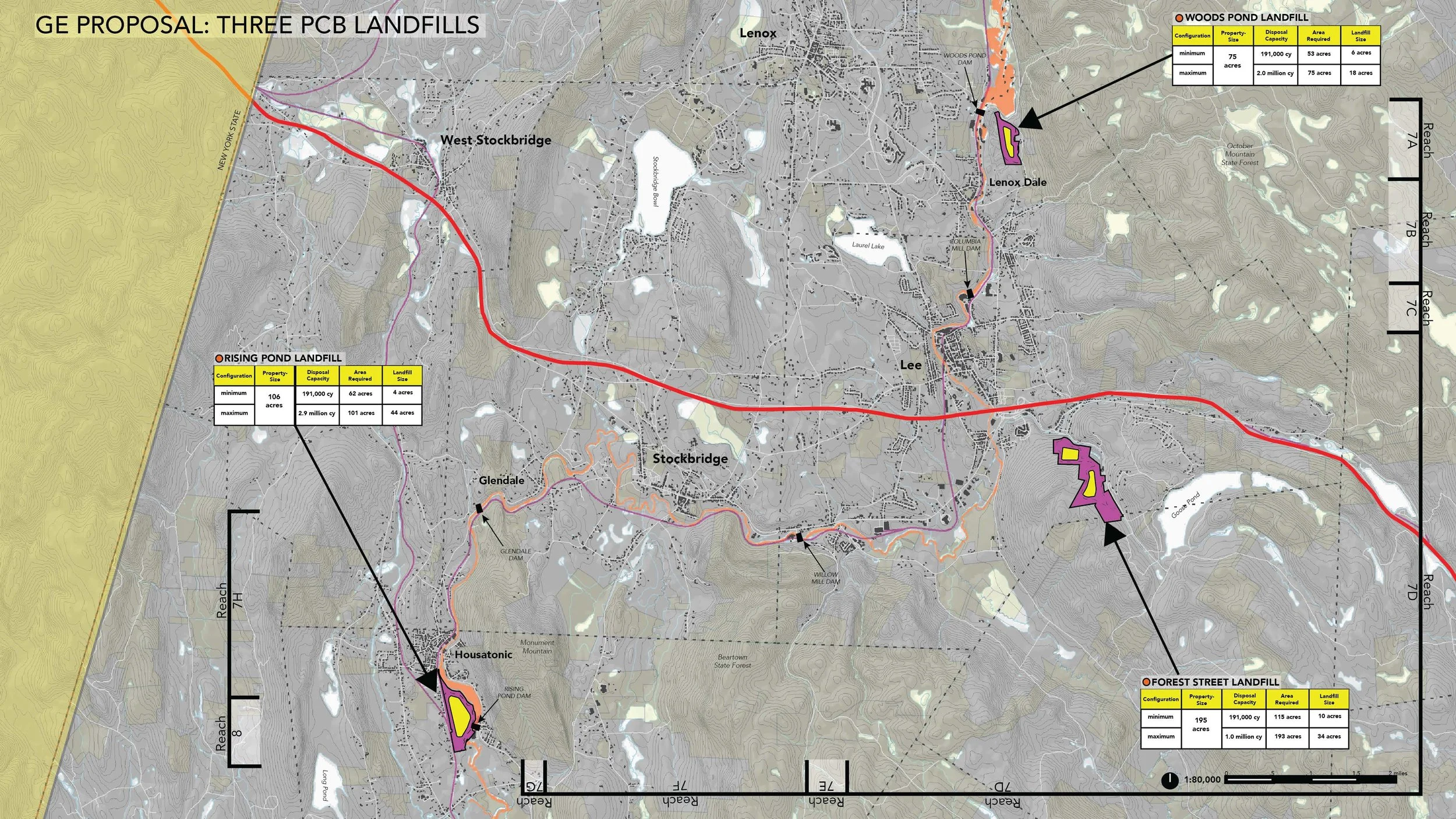

Fig 3.

General Electric Company has proposed to the EPA three local landfills in Berkshire County—the Woods Pond Landfill, the Rising Pond Landfill, and the Forest Street Landfill—for the local disposal of PCBs.

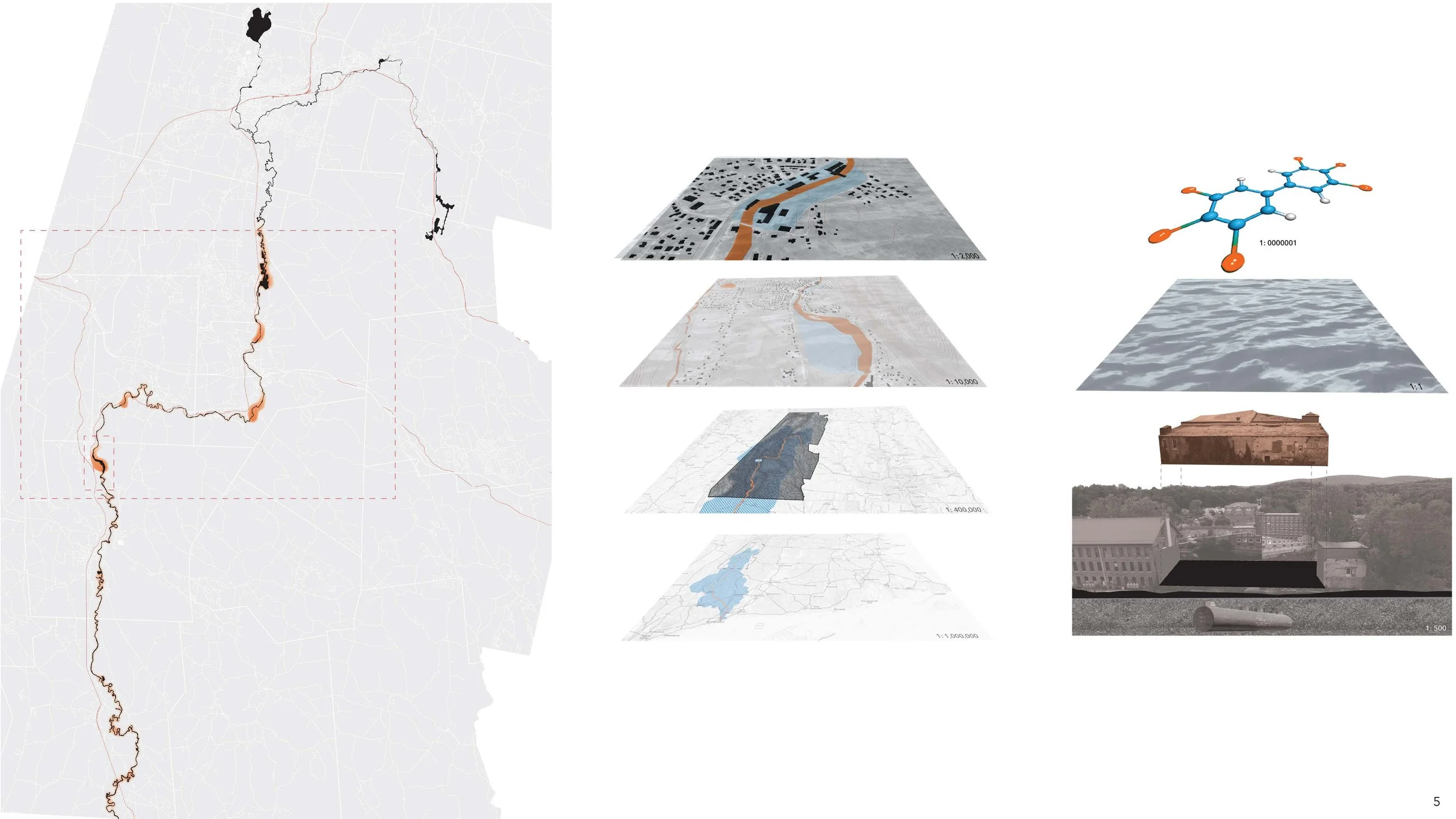

Fig 4.

This project takes a firm stand against the shipment of PCB waste out-of-state. Engaging a philosophy of local ownership and social justice, this project argues that Berkshire County is equipped to manage its own hazardous waste disposal

2. PCB Volatilization: A Cost-Benefit Framework

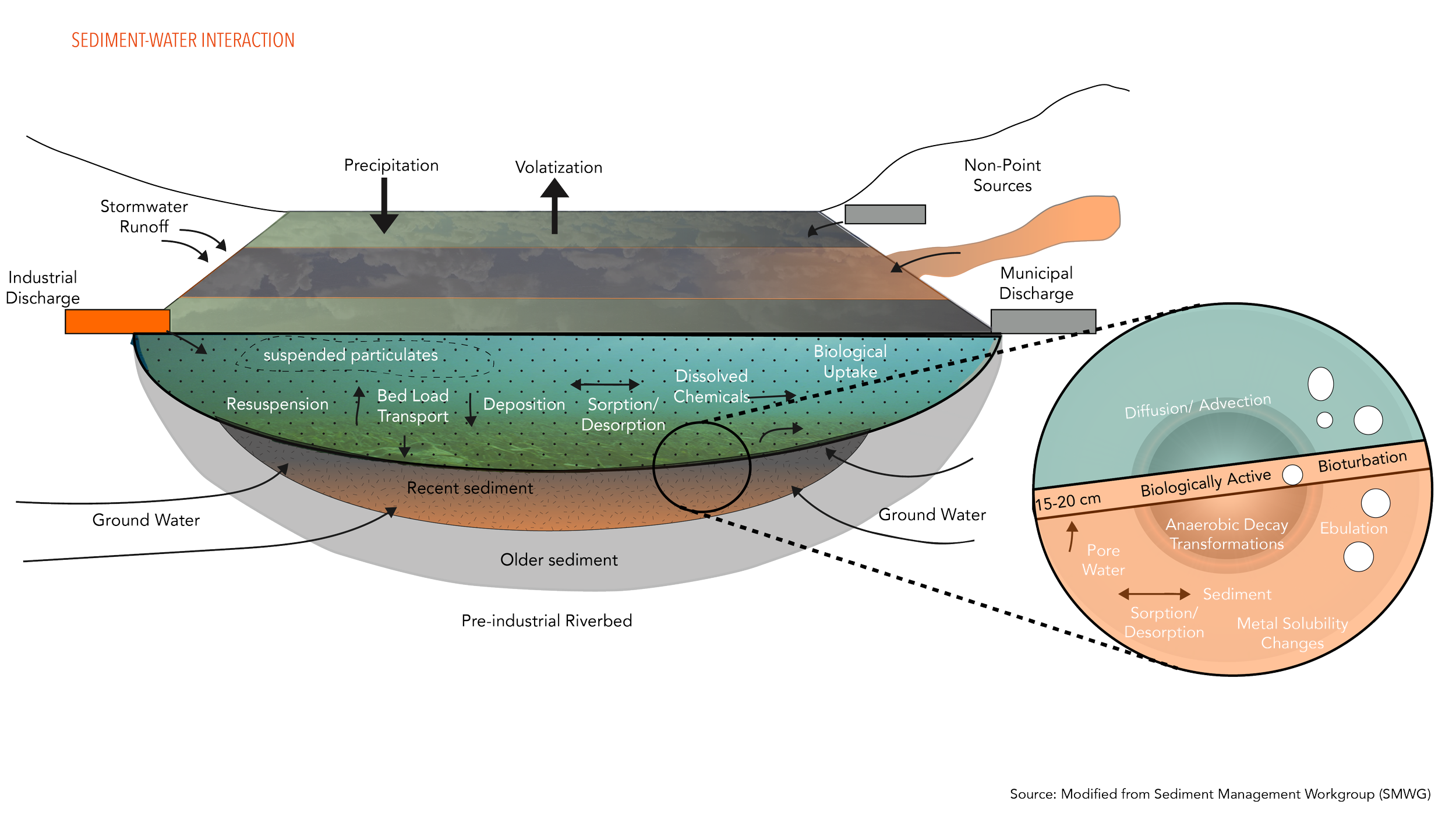

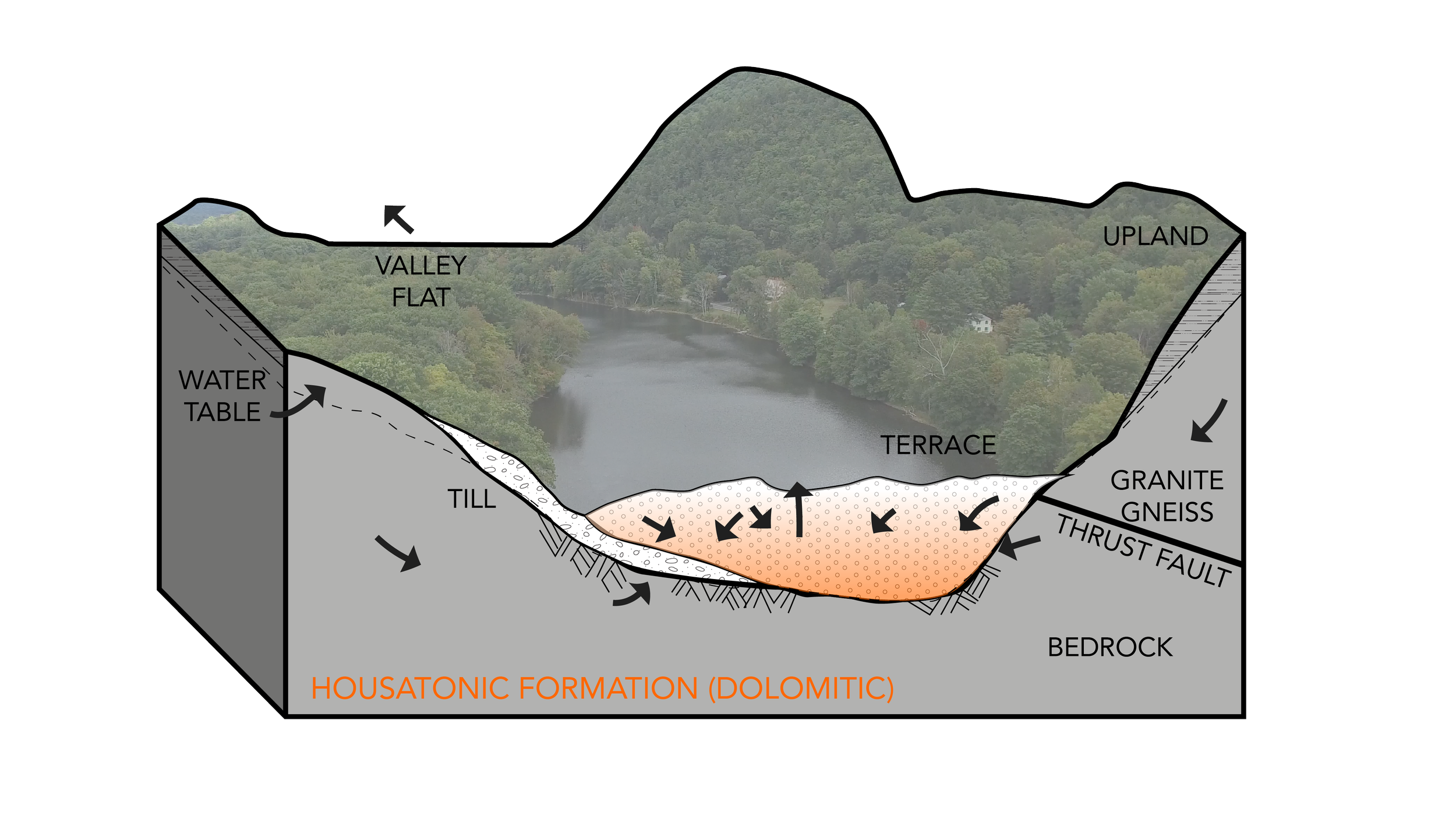

Approximately one million and a half tons of PCBs were dumped by GE into the Housatonic River,2 poisoning surrounding wildlife for the last seventy years. Once discharged, the PCBs were absorbed by fine-grained organic and inorganic particles that were suspended in the water. When stream velocity decreased, such as behind a dam, these particles settled, forming PCB-laden sediment in the river’s bottom.3 [Figure 5] GE primarily released Monsanto’s Arocolor 1254 and 1260 mixtures of PCBs into the river, containing 54% chlorine content and 60% chlorine content respectively. These high chlorine levels make these PCBs profoundly persistent: Arocolor 1254 and 1260 can possibly remain intact in the biosphere for millennia.4

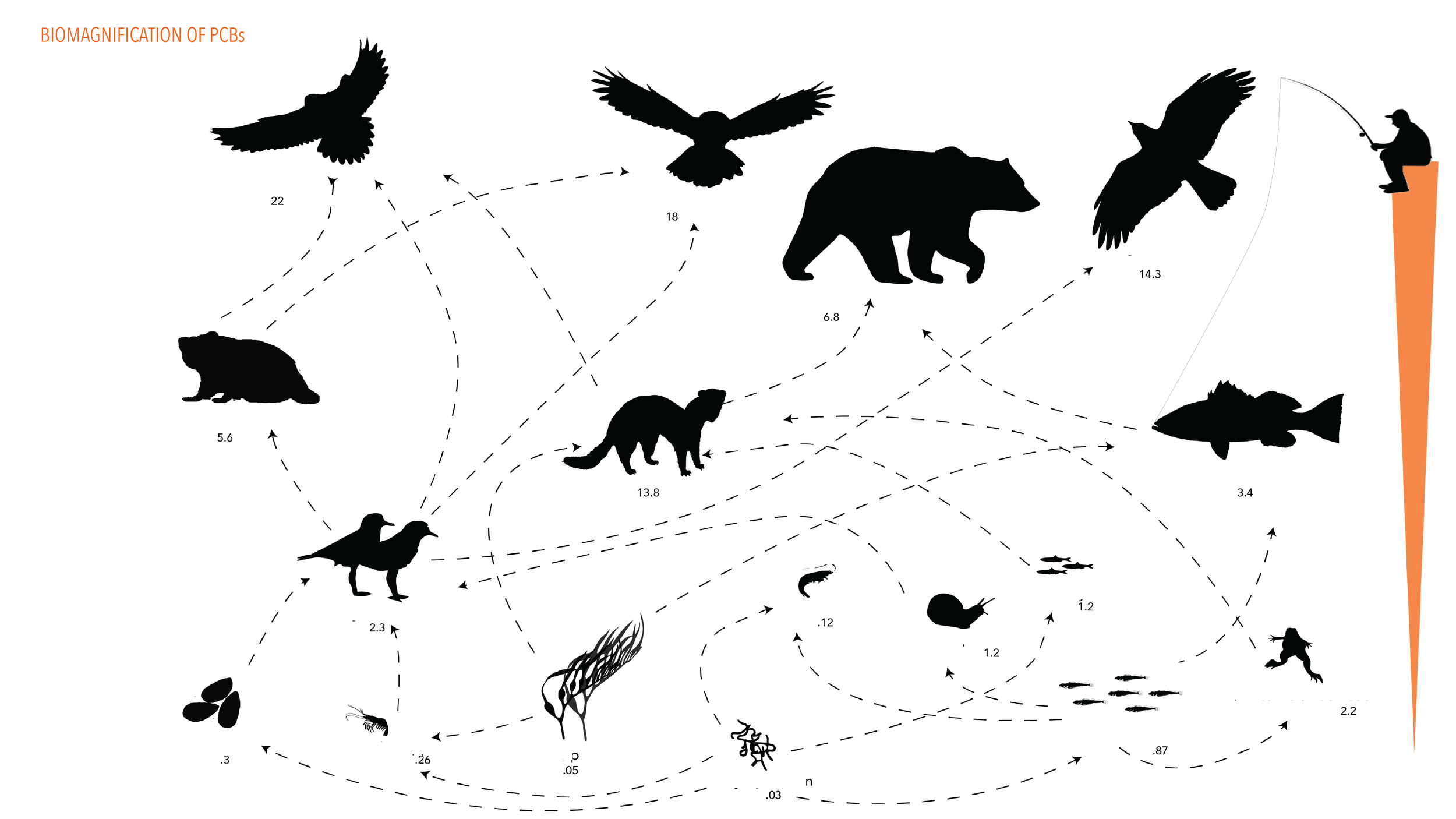

These heavier PCB blends are especially hydrophobic, meaning that today, the water column of the Housatonic River is largely uncontaminated. Although sorbed PCBs resist migration into the water fraction, PCBs enter food webs by ingestion and desorption in benthic microorganisms. [Figure 7] Initiated with these macroinvertebrates, PCBs biomagnify upward through the food chain, leading to highly toxic PCB levels in fish, birds, and potentially humans, where PCBs can be magnified up to 25 million times.5 [Figure 6]

Hundreds, maybe thousands of studies have identified associations between exposure to Arocolor 1254 and 1260 and adverse immunological, reproductive and dermatological effects and cancer. For example, PCBs are widely accepted as carcinogens among laboratory rats.6 However, as GE and Monsanto have maintained since the 1930s, effects in laboratory specimens do not necessarily correlate to human beings. Indeed human studies have been difficult to due PCBs slow speed of metabolism; human studies are challenged by: “limited exposure data, inconsistency among some results, and the presence of confounding factors.”7 These limitations make it impossible to use them for the basis of quantitative risk estimations. Thus, while science demonstrates a consensus in its concern about PCB toxicity, it also concedes that “ at present, levels of background PCB exposure evidence that adverse effects are occurring as a consequence of that exposure is not strong.”8 Without a smoking gun to prove human health effects, assessments made about the risks associated with PCB exposure are extremely diverse, contrary, and often obscured by politically-motivated agendas.

Without precise measurements, one if forced to speculate upon the magnitude of a given risk as compared to others risks. A translation process is required: a levying of judgment and prudence in the extrapolation of partial data. In Biocidal: Confronting the Poisonous Legacy of PCBs, Ted Dracos suggests that the analytical shortcomings of the biological sciences are overcome by the “weight-of-evidence principle.” He suggests: “If there are enough studies that link a substance such as PCBs to negative health effects or ecological damage, then the substance can be thought of scientifically as a toxin—regardless of a lack of proof in a single study.”9 Herein lies the challenge of assessing risks related to PCBs: they are impossible to quantify, leading to sharply divisive risk assessments among experts.

The issue of PCB volatilization exemplifies the complexity and controversy that surrounds PCB data. Today, “PCBs predominantly are redistributed from one environmental compartment to another.”10 We know that PCBs are globally circulated and are present in all environmental media, including human beings. (Most humans have a mean average of approximately one part per million of PCBs somewhere in their tissues.11) We also know that the major source of PCB release to the atmosphere (2 million pounds/ year) is the redistribution of the compounds that are already present in soil and water. However, our understanding of the processes and mechanisms of PCB volatilization remains incomplete: “the sorption adsorption/desorption of organic chemicals to natural particles are not completely understood.”12

The science of PCB volatilization has been imposed upon arguments to opposite ends. Some have coopted volatilization data to argue against environmental dredging, i.e. the risk of volatilization outweighs the benefits of removal. Others point to the volatility of PCBs in order to argue for the urgent removal of contaminated sediment from sensitive ecosystems, i.e. any risk of volatilization necessitates both the immediate removal of contaminated sediment and the immediate shipment of that sediment as far away as possible. So how does one negotiate through these contradictions when the health of a river ecosystem is at stake? This paper, strives to balance a conservative analysis of risk with the desire to take effective measures toward managing a healthy river.

In terms of PCB volatility, I assess the risk as moderate. This is to say that the risk is substantial enough to warrant mitigation strategies but not enough to outweigh the benefit derived from remediation operations. The highest risk of volatilization occurs during dredging, staging, treatment, and transportation, when contaminated sediment is disrupted, potentially off-gassing or re-distributing PCBs great distances as a result of current and wind. Studies like Harner et al. 1995 reveal that “soil and sediment served as a source of PCBs to the atmosphere instead of a sink as previously thought.”13 At minimum we know that the PCB exposure occurs through multiple processes of transfer. However, the PCBs in the Housatonic are relatively stable. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services writes: “biphenyls with 0–1 chlorine atom remain in the atmosphere, those with 1–4 chlorines gradually migrate toward polar latitudes in a series of volatilization/deposition cycles, those with 4–8 chlorines remain in mid-latitudes, and those with 8–9 chlorines remain close to the source of contamination.”14 Since Arocolor 1254 and 1260 contain at minimum five chlorine atoms, they are perhaps less likely to volatilize when contained in sediment.

The relative stability of Arocolor 1254 and 1260 also means that capping and disposal technologies are especially effective in minimizing volatilization. As I discuss later, there is always a risk associated with capping, however multiple sediment containment technologies go a long way to minimize this risk. Further, we must remember that PCB volatilization poses more than a local risk. After volatilization, PCBs precipitate out of the rain and accumulate in freshwater systems. Once certain concentrations are reached, PCBs off-gas back into the atmosphere, a cycle that leads to all the bodies of water on our planet to become thoroughly, and relatively evenly, polluted with PCBs.15 Thus, global contamination increases regardless of where hazardous waste is stored, and any measurement of ecological impact must consider the global context of PCB transfer.

Herein, while I cannot accurately quantify the risk of PCB volatilization, I strive to define the variables associated with its risk, categorize its magnitude, and specify target technologies to mitigate this risk. This kind of cost-benefit proposition typifies the evaluation of remediation strategies that follow in this text. I divide my evaluation of ‘Rest of River’ proposals into three parts: dredging, in situ capping, and disposal. In all three evaluations, I am guided by the weight-of-evidence principle, and I strive to be transparent when speculating with the hope of allowing the reader to levy his or her own judgement.

I will begin by evaluating dredging proposals, arguing that aggressive strategies for removing PCB contaminants must be tempered by efforts to protect the sensitive fluvial ecologies surrounding dredging locations. The development of various capping technologies offers the potential for reduced ecological impact, which I explore in the second section. Third, I will evaluate the controversy surrounding how to sequester and store contaminated sediment. Here, I will make the case for keeping contaminated sediment on-site, arguing that dollars assigned to the transport of PCBs out-of-state need to be re-appropriated to interventions that more comprehensively target the management of a healthy fluvial ecology.

Notes:

—2 “Consent Decree.” United States of America, State of Connecticut, Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. General Electric Co. Civil Actions No. 99-30225. October 2016.

—3 Gay, Frederick B. & Frimpter, Michael H. Distribution of Polychlorinated Biphenyls in the Housatonic River and Adjacent Aquifer, Massachusetts. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2266. US Government Printing Office: 1985. p.6

—4 Dracos, Ted. Biocidal: Confronting the Poisonous Legacy of PCBs. Boston: Beacon Press, 2010. p. 53

—5 Colburn, Theo. Our Stolen Future: Are We Threatening Our Fertility, Intelligence, and Survival?—A Scientific Detective Story. New York: Dutton, 1996. p.27

—6 Ludewig, G. “Cancer Initiation by PCBs.” PCBs: Recent Advances in Environmental, Toxicology, and Health Effects. University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, 2015.

—7 World Health Organization. Polychlorinated Biphenyls: Human Health Aspects. Geneva: World HealthOrganization, 2003. (Concise International Assessment Document; no. 55) 35

—8 Longnecker, Matthew P. “Endocrine and Other Human Health Effects of Environmental and Dietary Exposure to Polychlorinated Bophenyls.” PCBs: Recent Advances in Environmental, Toxicology, and Health Effects. University Press of Kentucky: Lexington, 2015.

—9 Colburn, p. 81

—10 https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp17.pdf

—11 Dracos, p. 53

—12 Pignatello, Joseph J. & Xing, Baoshan. “Mechanisms of Slow Sorption of Organic Chemicals to Natural Particles”. Environmetnal Science Technology, 1995, 30 (1).

—13 “CB Volatilization from Sediments.” Journal of Environmental Engineering, January 2006, Vol.132(1), pp.102-111 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

—14 https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp17.pdf

—15 Dracos, p. 50

Fig 5.

Sediment–water interactions behind dams create zones of contaminant retention and re-mobilization, where PCBs stored in fine sediments are periodically released into the water column through resuspension, diffusion, and hydrologic disturbance.

Fig 6.

PCBs biomagnify through the aquatic food web, accumulating in increasing concentrations from benthic invertebrates to fish and higher trophic predators, resulting in elevated exposure risks for wildlife and human communities reliant on the river ecosystem.

Fig 7.

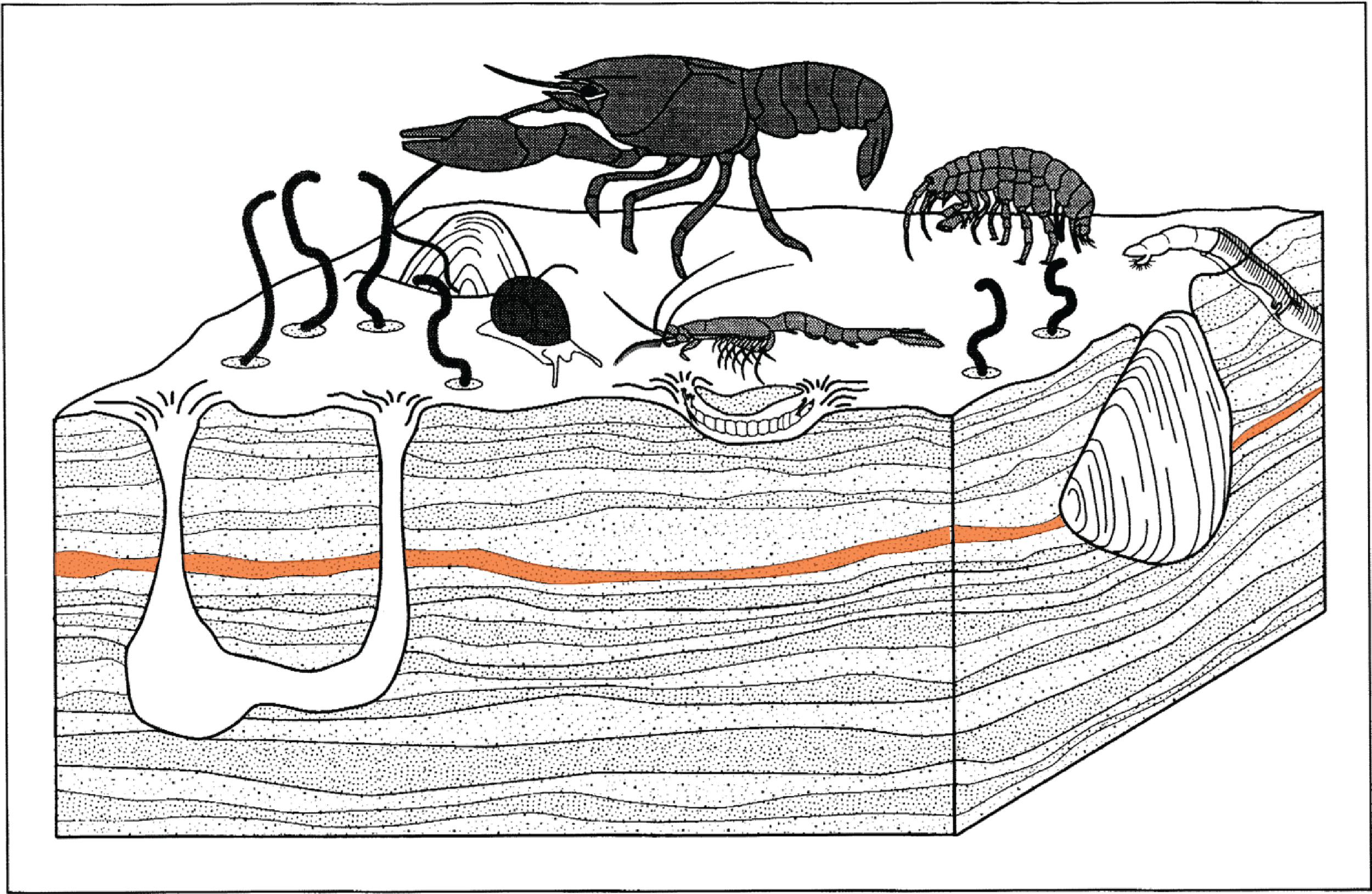

Although sorbed PCBs resist migration into the water fraction, PCBs enter food webs by ingestion and desorption in benthic microorganisms.

Fig 8.

The Housatonic River flows through a dolomitic bedrock formation characterized by carbonate-rich geology, which influences sediment composition, groundwater exchange, and the transport and persistence of contaminants within the river system.

3. Dredging

In the U.S. excavation and dredging have been the preferred methods for remediation of contaminated sediment, “having been used at more than 100 Superfund sites.”16 It is the persistence of PCBs that pushes dredging/removal/extraction technologies to the forefront of ‘Rest of River’ remediation proposals. Lower-impact bioremediation technologies (such as microbial degradation) are still in early stages of development and face challenges in processing highly-chlorinated PCBs like Arocolor 1254 and 1260. Thus, the predominant treatment for PCBs in sediments is dredging. Dredging involves the use of dredges to dislodge sediment from the channel bed and subsequently removingit from the bed to the surface.

Indeed, dredging is highly effective in removing PCBs. Most residual contaminant data indicate that contaminant concentrations are usually reduced by more than 85%.17 As compared to capping (discussed in the next section), dredging and excavation strategies permanently reduce the volume, toxicity, and mobility of PCBs. Remediation strategies with permanence are especially favored by the EPA. However, many argue that dredging is “environmentally disruptive and unsustainable.”18 Indeed the ecological ramifications of digging a river apart, removing contaminated sediment, and replacing it with clean sediment prove difficult to measure and predict.

The threat of environmental destruction is the most typical argument levied against dredging as a remediation strategy. GE’s proposal for “Monitored Natural Recovery (MNR),” a risk reduction approach that uses ongoing, naturally occurring processes to reduce the bioavailability of PCB contaminants in sediment, argues against dredging altogether. GE postures that the disadvantageous outcomes (ecological harm caused by dredging) outweighs the advantageous outcomes (the ecological benefit associated with decreasing PCB levels). GE campaigned its MNR proposal with the slogan “let’s not destroy the river in order to clean it.”

In order to evaluate this cost-benefit analysis, we must make a series of ecological impact assessments. First we must assess the success of a potential dredging operation at reducing PCBs. Upstream data forecasts positive outcomes downstream: studying the 1.5 mile section of river that has already been dredged in Pittsfield, dredging operations reduced PCB concentrations by over 99% since 2000.19 Second, in terms of the potentially negative impacts incurred by sediment removal, a 2012 report takes measure of the ecological benefit that can quickly result following the removal of PCBs: the 2012 Macroinvertebrate Sampling Report shows “the 2012 macroinvertebrate tissue sampling results show an overall reduction in PCB concentrations from 2007 - by an average of 9.4% in wet-weight concentrations and an average of 46.4% in lipid-normalized concentrations.”20

This compelling data makes a strong case in support of dredging. First, it shows the effectiveness of dredging in reducing PCB levels. Second, it demonstrates that certain macroinvertebrates rebounded quickly… in just five years after sediment removal was complete. This study argues against the central premise of GE’s MNR remediation strategy and its apocalyptic portrait of a post-dredged river landscape. However, can this encouraging data be correlated to ecosystem rebound at a larger scale? Since PCBs bioaccumulate upwards through the food chain, the decrease in PCB levels in macroinvertebrates suggests that we might see an even sharper decrease in the PCB levels of fish, birds, and mammals. However, while this study suggests that certain benthic microorganisms rebounded quickly, what can we speculate about greater species biodiversity following dredging?

One study in Poland suggests that dredging can actually increase biodiversity, showing “that Heteroptera abundance increased after dredging as a result of the emergence of pioneer species.”21 Still, there is no question that dredging is ecologically invasive, demanding that the river be largely dismantled in order to clean it. Biotic communities may be significantly disturbed or even completely erased during environmental dredging operations.22 In Contaminated Rivers: A Geomorphological-Geochemical Approach to Site Assessment and Remediation, Jerry Miller argues that “it is unlikely that rehabilitation or reconstruction of the site will be able to completely return a(dredged) area to its previous condition.” 23

The ‘functional lift’ diagram [Figure 7] describes the interrelated layers upon which river ecology performance is expressed. Environmental dredging has significant effects on river geomorphology, as dredging demands dismantling and recreating stream beds, channel flows, river banks, and riparian composition. The removal of contaminated sediment followed by river reconstruction, drastically changes the river’s functional lift: the river’s sediment transport capacity, substrate distributions, percentages of riffles and pools are all impacted. This leads to physiochemical and biological changes, which in turn effect hydrological and hydraulic changes downstream. The 2012 Macroinvertebrate Sampling Report demonstrates the capacity for certain species to adapt to a newly-dredged river, but it becomes extremely difficult to predict the ecological impacts following a profound altering of a river’s functional lift. As GE warns, “Habitats will be disrupted, populations will be displaced, and there is no way to know what will replace them.”24

In addition, contaminant resuspension presents a substantial risk to dredging operations. Environmental dredging must carefully mitigate related processes such as resuspension, release, and residuals… each posing variable risks for PCB re-exposure. Figure x shows the EPA’s PCB level test results in Rising Pond. This diagram shows that in certain areas, high contamination levels exist 4.5 inches deep or greater. Dredging carries especially high risks for leaving residual contamination if the contaminants exist in deeper sediments. “Existing data demonstrate that lower residual contaminations may be expected when contaminated sediment is located at the surface and can be removed during an initial pass.”25 Dredging threatens to re-expose contaminants that are currently cut off from the environment.

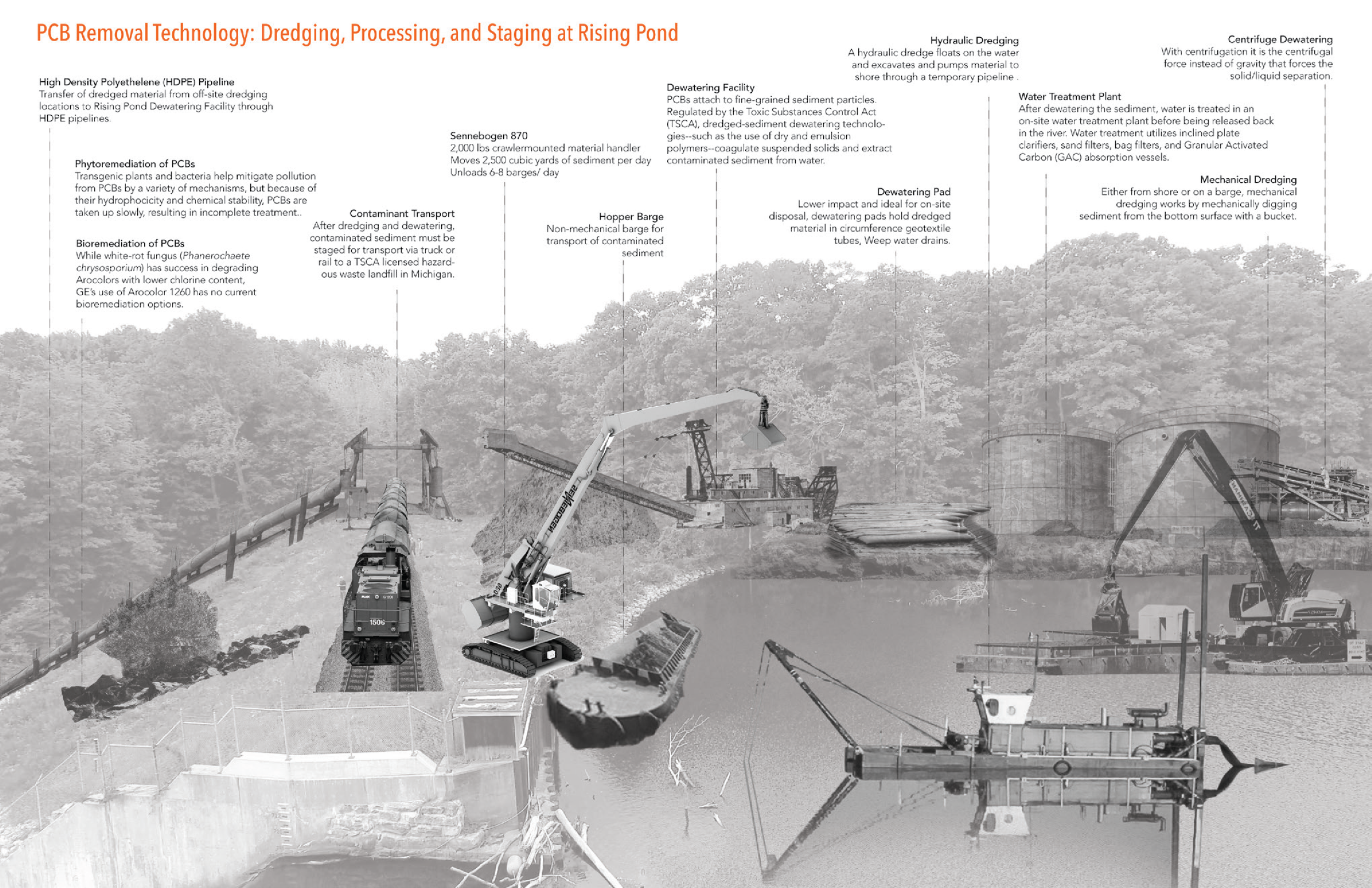

The choice of an appropriate dredge as well as the use of containment barriers (sheet-pile walls, silt curtains, silt screens) both function to limit the magnitude of PCB dredges utilize some form of bucket suspended on a cable or arm that scoops-up sediment. With mechanical dredging, less water is captured in the removed slurry, this reducing costs of treatment.

Mechanical dredging is mostly used when the volume of sediment to be removed is small, like in isolated sections of the Housatonic River, where space for staging is limited. In larger impoundment areas like Wood’s Pond or Rising Pond, hydraulic dredging is likely preferable. Hydraulic dredges dislodge contaminated material from the bed using rotating blades, augers, or high-pressure water jets, and then transports this slurry to the staging area through a pipeline. “Hydraulic dredges are most commonly used when large volumes of sediment must be removed, when a sediment handling facility is within piping distance, and where a pipe can be constructed without obstructing transportation on the water.”27

Beyond the direct impacts associated with sediment removal, dredging projects risk environmental impact from staging and treatment infrastructure. “Components of a removal remedy include sediment removal, transport, staging, treatment (both pretreatment and treatment of water and sediment, as necessary) and disposal (liquids and solids).”28 Once removed from the river bed, sediment is transported to treatment facilities. The proposed thirteen-year ‘Rest of River’ dredging operation would require establishing staging infrastructure on undeveloped land that currently supports wildlife habitat, extensively in certain areas. As GE warns, “the broad swath of largely contiguous forest will be fragmented by man-made access roads and staging areas.”29 [Figure 9]

Notes:

—16. Miller, Jerry R. Contaminated Rivers: A Geomorphological-Geochemical Approach to Site Assessment and Remediation. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007. p. 289

—17. Ibid, 297

—18. Sowers, Kevin R. & May, Harold, D. “In situ treatment of PCBs by anaerobic microbial dechlorination in aquatic sediment: are we there yet?” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2013, 24: 482-488

—19. GE-Pittsfield/Housatonic River Site 1.5-Mile Reach of Housatonic River (GECD820) 2012 Aquatic Macroinvertebrate Sampling Report” sent by GE to EPA on October 24, 2012.

—20. Ibid

—21. The Effect of Dredging of a Small Lowland River on Aquatic Heteroptera 2016, Vol.53(34), p.139-153 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

—22. Miller, p. 289

—23. Ibid, p. 301

—24 General Electric Company. Housatonic River - Rest of River Revised Corrective Measures Study Report. October 2010.

—25. Miller, p. 299

—26. Ibid, p. 299

—27. Ibid, p. 296

—28. Reible, Danny D. Ed. Processes, Assessment and Remediation of Contaminated Sediments. (Springer: New York, 2014) 368

—29. General Electric Company. Housatonic River - Rest of River Revised Corrective Measures Study Report. October 2010.

Fig 9.

Mechanical dredging removes contaminated sediments through physical excavation using clamshell buckets or similar equipment, disturbing the riverbed and resuspending fine particles, which can increase short-term turbidity and mobilize contaminants during removal operations.

Fig 10.

Functional lift refers to the measurable improvement of ecological processes and system performance resulting from an intervention, such as enhanced habitat quality, increased biological productivity, or improved nutrient and contaminant cycling within a restored river system.

Fig 12.

PCB dredging technology combines mechanical sediment removal with on-site processing and staging, where excavated materials are dewatered, stabilized, and temporarily stored before transport and disposal, creating a complex remediation infrastructure that extends contamination management beyond the river itself.

Fig 13.

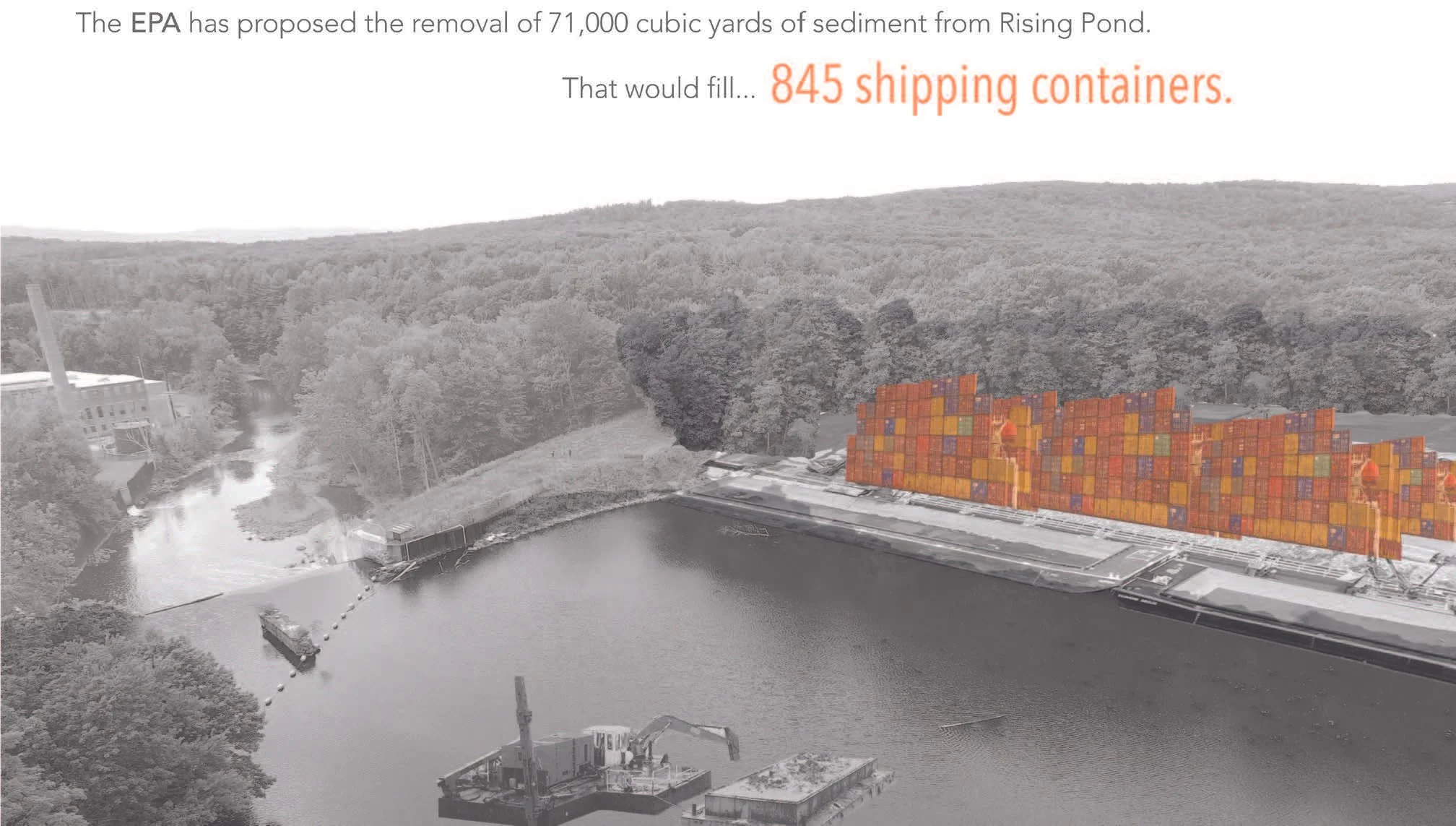

The EPA has proposed the removal of 71,000 cubic yards of sediment from Rising Pond. That would fill 845 shipping containers.

4. In Situ Capping

The EPA does not mandate specific remediation technologies for GE to use in cleaning the river. Instead, as seen in its 1999 “Consent Decree,” the EPA identifies PCB hotspots between Pittsfield and Great Barrington. In these hotspots, GE is required to remediate surficial soils that “a total PCB concentration equal to 1% of the existing average” is achieved.30 This allows GE to design unique dredging and capping strategies for each averaging area so long as the spatially-weighted total PCB level drops to 1% of existing levels.

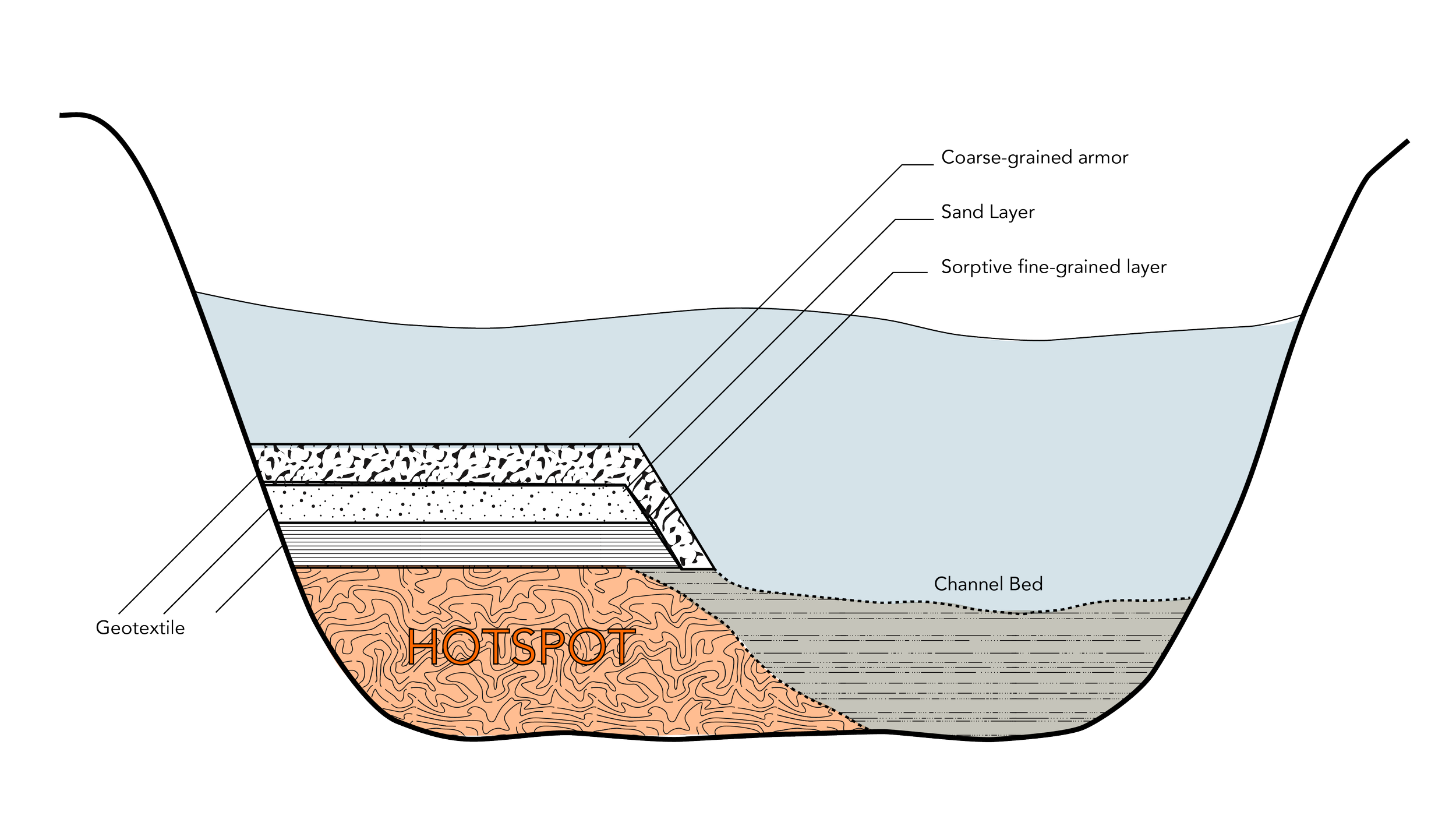

Offering a less invasive alternative to dredging, capping involves isolating a contaminated sediment bed with a clean layer of sediment, commonly consisting of sand, gravel, silt, or crushed rock debris.31 In the case of a passive cap, this sediment layer simply forms a physical barrier between contaminants and the aquatic environment, cutting down the bioavailability of contaminants. Thoms et al. (1995) summarized 240 observations of bioturbation mixing depths in fresh and salt water involving a wide variety of sediment dwelling organisms and found that more than 90% were 15 cm or less, and more than 80% were 10 cm or less.32 This suggests that even a relatively thin capping layer can effectively eliminate bioturbation, the mixing associated with benthic organisms.

A significant debate exists with regard to the efficiency and risk of capping technologies. Eek et al. (2008) used a laboratory microcosm to demonstrate that the flux of PCB is reduced by 99% when using a 10 cm capping layer.33 GE applies this optimistic data to Wood’s Pond in Lenox Dale, arguing that an engineered cap achieves equal ecological protection to that of sediment removal. (It is likely, however, that GE will argue for any remediation strategy that significantly reduces its costs.) In fact, any risk assessment associated with capping is extremely difficult due to a “lack of longterm experience with capped deposits.”34 Capping toxic sediment in estuarine waters has only been practiced for the last forty years. In turn, many unanswered questions persist. Will PCBs migrate through capped material in the longterm? Will the structural integrity of the cap hold up during extreme storm and flood events? The EPA has been skeptical about the matter, arguing “that a cap could be compromised by a flood, dam breach or engineering failure.”35

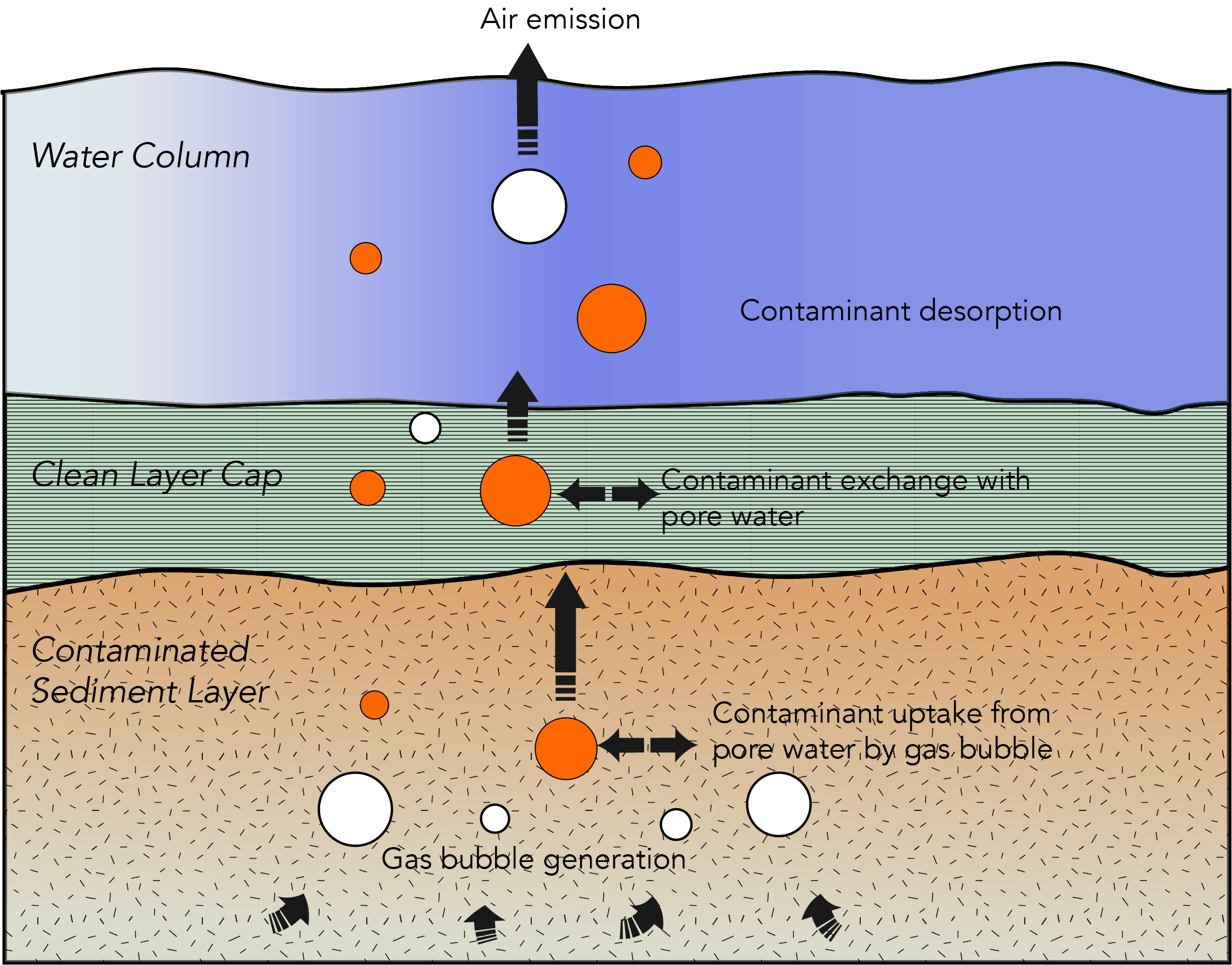

Cap failure is primarily driven by geomorphologic changes. Along highly dynamic rivers where scour and fill during floods is significant, the cap sediment may be eroded and transported downstream, while “deeper contaminated sediments may be brought to the surface.”36 In situ capping should be avoided if the river is likely to face disturbances in the near future due to land-use conditions or other disturbances in the watershed.37 Additionally, some raise concerns about groundwater seepage and gassing of PCBs through caps. Seepage is often a function of distance from shore with higher seepage rates along the shoreline or along river banks. Gases are often generated in sediments due to the degradation of organic matter.” These gases can transport volatile contaminants through partitioning into the gas phase and transport low volatility, hydrophobic contaminants through accumulation at the gas-water interface.”38

Thus, many regard capping as a short-sighted solution. “Passive capping limits exposure of PCBs to the food chain, but since PCBs remain in the environment a potential long-term risk owing to gradual or acute disruption of the cap remains.”39 Conversely, dig-and-dump strategies decrease risks for re-exposure. Primarily this is because a landfill employ liner and capping technologies that encase contaminants versus a partial horizontal cap. Second, hazardous waste landfills are sited in environments with more stability as compared to the flux of a river floodplain.

For many, the increased risk of contaminant re-exposure related to in situ capping settles the debate; sediment must be removed and landfilled. However, additional risk assessments begin to muddy the waters: consider contaminant resuspension. While dredging activities can remobilize contaminants into the water column, capping poses a decreased risk: two studies by the EPA in Washington and Massachusetts demonstrate that “contaminant resuspension, although substantially higher than observed in pre-capping events during both surveys, was relatively low for all capping events” and “dissipated to background levels in a mater of hours following cessation of capping activities.”40

The effectiveness of caps can be enhanced by active capping technologies. The most commonly used additives include apatite, activated carbon, clay mineral, zero-talent iron, zeolites, and various proprietary materials, such as AquarBlok. While passive caps contain PCB sediments, active caps treat PCB sediments: “a cap layer can be a biologically-active region where anaerobic processes and reductive biotransformations occur.” As contaminants migrate through the cap, “biotransformations can provide a method of treatment to prevent (or significantly delay) contaminant breakthrough to the BAZ at the cap-water interface.”41 These bioremediation technologies are utilized in landfill liner systems as well, and as discussed earlier, technologies still require development. However, while Arocolor 1254 and 1260 are difficult to destroy, certain active caps employ additives that immobilize them. One example is activated carbon, “which may provide enhanced immobilization by strongly partitioning PCB onto its surface.”42

In ecological magnitude, the impact of in situ cap failure is substantial. In highly dynamic river reaches, in situ capping is an inappropriate solution, although contamination is generally lower in these areas due to this very dynamism. However, in larger, more stable impoundments such as above dams—hotspots at the heart of ‘Rest of River’ proposals—multiple strategies involving in situ capping can provide highly effective PCB containment while also decreasing biological disruption.

In situ caps demand monitoring indefinitely, passing the management of contaminants onto future generations, and the costs related to contaminant monitoring and maintenance can be substantial. Conversely, sediment removal and disposal operations offer permanent solutions with GE paying all costs up front. This is unquestionably valid. However, the pursuit of sediment removal as the singular principle guiding river remediation is unsustainable. In looking for more sustainable solutions, in situ capping technologies (working in tandem with dredging technologies) offer a path toward sustainable PCB remediation. Indeed this sustainability comes with the burden of long-term monitoring and management. Is Berkshire County inclined to assume this burden?

Notes:

—30. “Consent Decree.” United States of America, State of Connecticut, Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. General Electric Co. Civil Actions No. 99-30225. October 2016.

—31. Gomes, Helena I. et all. “Overview of in situ and ex situ remediation technologies for PCB-contaminated soils and sediments and obstacles for full-scale application.” Science of the Total Environment 445–446 (2013) 237–260

—32. Reible, Danny. “In Situ Sediment Remediation Through Capping: Status and Research Needs.” Department of Civil Engineering, University of Texas Austin.

—33. Gomes, p.251

—34. Keillor, Philip. Deciding About Sediment Removal: http://aqua.wisc.edu/publications/PDFs/SedimentRemediation.pdf

—35. Garver, , Ben. “GE: ‘No Environmental Benefit’ to PCB Disposal Outside Berkshires.” The Berkshire Eagle. 2 April 2017. Print .

—36. Miller, Jerry R. Contaminated Rivers: A Geomorphological-Geochemical Approach to Site Assessment and Remediation. Dordrecht: Springer, 2007. p. 289

—37. Ibid, 339

—38. Reible, p. 369

—39. Sowers, Kevin R. & May, Harold, D. “In situ treatment of PCBs by anaerobic microbial dechlorination in aquatic sediment: are we there yet?” Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2013, 24: 482-488

—40. https://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo68868/ZyPDF.cgi.pdf

—41. Reible, p. 368

—42. Gomes, p. 251

Fig 14.

In situ capping carries risks associated with gas bubble migration, as biogenic or geochemical gas formation within underlying sediments can disrupt cap integrity, create preferential pathways, and facilitate the upward transport of PCBs into the overlying water column.

Fig 15.

The design of a multilayer in situ cap for PCB-contaminated sediments integrates reactive, isolation, and armor layers to limit contaminant flux, enhance chemical sequestration, and maintain long-term stability under hydraulic, biological, and geochemical stresses.

5. Disposal

Once sediment is removed, staged, and treated, the complicated issue of waste disposal emerges, and the persistence of Arocolor 1254 and 1260 comes back into play. Since these PCBs cannot be eliminated, they must be landfilled, and the question becomes where. For GE, it becomes advantageous to dispose of waste nearby. The three proposed landfills in Lenox Dale, Lee, and Housatonic represent affordable storage locations for GE due to their close proximity to points of extraction.

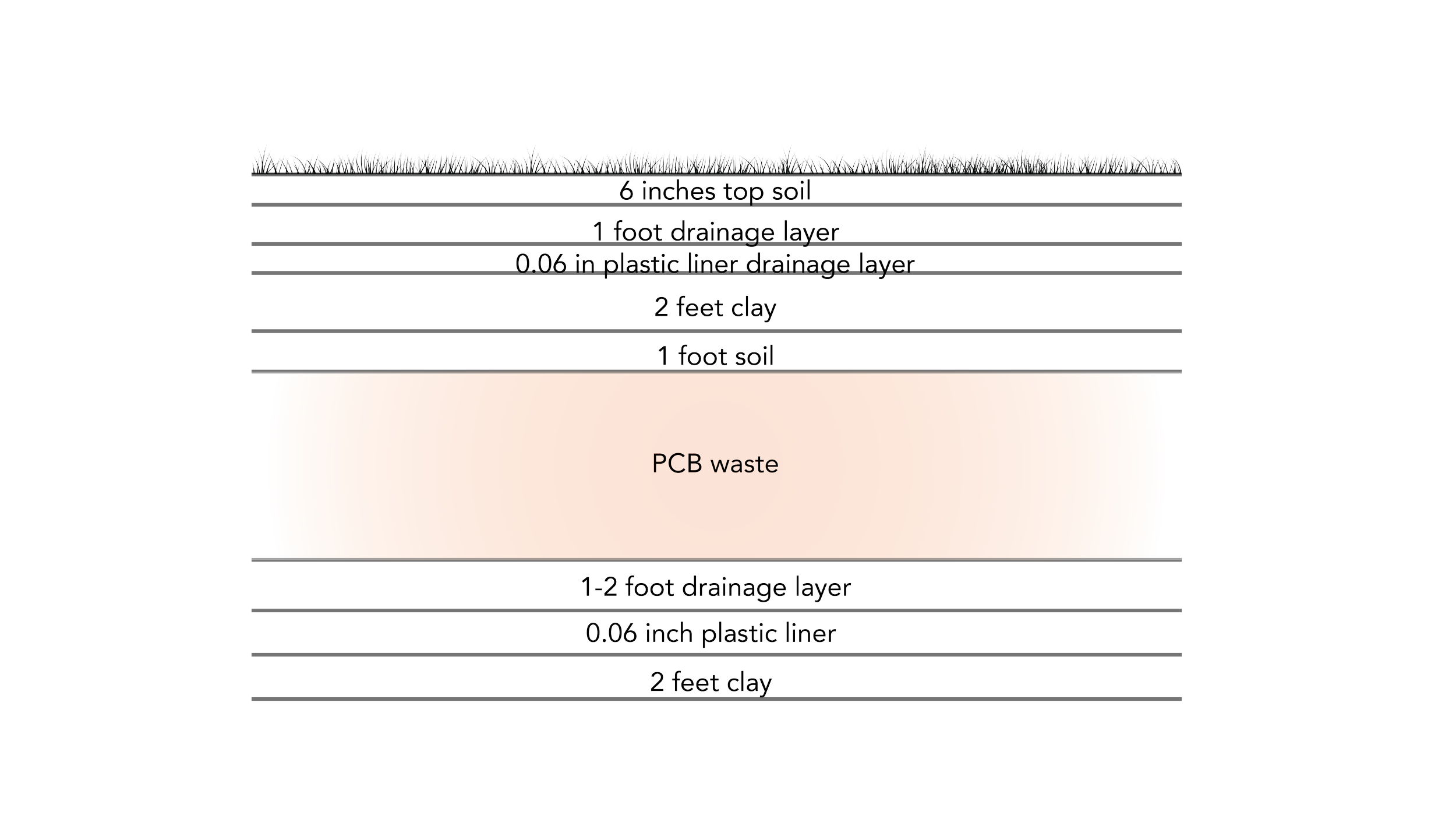

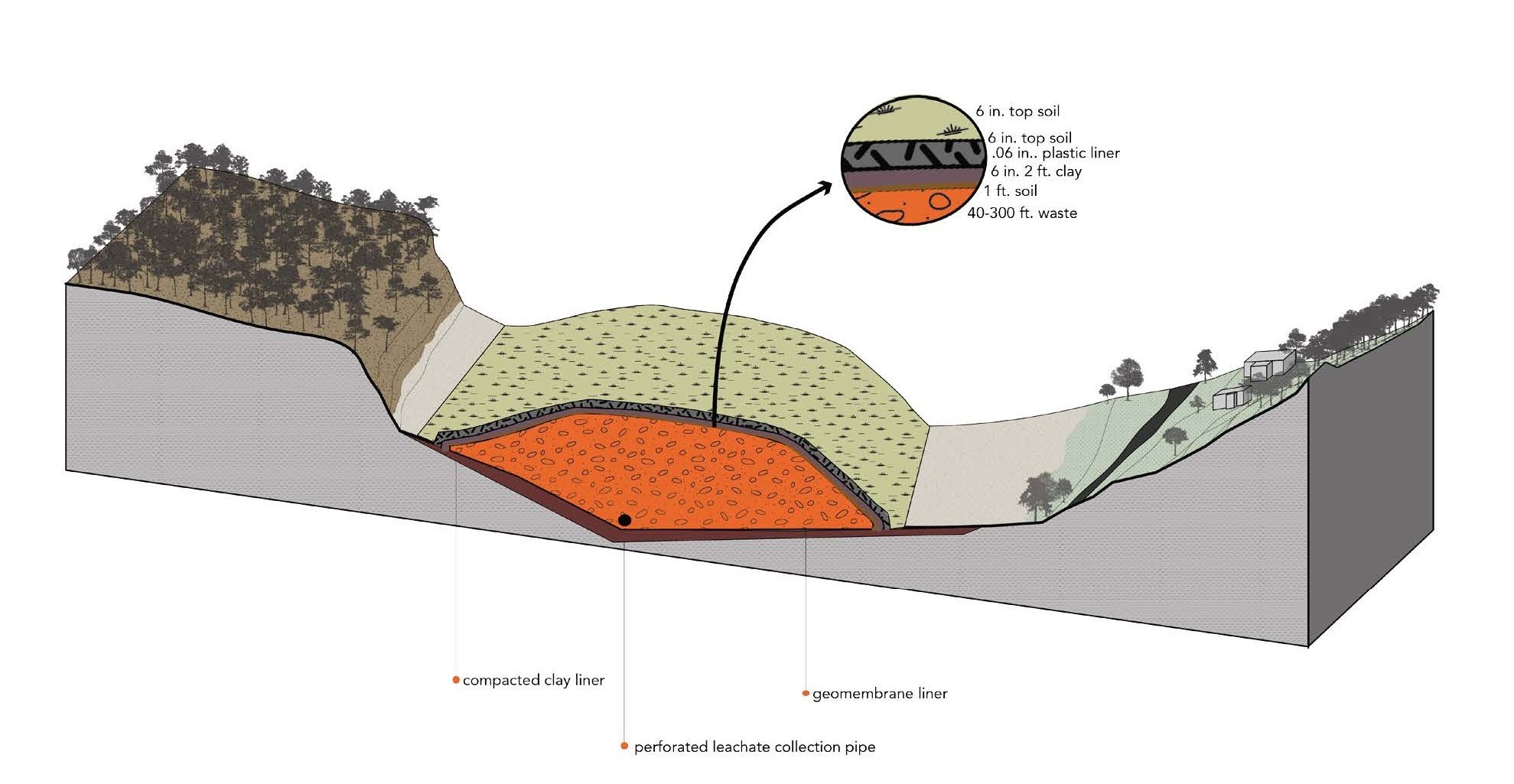

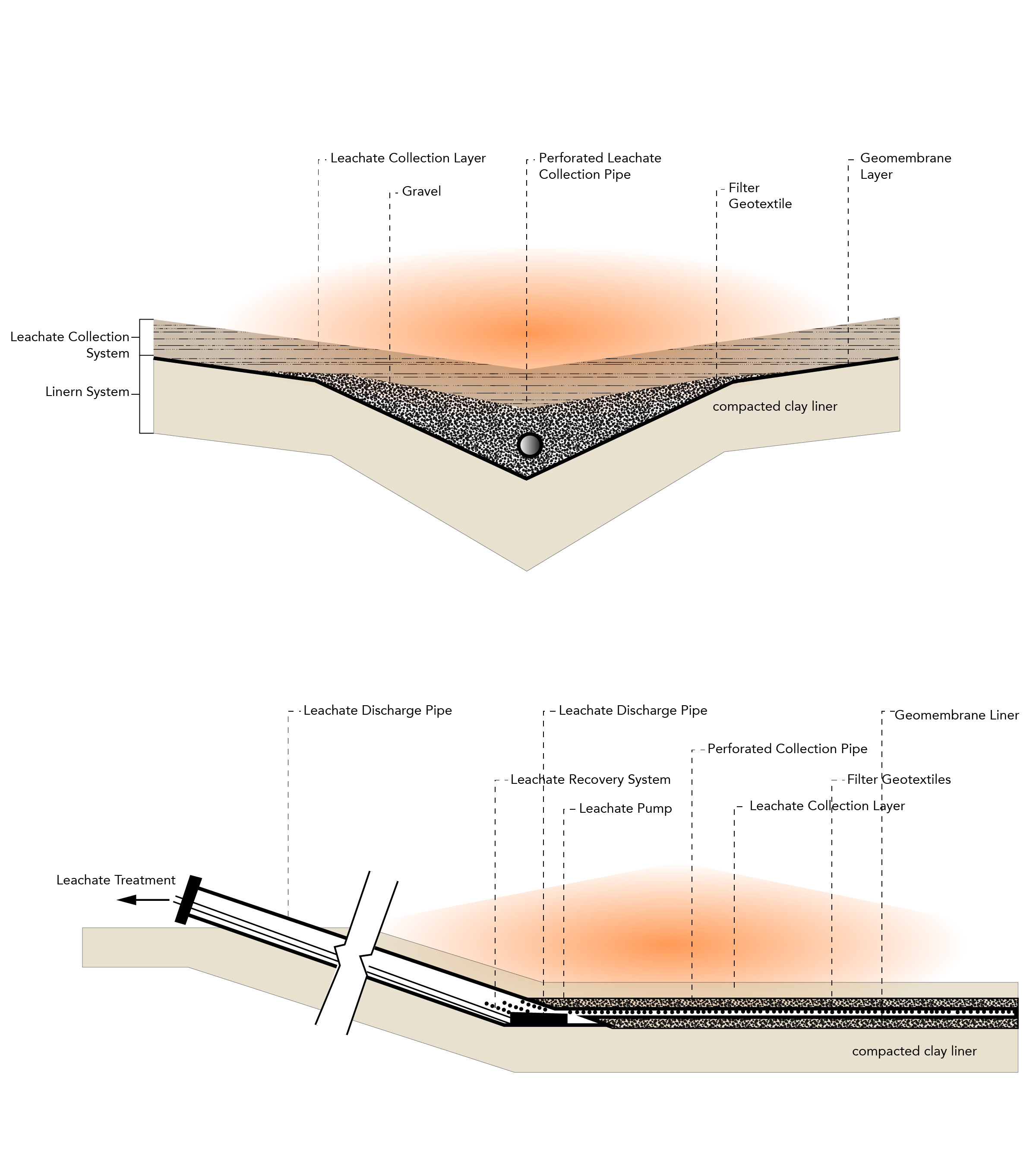

The US Department of Energy describes the criteria for a PCB storage facility: “(1) an adequate roof and walls, (2) a floor that minimizes penetration of PCBs, and (3) a 6-inch-high curb that provides a containment volume equal to at least twice the internal volume of the largest PCB Item or 25% of the total internal volume of all PCB Items stored in the facility.”43 Additionally, the facility must be located above the 100-year flood elevation and may not have any openings that would permit liquids to drain beyond the storage area. Liquid seepage must be collected and transmitted to a leachate collection system. A liner system prevents leachate migration, using layers of materials with various permeability. Geosynthetics such as synthetic polymers and geotextiles allow water to pass but not the fine sediment containing PCBs. Low permeability geomembranes form the outer layer protecting the environment from contamination.

There are always dangers of liner system failures, and again, technologies are too recent to quantify these risks. But the result of landfill failure surely has a lower impact due to the location above the floodplain, i.e. landfilling relocates contaminants to less fragile ecological zones. Additionally, compared to in situ capping, the risk of landfill failure is lessened by the stability of the site compared to a dynamic river. However, the only difference from in situ capping is the secondary liner system with leachate collection used in landfill design. Both strategies employ similar liner system technologies and work to the same end: to sequester PCBs away from ecological flows.

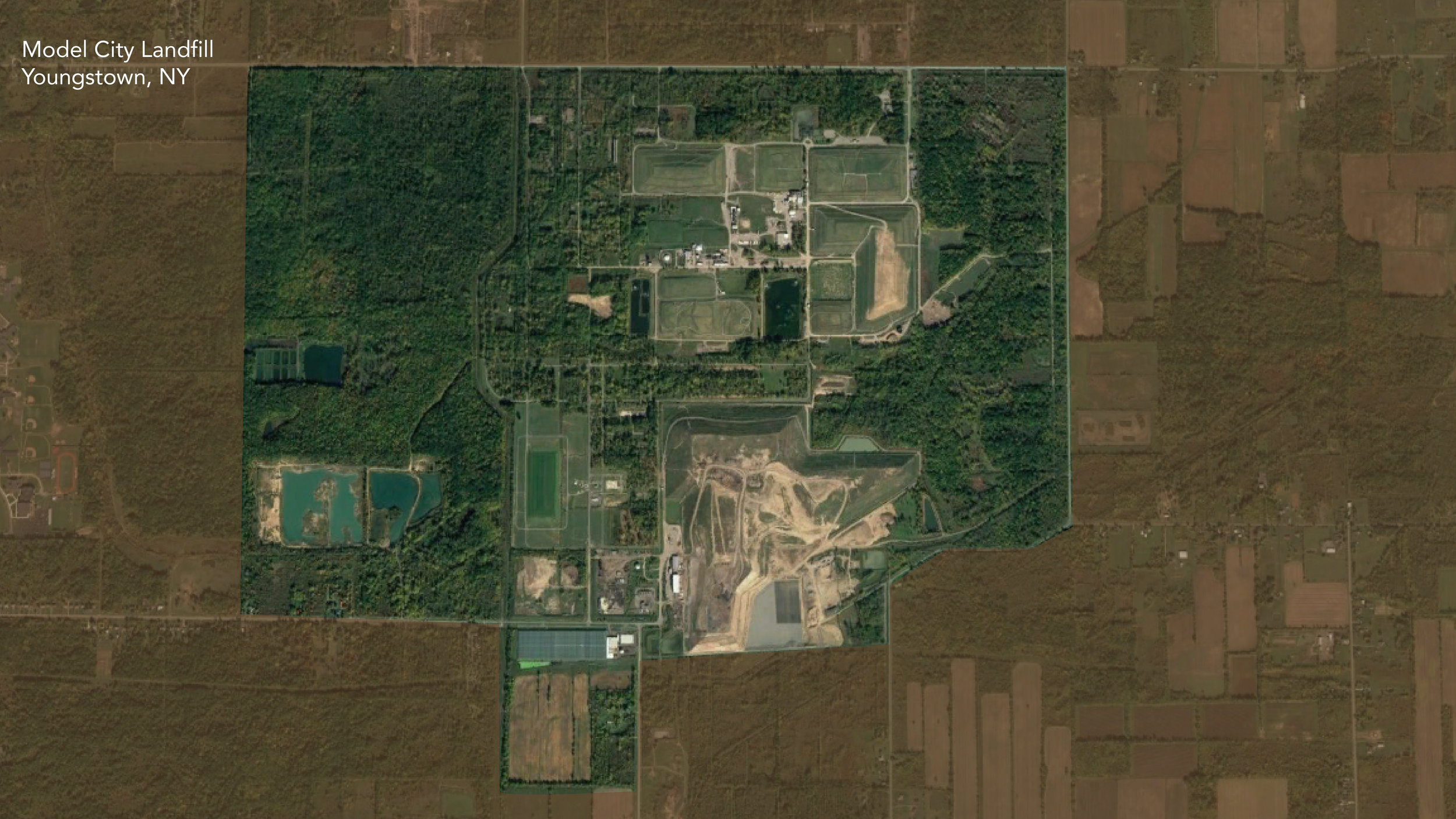

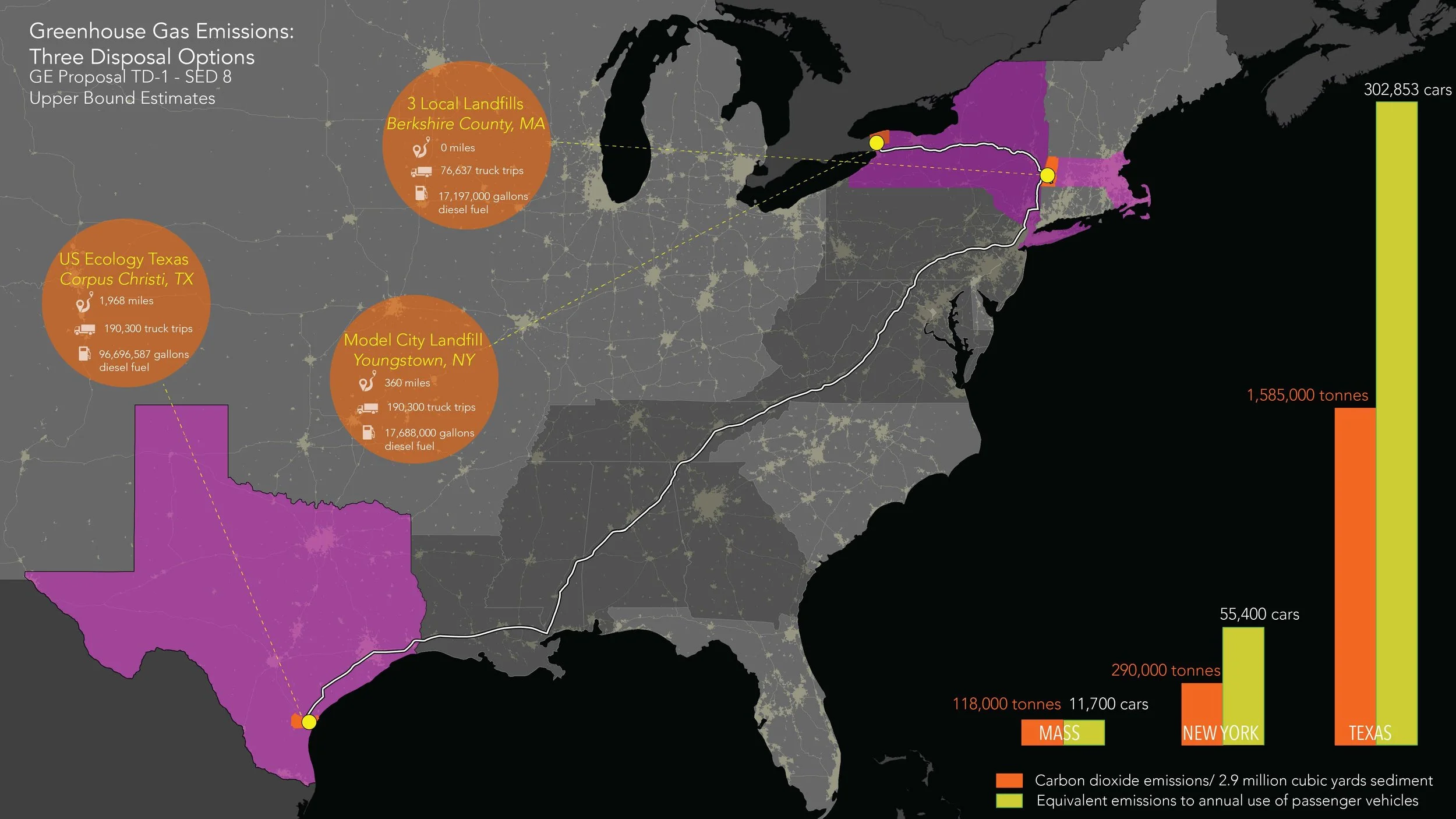

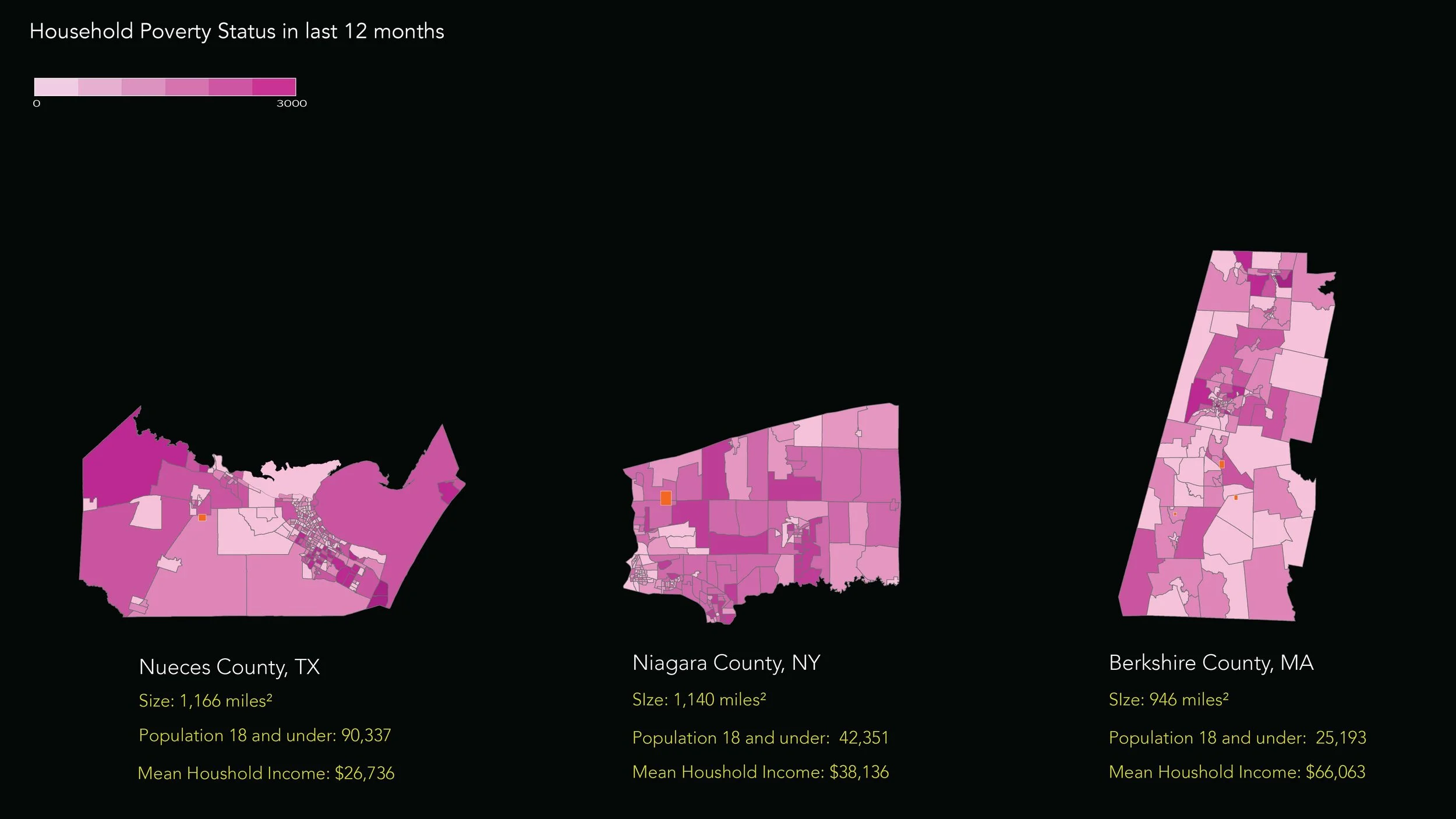

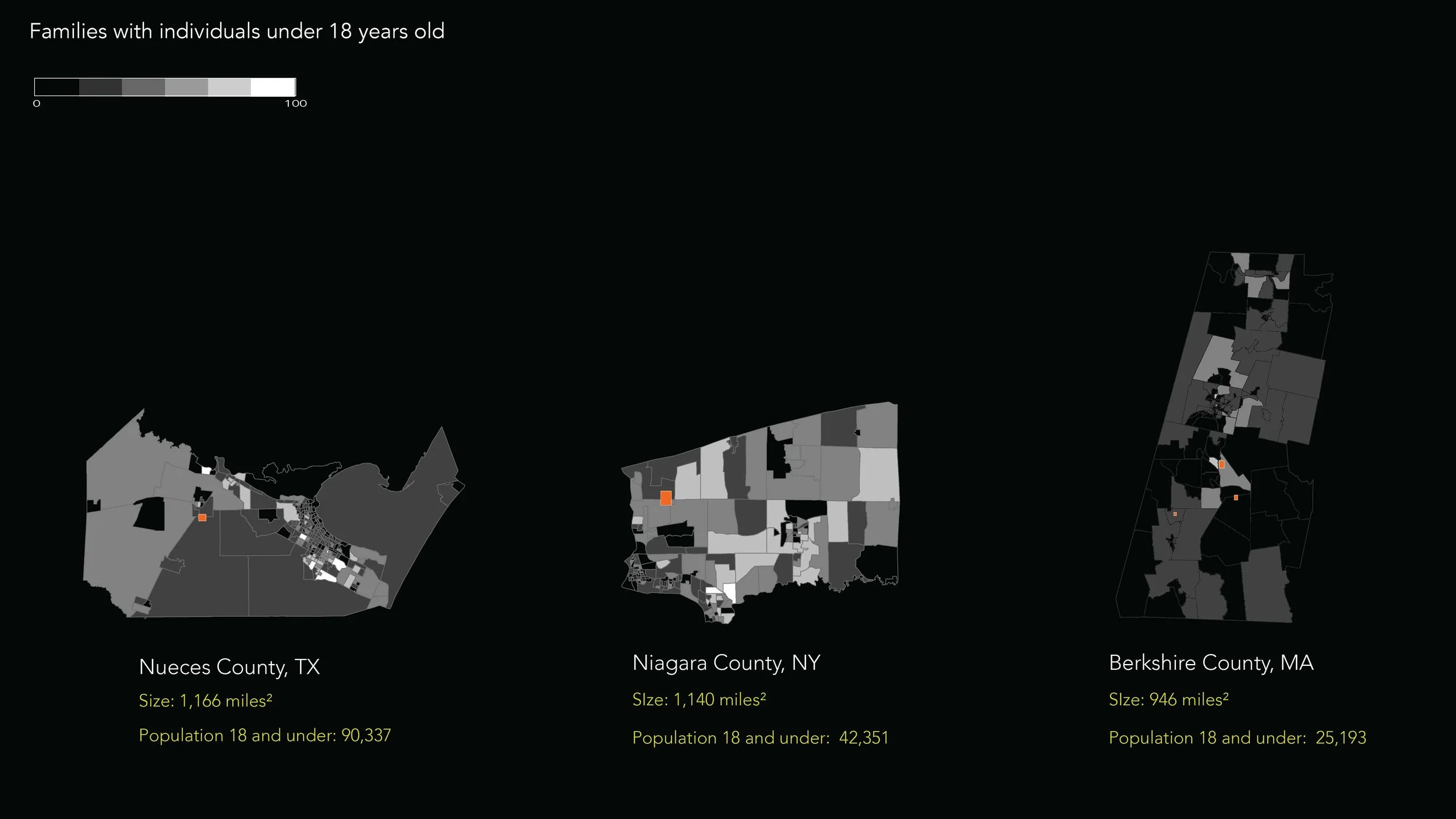

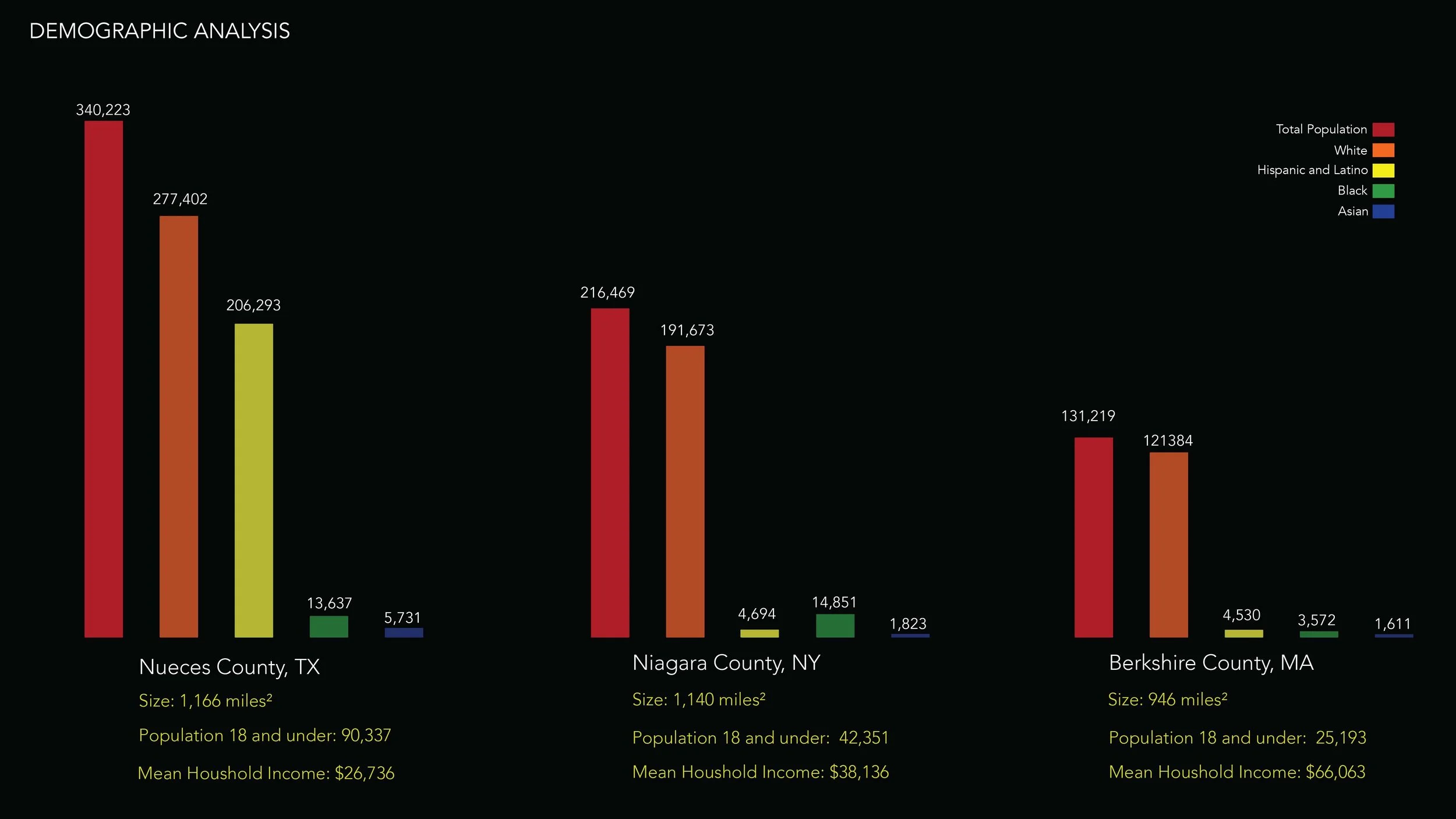

For many Berkshire resident, this sequestration needs to be sited as far away from the Berkshires as possible. Since GE has already polluted the river for nearly a century, why should the eleventh-ranked Fortune 500 company be allowed to save money and in turn pollute three new sites in Lee and Great Barrington? Local municipal leaders have been united in their position that contaminated sediment must be transported out-of-state, to a facility such as Model City Landfill in Youngstown, NY, or US Ecology Texas Inc. in Corpus Christi, Texas. The transport of waste for disposal to an out-of-state landfill would cost GE an additional $160 million to $245 million,44 but why should the 11th-ranked Fortune 500 company be spared a dime in cleaning up the Housatonic River?

Indeed, issues of contaminant disposal have multiple impacts across our cost-benefit equation. Certainly when measured in dollars, out-of-state transport comes at a huge cost. However, how can we measure the ecological impacts of out-of-state disposal? US Ecology Texas Inc. is a permitted RCRA hazardous waste facility, offering bulk PCB waste storage and promising that “long-term risks associated with disposal are minimized.”45 Many believe that only in these licensed landfills are regulators equipped to manage these persistent pollutants, arguing that until a time when technology is developed to degrade these PCBs, it behooves us to keep PCB toxins consolidated in licensed landfills far away from Berkshire County.

Therefore, we can assume that contaminants disposed of at US Ecology Texas Inc. have less risk for re-exposure to ecosystems than if they are stored in landfills in Berkshire County. (Certainly even in the case of landfill failure at US Ecology Texas, there exists no risk that those contaminants will reenter the Housatonic River.) However, the risk of PCB contamination exposure due to landfill failure is not the only ecological consideration. In fact, one could argue that the further the distance that contaminated sediment must travel from the riverbed, the greater the ecological disruption. As many as 243,000 truck trips traveling upwards of 142 million miles would be required to transport 2.9 million cubic yards of contaminants from Berkshire County to Corpus Christi. GE likes to point out that the transport of contaminated sediment would have a carbon footprint equal to the annual output of as many as 55,400 passenger vehicles.46

All accumulated, risk assessments related to sediment disposal speak to a complex cost-benefit scenario. Strictly measuring the risk of PCB re-exposure to the Housatonic River, the farther away from Berkshire County that sediment is stored, the better. However, this benefit to the Housatonic River at the county scale proves problematic at larger scales of analysis. For example, by one metric sediment stored at US Ecology Texas has a smaller risk of re-exposure due to it being a technologically-advanced, regulated facility. However by another metric, this lowered risk of re-exposure may not warrant the carbon footprint associated with moving 2.9 million cubic yards of sediment a distance of 2,000 miles. Geographic considerations don’t necessarily clarify the debate. The arid climate of East Texas might decrease the risk of landfill failure, but does the warmer climate in Corpus Christi increase the likelihood of PCB volatilization?

Even if we are certain that exposure risks are lower in Corpus Christi versus Berkshire County, does that warrant shifting the burden of that albeit smaller risk to a different, more vulnerable population? Corpus Christi is already engaged in an environmental justice controversy surrounding its “Refinery Row” district, a primarily low income, Black and Hispanic community facing air and ground pollution caused by adjacent industries.47 One could argue that this more disenfranchised population is less equipped to protect itself against the risks of hazardous waste disposal than are the more affluent communities in Berkshire County. Indeed PCB contaminated sediment must be disposed of somewhere, but how do issues of environmental justice potentially influence our cost-benefit equation? Moving contaminants beyond the river’s floodplain would have potentially zero ecological benefit, incur a substantial carbon footprint, and merely redistribute Housatonic waste upon a different community and ecosystem.

In considering the environmental justice issues associated with hazardous waste disposal, it is worth situating the Housatonic River’s PCB contamination in the context of global PCB pollution. According to the United Nations, approximately 1.2 million metric tons of PCBs were produced between 1929 and 1977. Today, approximately one third are now circulating in the environment.48 The worldwide project to contain PCB contaminants is a massive undertaking. The persistence of PCBs—the vast timespan that they will poison surrounding ecosytems—forces the issue of dredging to the forefront of remediation proposals, as these contaminants will continue to poison waterways for many generations if they are not cut off from food webs. However, the human health risk during any individual’s lifespan, while significant, is mild in comparison to the size of the problem of remediation, a project requiring a massive amount of manpower, technology, and time.

Notes:

—43. U.S. Department of Energy. Office of Environmental Guidance. “PCB Storage Requirements.” EH-231-060/1294 (December 1994).

—44. Garver, , Ben. “GE: ‘No Environmental Benefit’ to PCB Disposal Outside Berkshires.” The Berkshire Eagle. 2 April 2017. Print .

—45. https://www.usecology.com/Locations/All-Locations/US-Ecology-Texas.aspx

—46. General Electric Company. Housatonic River - Rest of River Revised Corrective Measures Study Report. October 2010.

—47. http://www.umich.edu/~snre492/mezza.html

—48. Dracos, Ted. Biocidal: Confronting the Poisonous Legacy of PCBs. Boston: Beacon Press, 2010. p. 51

Fig 16.

PCB landfill design relies on a layered containment system—including low-permeability liners, leachate collection and removal layers, drainage media, and engineered caps—to isolate toxic materials, prevent contaminant migration, and ensure long-term environmental protection.

Fig 17.

Landfill liner systems employ composite technologies—such as compacted clay layers, geomembranes, and geotextiles—to create low-permeability barriers that control leachate movement and prevent the migration of PCBs into surrounding soil and groundwater.

Fig 18.

Leachate collection systems use engineered drainage layers, perforated piping, and sumps to capture, convey, and remove contaminated fluids generated within landfills, reducing hydraulic pressure on liner systems and limiting the potential release of PCBs to surrounding environments.

Fig 19.

The proposed remediation plan involves transporting dredged PCB-contaminated sediments from the Housatonic River in western Massachusetts to the Model City Landfill in Niagara County, New York, extending the spatial footprint of contamination management by relocating hazardous waste from the river system to a long-term engineered disposal facility.

Fig 20.

An alternative disposal pathway directs PCB-contaminated sediments excavated from the Housatonic River in western Massachusetts to the US Ecology Texas Inc. facility in Andrews County, Texas, reframing river remediation as a transregional waste transport and containment operation.

Fig 21.

Transporting PCB-contaminated waste to out-of-state disposal facilities significantly increases greenhouse gas emissions, as long-distance hauling by truck or rail adds substantial carbon and energy costs to remediation efforts beyond those generated at the site itself.

Fig 22.

Remediation strategies that rely on shipping PCB-contaminated waste to out-of-state landfills must account for the human populations along transport corridors and near disposal sites, where communities bear added health, safety, and environmental risks associated with handling, transit, and long-term containment of hazardous materials.

Fig 23.

Remediation plans that ship PCB-contaminated sediments from the Housatonic River to the Model City Landfill in Niagara County, New York, and the US Ecology Texas Inc. facility in Andrews County, Texas, extend risk to distant human populations, particularly in counties with lower mean household incomes, raising environmental justice concerns about the unequal distribution of health, safety, and long-term contamination burdens.

Fig 24.

Shipping PCB-contaminated sediments from the Housatonic River to the Model City Landfill in Niagara County, New York, and the US Ecology Texas Inc. facility in Andrews County, Texas, relocates risk to regions with younger populations, where PCB exposure is especially hazardous to children, raising significant public health and environmental justice concerns.

Fig 25.

Transporting PCB-contaminated sediments from Berkshire County to proposed disposal sites in Niagara County, New York, and Andrews County, Texas, shifts environmental justice burdens onto communities with fewer economic and institutional resources than those available in Berkshire County, reinforcing inequities in risk, capacity, and long-term environmental protection.

6. Summary of Recommendations

I argue that any environmental dredging projects must prioritize sustainability. By emphasizing only the reduction of PCB levels in sediment, current 'Rest of River' proposals miss the forest for the trees. Granted, dig and dump strategies provide immediate results, greatly improving ecological function. However, if we contextualize the cleanup of the Housatonic-first within the larger goal of river stewardship and second within the global project of contaminant sequestration-we face a more complex, a more nuanced, and ultimately a more ambitious project. Instead of binary decisions surrounding dredging versus capping or local versus out-of-state proposals, Berkshire County needs to organize its own council of experts to find hybrid solutions to maximize the ecological, economic, and cultural value of the Housatonic River. Efforts to decrease PCBs in sediment (measured in PPM) must exist within a larger framework or fluvial system dynamics.

Certainly, the remediation of PCBs is the central problem, but there is no single remediation strategy to manage PCB contamination. "The successful remediation of a site will depend on proper selection, design and adjustment of the technology or combined technologies to the site characteristics. "49 In highly dynamic river reaches, in situ capping is an inappropriate solution. (Of course, contamination is generally lower in these areas due to this very dynamism.) But in the case of high contamination in these locations, proposals must consider low-impact ways to stage mechanical dredging operations, transporting sediment for treatment in nearby but off-site dewatering facilities. In larger, more stable impoundments such as above dams-hotspots at the heart of 'Rest of River' proposals-multiple strategies involving in situ capping can provide highly effective PCB containment while also decreasing biological disruption. Capping contaminated sediment in situ (versus transporting it off-site) certainly poses an increased risk for re-exposure, meanwhile carrying forward the necessity to monitor and manage each cap indefinitely. However, in terms of a larger scale environmental cost benefit equation, all PCBsediment must ultimately be capped somewhere: in situ, in local landfills, or in out-of-state facilities.

In turn, we can consider hybrid containment strategies that straddle dredging, capping, and disposal technologies. Hydraulic dredgers can pipe sediment to nearby locations for containment. Active and passive capping technologies can be used both for the site of removal and the site of disposal. Active capping technologies can also be used in landfill liner systems to similar effect: treating as well as containing contaminants. If we momentarily blur the sharp distinctions drawn in the text between dredging, capping, and disposal technologies, we can consider hybrid strategies. Hydraulic dredgers can pipe sediment to nearby locations for containment. Active and passive capping technologies can be used both for the site of removal and the site of disposal. I propose exploring the territory between in situ and ex situ disposal. One possible metric to us in gaging the capacity for remedial strategies to impact the environment: the greater the distance that PCB sediment travels, the greater the ecological disruption. At the heart of my proposal lies the belief that Berkshire County is equipped to manage its own PCB waste disposal. The region's emphasis on local economies and ecological stewardship offer infrastructure upon which PCB management could be extended. Berkshire County is poised to become a prototype for local hazardous waste management, taking a stand against current trends of off-shore outsourcing of toxic waste.

Sustainable disposal strategies demand adjusting a "not-in-my-backyard" attitude to hazardous waste. Carbon footprint and environmental justice issues make out-of-state disposal options unideal, and Berkshire County has the resources-and perhaps the inclination—to locally manage the remediation of the Houstonic River over the longterm. The management of this remediation project is discussed in the final chapter, but here it is critical to note that the decision to dispose of PCBs locally demands a commitment to management that will extend onto future generations. General Electric re-approriating funds away from sediment transport and toward broader projects of river stewardship, including programs of habitat restoration, human recreation, and improving aquatic ecosystem function. If the residents of Berkshire County feel capable of such a project, the value of the Housatonic River can improve far beyond the immediate return from dig and dump operations.

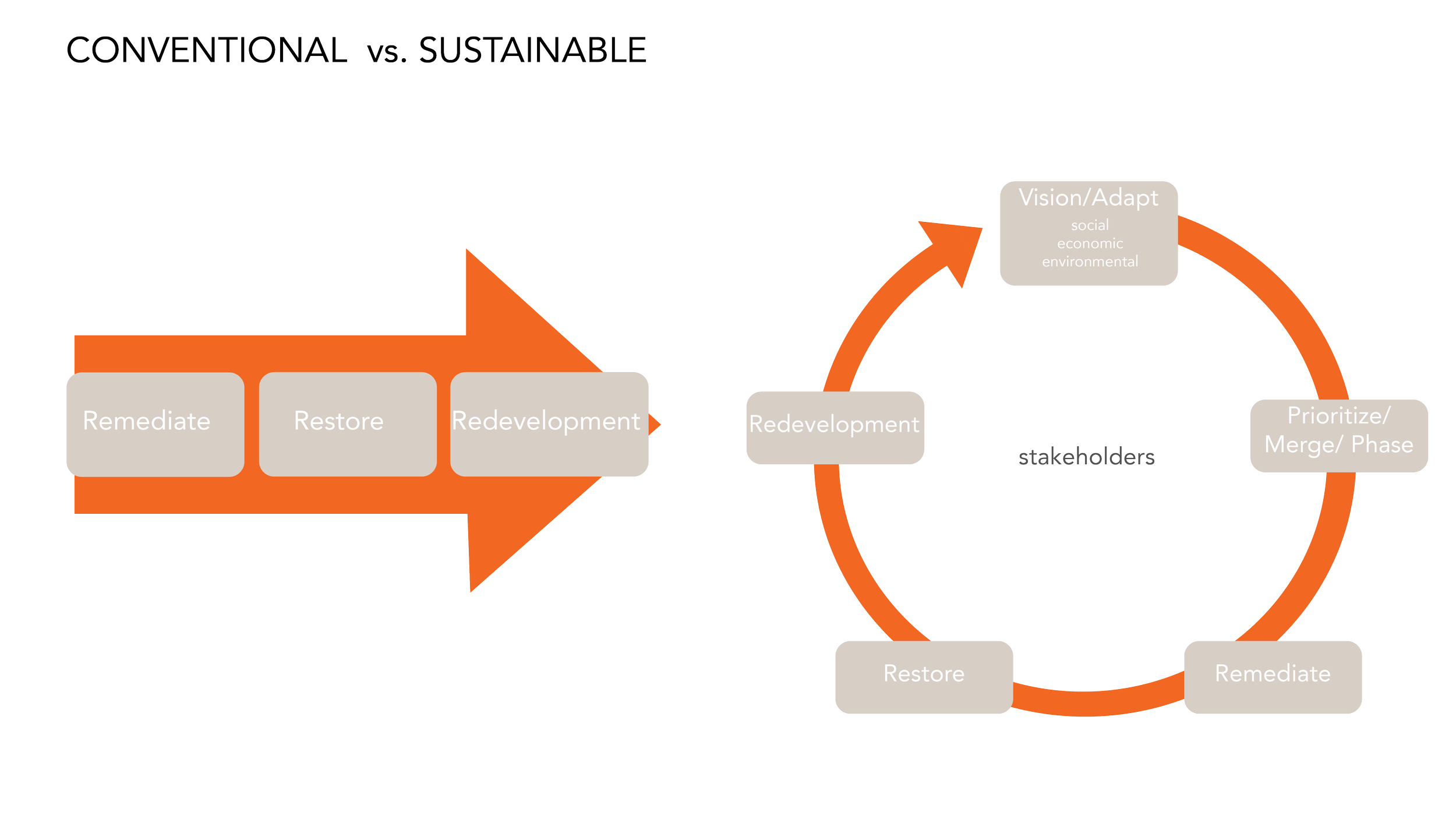

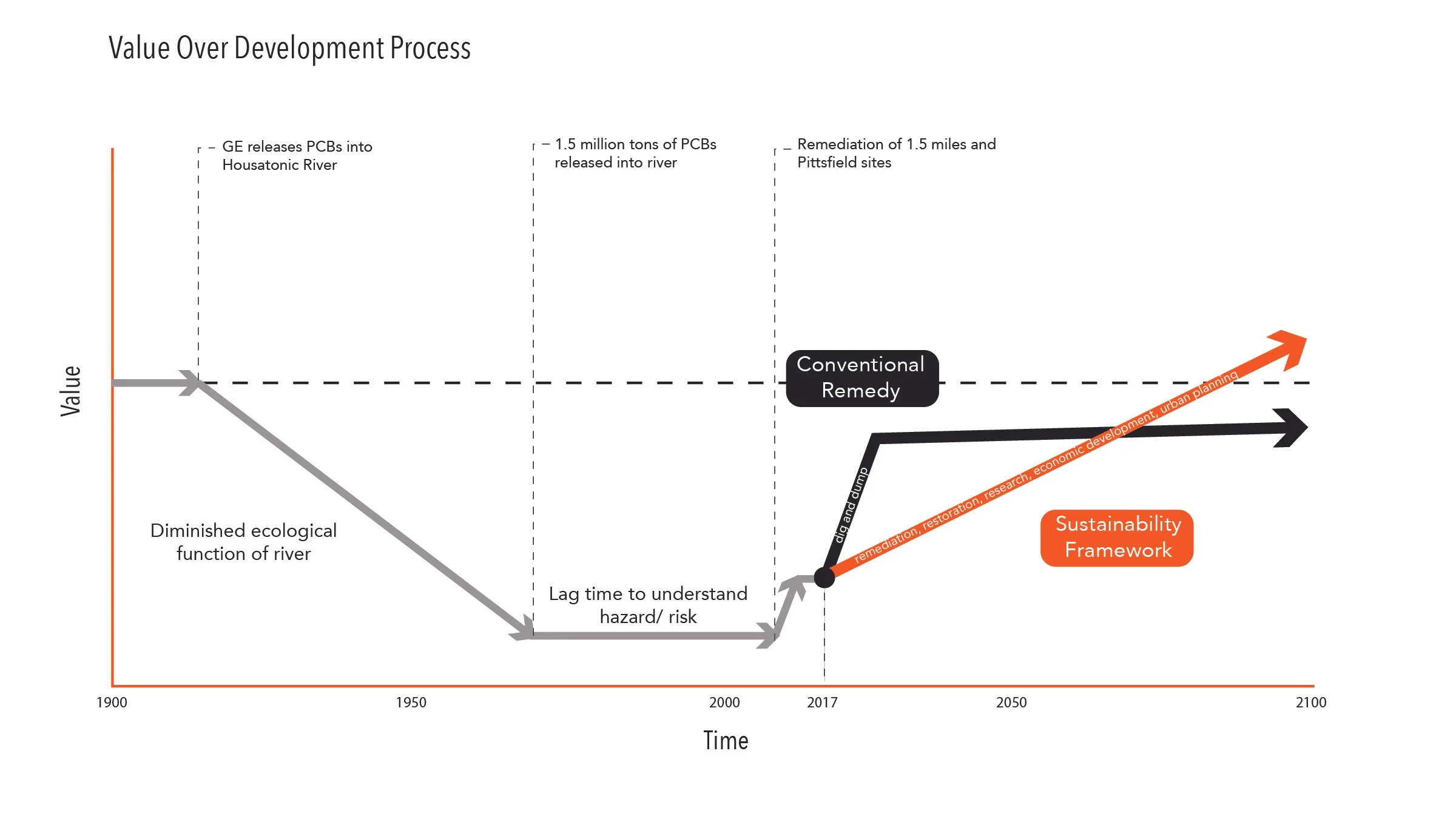

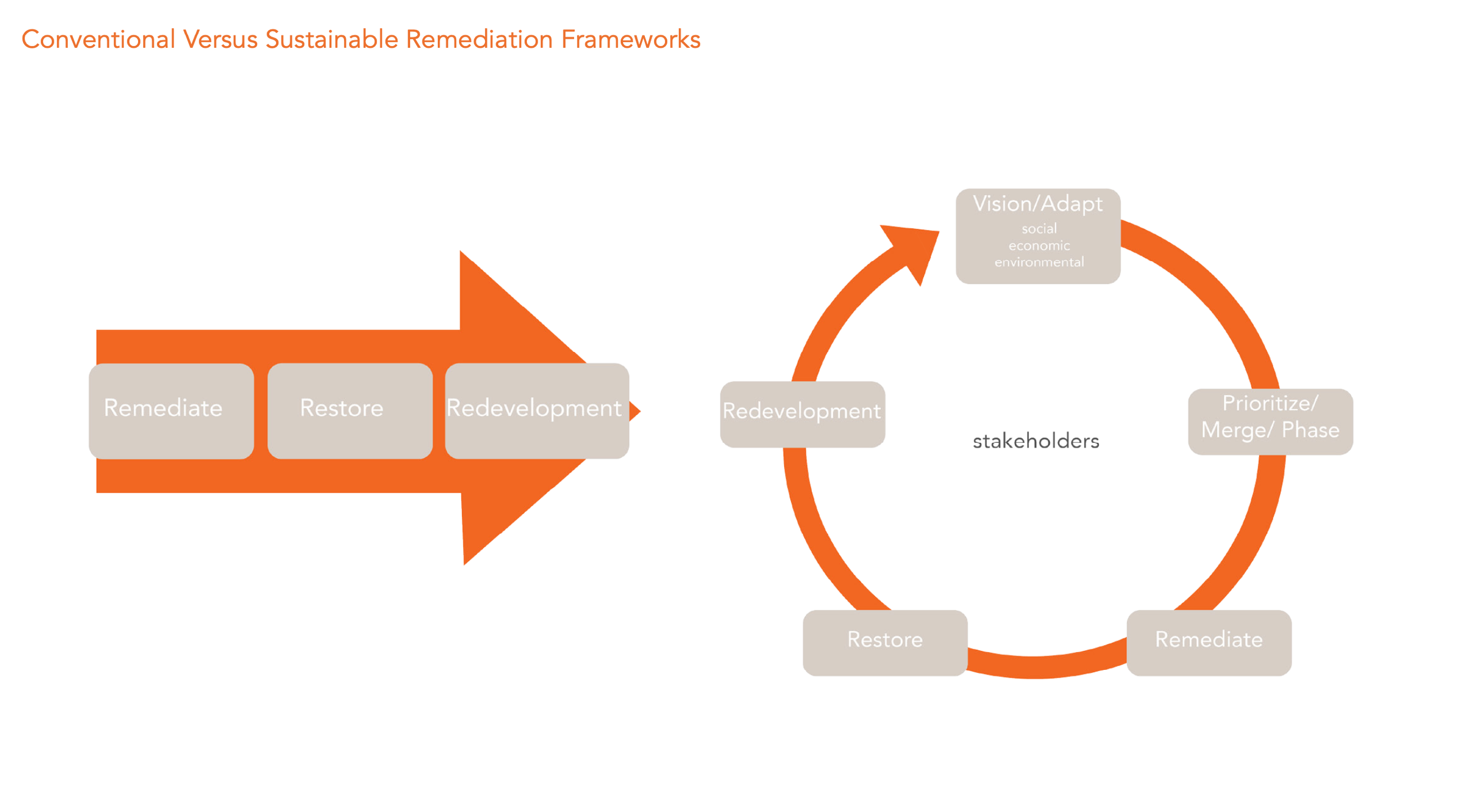

The "Conventional Versus Sustainable Remediation" diagram proposes shifting from a linear workflow to a circular one; we don't need a blueprint, we need a management framework. The "Value Over Development" diagram shows that a sustainable approach will increase the value of the Houstonic River more gradually, but that over time the values of the river will surpass that of dig-and-dump operations. A longer term approach allows remediation strategy to adapt over time, possibly even incorporating promising bioremediation technologies that would actually work to treat PCB contaminants instead of simply storing them.

Notes:

—49. Gomes, Helena I. et all. "Overview of in situ and ex situ remediation technologies for PCB-contaminated soils and sediments and obstacles for full-scale application." Science of the Total Environment. 445-446 (2013) 237-26

Fig 26.

Conventional river restoration follows a linear model focused on removal and disposal, while cyclical, sustainable restoration emphasizes ongoing ecological processes, material reuse, and adaptive management to support long-term river health and resilience.

Fig 27.

The decline of ecological function follows the release of 1.5 million tons of PCBs into the Housatonic River. A conventional remedy offers immediate ecological rebound, whereas a sustainability framework offers a more gradual rise in ecological performance, surpassing a conventional remedy over time.

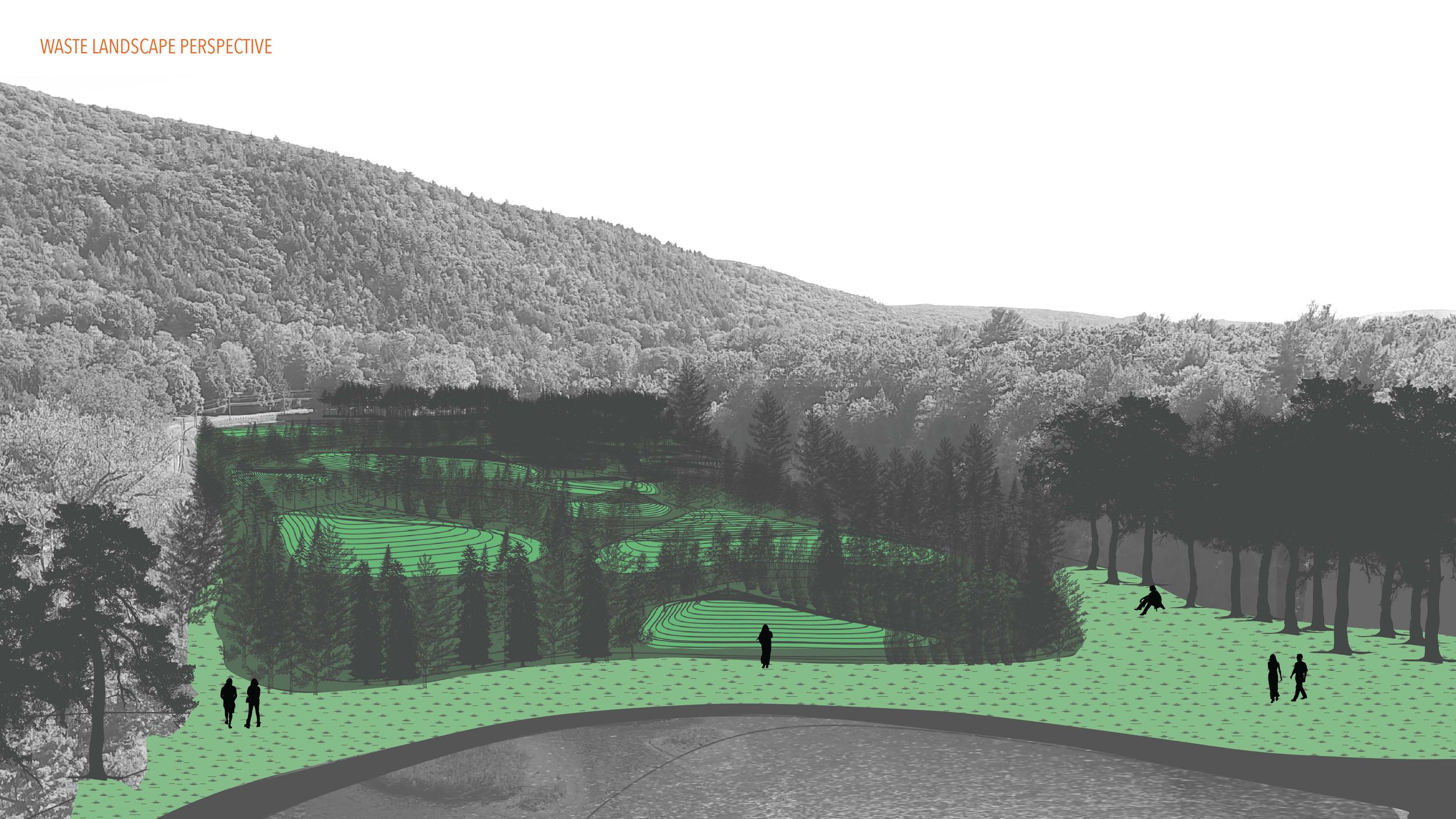

The following images outline specific interventions that follow a sustainable approach to PCB remediation: