APPROACHING DEFORESTATION ECONOMIES IN PARAGUAY:

Research Methods for Mapping Forest-to-Export Supply Chains

by Malcolm Wyer

ABSTRACT

Between 1987 and 2023, Paraguay lost approximately 8.5 million hectares of forest, making it one of the most deforested countries on Earth. This report begins at global scale, tracing the trade dynamics, commodity demand, and regulatory frameworks that shape incentives for forest conversion, then narrows to the Chaco itself, examining the corporate structures, bureaucratic chokepoints, and financial pathways through which timber is extracted, processed, and legalized for export. It profiles three companies—Bricapar, EFISA, and Madexport—whose contrasting strategies illuminate how Paraguay's timber sector operates in legal gray zones: political connection, offshore opacity, and mixed sourcing that defeats traceability. Ultimately this report does not offer strategic recommendations but rather reflections on what investigative work can accomplish when the systems designed to act on it have failed. It argues that the making the record visible remains necessary even when it doesn't produce reform, because the question is not only whether actors change behavior but how far information travels and into which conversations it enters. Deforestation in Paraguay will not stop because of a change in attitudes. It will stop because the forest is gone. When that transition comes, someone will need to have documented how it happened, who profited, and what was lost.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MERCOSUR, the EU, and the Leakage Problem

Paraguay’s Trade Flows to MERCOSUR Shipping Ports

Paraguay’s Timber Industry & More Leakage

Forest Law, INFONA & State Monitoring

Sawmills, Wood Exporters, and Charcoal Exporters

Corporate Structures: Bricapar S.A., EFISA, and Madexport Paraguay S.A.

Conversion Points, Money Laundering & SEPRELAD

Making The Record Legible & A Final Note

References

1. MERCOSUR, the EU, and the Leakage Problem

On 17 January, 2026, the EU and MERCOSUR signed their long-awaited Partnership Agreement in Asunción, creating what proponents hailed as the world's largest free trade zone—700 million consumers, 30% of global GDP, and the elimination of over 90% of bilateral tariffs.

Yet the agreement's sustainability chapter reveals the tension at the heart of European trade policy: environmental provisions cannot trigger sanctions or trade suspension, and the deal explicitly commits the EU to give MERCOSUR countries favorable consideration in risk classifications under its own deforestation regulations. The ink had barely dried before the European Parliament voted 334-324 to refer the agreement to the European Court of Justice, a move that could delay implementation by two years.

At the heart of the delay lies objections from broad sectors of European agriculture, which point to the leakage problem. In environmental economics, "leakage" refers to the displacement of harmful activities from regulated areas to unregulated ones. EU farmers fear that MERCOSUR agricultural producers, operating without safeguards on labour standards, deforestation, pesticide use, and carbon emissions, will undercut them on price and threaten their livelihoods. Economist Maximiliano Ramírez said. "They do not see it as free trade, but as a transfer of market share toward producers operating under looser rules, which threatens the profitability of mid-sized farmers in countries like France or Ireland."

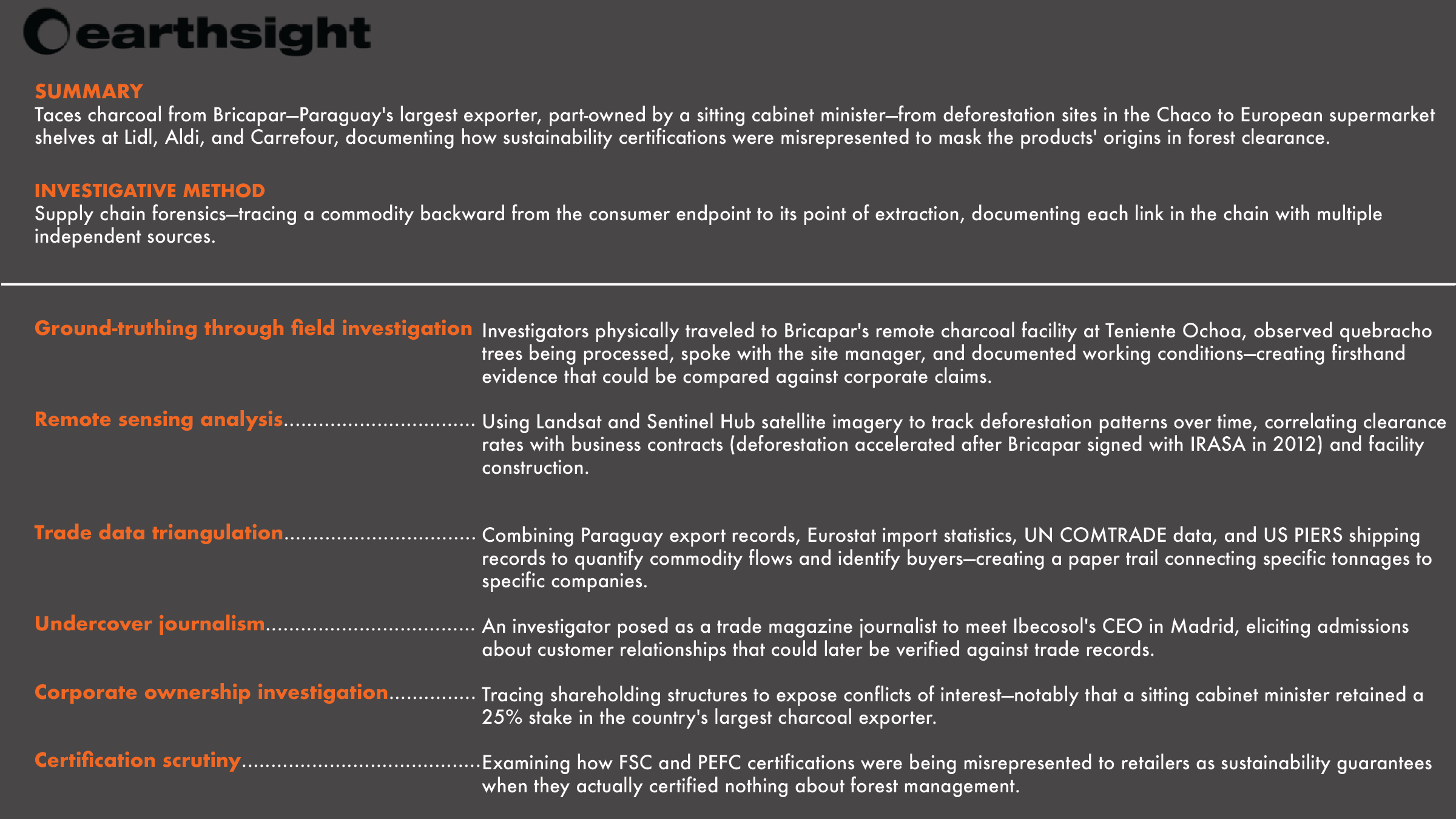

Whether or not the EU-MERCUSOR environmental standards are stringent or diluted, the leakage problem doesn’t end there. As China has grown from 1% of MERCOSUR's export destinations in 1990 to 26% in 2023 (Felter and Renwick, "Mercosur: South America's Fractious Trade Bloc"), it has emerged as the primary alternative market for commodities squeezed out of European supply chains. Any increased regulation around product traceability in the European market means that illegal and unsustainable products will simply flow to markets without equivalent requirements, like China.

MERCOSUR Trading BLOC

Figure 1. MERCOSUR member states—Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia—collectively function as a global agricultural powerhouse, exporting soybeans, beef, corn, leather, iron ore, and timber primarily to China (26% of exports), the European Union (13%), and the United States (10%).

Figure 2. MERCOSUR has been negotiating a trade agreement with the European Union for over two decades. The deal has faced opposition from European farmers and environmental groups concerned about deforestation-linked commodities—beef, soy, leather—entering EU markets. The EUDR and the MERCOSUR-EU agreement exist in tension: one seeks to restrict deforestation-linked imports, while the other would ease market access for precisely those commodities.

Figure 3. This graph from the Council on Foreign Relations shows that "China currently ranks as South America's top trading partner...and some economists predict that [China-Latin America trade] could exceed $700 billion by 2035." (Diana Roym, "China's Growing Influence in Latin America.")

Process Note

Before zooming into national or regional dynamics, I started by mapping trading pressures at a global scale. Reading about international forestry regulation efforts introduced me to the concept of leakage as an organizing framework for understanding how environmental policy in one jurisdiction reshapes commodity flows elsewhere. Ultimately, my biggest takeaway from this brief analysis of Mercosur's relationship to global trade is that focusing on the US and the EU (the traditional targets of supply chain advocacy) is important but incomplete. The rapid growth of China as Mercosur's primary export destination represents the most urgent tension for further inquiry.

2. Paraguay’s Trade Flows to MERCOSUR Shipping Ports

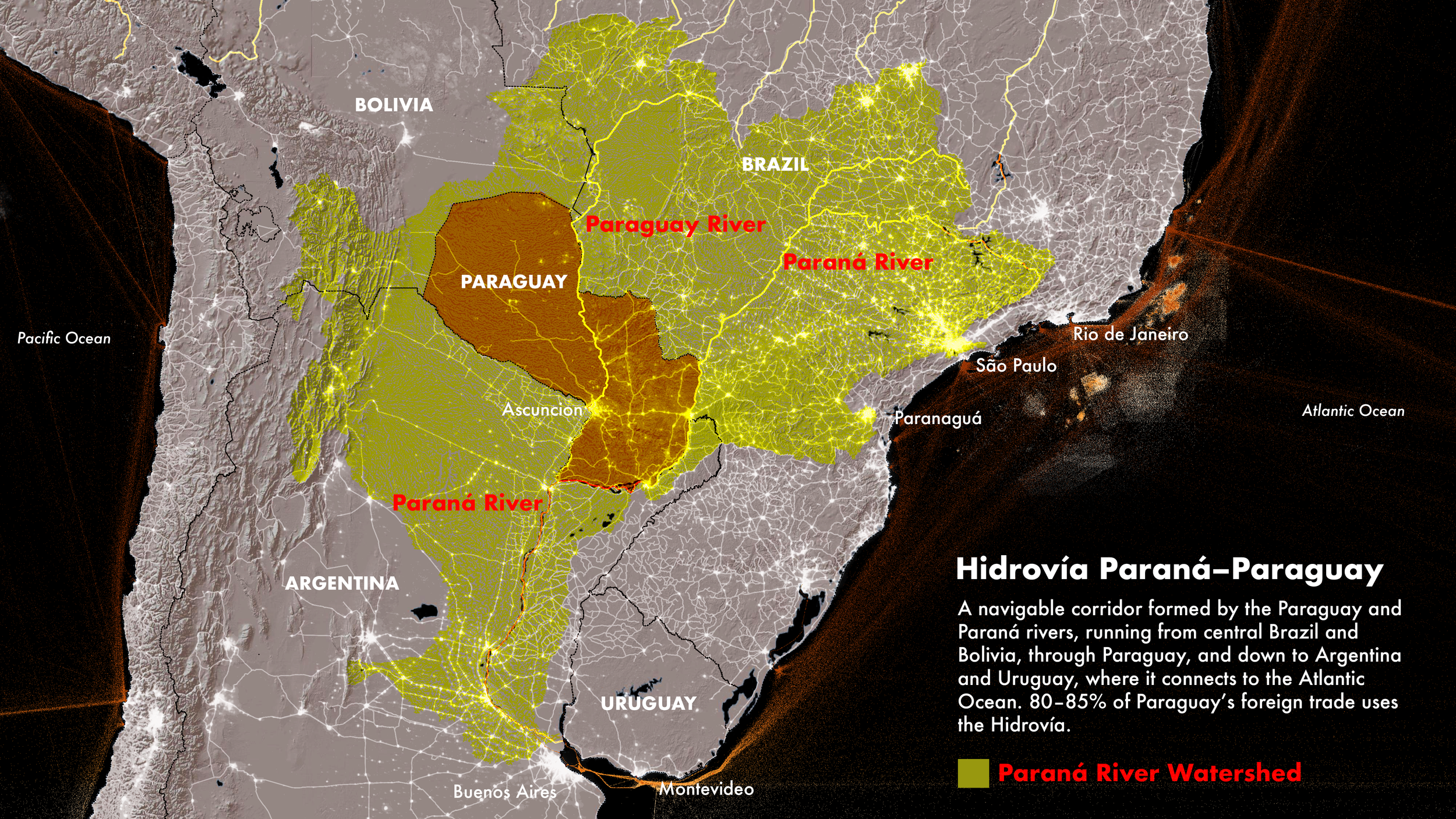

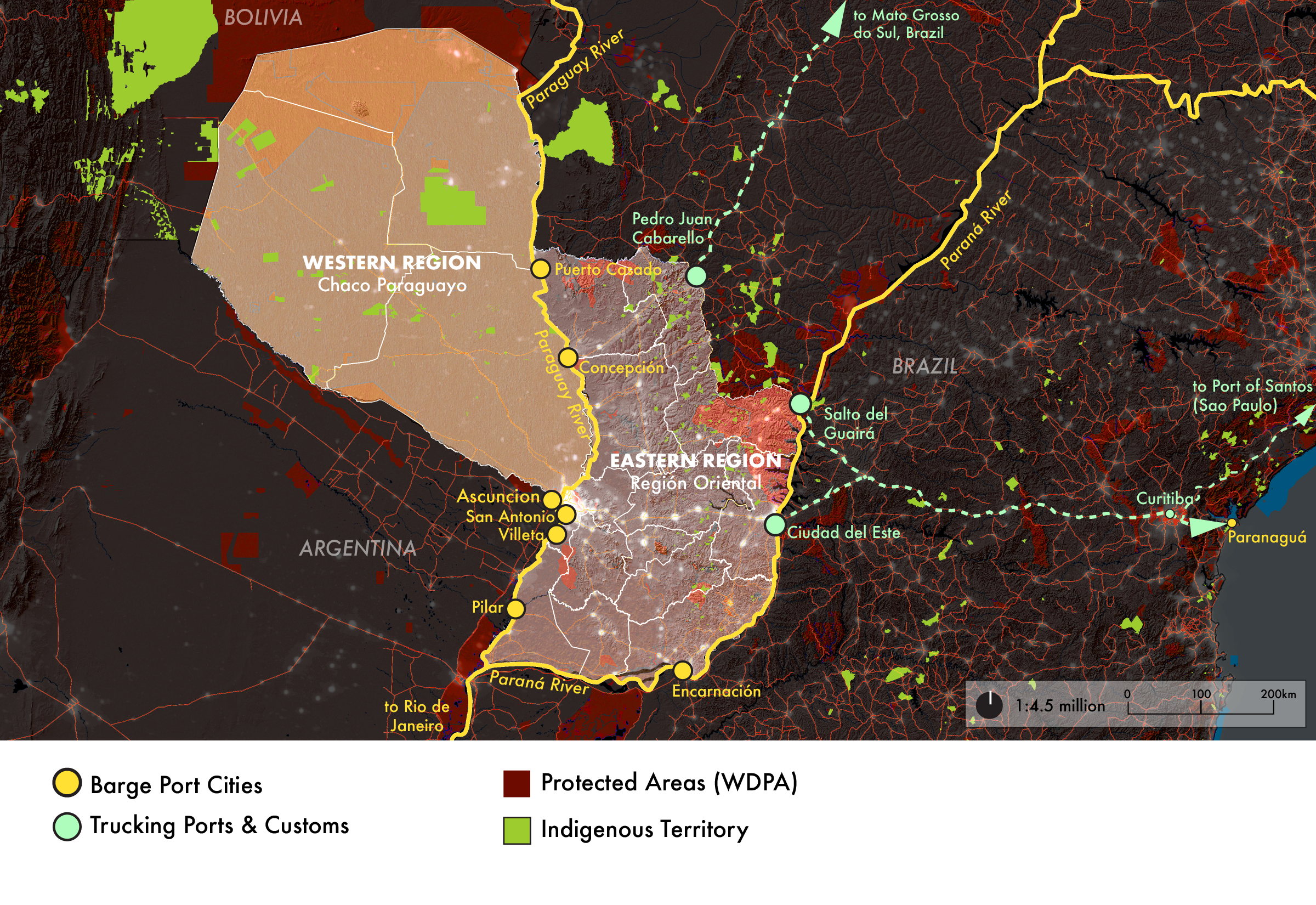

Paraguay occupies a strategic position within the Paraná River basin, connected via the Hidrovía Paraná-Paraguay to major MERCOSUR ports including Rosario and Buenos Aires in Argentina, Montevideo in Uruguay, and Santos and Paranaguá in Brazil. While trucking routes to Brazilian Atlantic ports dominated export logistics from the 1970s through the early 2000s, dramatically lower fuel costs per ton-kilometer have shifted the balance decisively toward barge shipping, with approximately 80 percent of the region's grain exports now moving by water (Durand-Morat, “Agricultural Production Potential in Southern Cone”).

The 3,400-kilometer waterway system transforms Paraguay from a geographical disadvantage into a logistical linchpin: Asunción, Villeta, and other Paraguayan river ports serve as collection points where soybeans, beef, and timber products are loaded onto barge convoys that float downstream to deep-water ports for transshipment to global markets. This infrastructure makes Paraguay a shipping powerhouse despite its landlocked status. The country's flag fleet ranks among the largest in South America, and the volume of cargo transiting its waters rivals that of its coastal neighbors.

Hidrovía Paraná-Paraguay

Figure 4. The Hidrovía Paraná-Paraguay is South America's most commercially important river route—stretching over 2,000 miles and connecting more than 100 inland ports, moving more than 100 million tons annually. The Board of Trade of Rosario (BCR) forecasts that by 2030, countries in the Paraguay-Paraná river basin will supply 40% of the world's grain. (Gregory Ross, "U.S. and China Spar for Influence on the Paraguay-Paraná River System”)

“ Paraguay has developed a modern fluvial logistics sector that moves most of the domestic production via barges through the Paraná and Paraguay rivers. Around 80% of Paraguay’s exports are via barges down the Paraguay–Paraná waterway, which are then consolidated into ocean freights at ports downriver, primarily in Rosario, Argentina, and Palmira, Uruguay. The port export capacity increased 10 times since the mid-2000s with the construction of 22 new ports to attend the growing agricultural exports”

Figure 5. Transport barges navigate the Paraná River in Argentina's Santa Fe province. Photo: Fundación Humedales.

Shipping Ports in Paraguay

Figure 6. Road transport to Brazilian Atlantic ports like Santos and Paranaguá dominated Paraguay's export logistics for decades, but rising fuel costs shifted the calculus. Since the early 2000s, barge traffic on the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway has surged, particularly for high-volume, low-margin commodities like soybeans and lumber where transport costs directly impact profitability. The tradeoff is straightforward: barges move bulk cargo cheaply but slowly, and seasonal fluctuations in river depth can disrupt schedules. Trucking remains essential for exports destined for neighboring Brazil and for goods that can't wait for the river. (Reuters, "Analysis: Paraguay on Track for Record Soy Crop, but Low River Levels Slow Exports”).

Process Note

I do not make maps as illustrations of finished research, but instead, mapmaking is central to my analysis process. It is often my very first step. The Paraguay River performs ecologically, logistically, bureaucratically, and symbolically, and here shipping ports function as consolidation nodes. The origin of products before these points are often obscured. Mapping ecological systems together with economic and cultural data allows me to perceive landscapes as social-ecological systems. These maps argue for why MERCOSUR is critical for Paraguay’s export economy. For a landlocked country like Paraguay, MERCOSUR guarantees access to Argentine and Brazilian ports, facilitates the barge traffic that carries exports down the Paraguay-Paraná Waterway, and provides the legal framework for cross-border trucking to Atlantic ports like Santos and Paranaguá. The legality of exported goods, however, is likely manufactured upstream, long before the cargo is loaded onto barges.

3. Paraguay’s Timber Industry & More Leakage

The Paraguayan Chaco is disappearing. Between 2012 and 2017, the Paraguayan Chaco lost native vegetation at an average rate of more than 540 hectares per day (IUCN NL, "Tackling Uncontrolled Deforestation in Paraguay by Improving Landscape Planning). Earthsight concludes in Grand Theft Chaco that "no commodity in the world is responsible for more deforestation than Paraguayan beef and leather." What makes this devastation particularly striking is its legality: Paraguay's Forest Authority estimates that 76 percent of recent forest conversion was authorized under current law. The Chaco is not being destroyed despite Paraguay's regulatory framework; it is being destroyed through it.

Here the leakage problem rears its ugly face again, first at the regional scale with relation to Brazilian regulations and then within Paraguay’s own borders. Brazil's significant legislative interventions, including the 2012 Forest Code and intensified Amazon enforcement that reduced Brazilian deforestation by 76% between 2005 and 2012, did not eliminate the underlying economic pressures driving forest clearance. Instead, those pressures migrated. As Paraguay's former Environment Minister and current Environmental Prosecutor Luis Casaccia told British MPs, "Ranchers have turned their attention to the Chaco, as authorities in Brazil have clamped down on deforestation" (Vidal, "Clamping Down on Logging in Brazil Moves It to Paraguay").

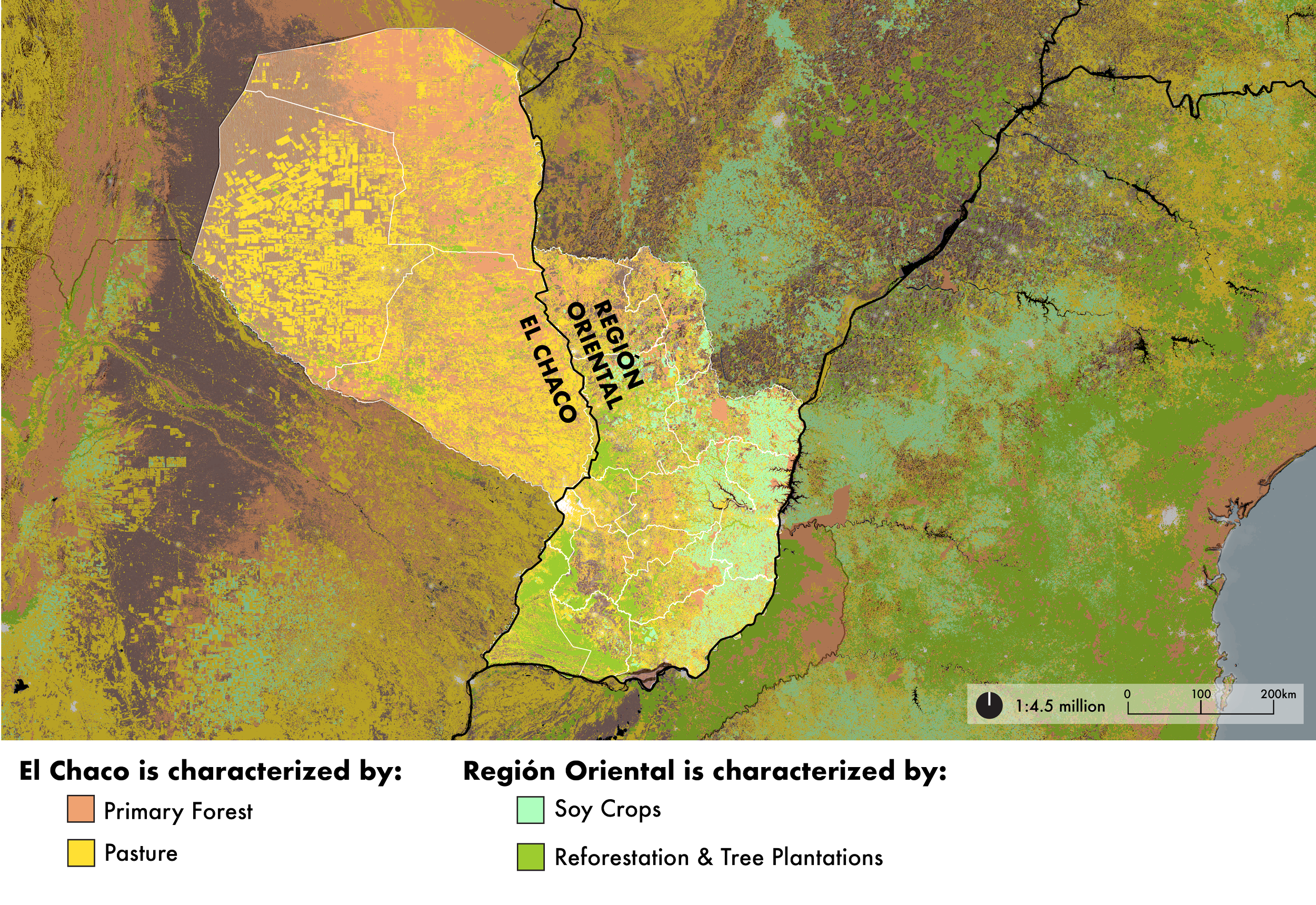

In 2004, Paraguay enacted the Zero Deforestation Law (Law 2524/04), which prohibited the transformation and conversion of forested areas but only in the Eastern Region, home to the remnants of the Atlantic Forest. The law was remarkably effective where it applied: WWF verified that deforestation in the Upper Paraná Atlantic Forest dropped from 88,000–170,000 hectares annually to approximately 16,700 hectares, a reduction of more than 85 percent. Yet the Chaco, comprising 60 percent of Paraguay's national territory and the majority of its remaining forest, was explicitly excluded from the law's protections. The result was predictable: agricultural pressure that could no longer legally clear land in the east simply moved west. Between 2000 and 2015, deforestation in the Eastern Region averaged 63,383 hectares per year, while the Western Region (Chaco) lost 302,797 hectares annually, nearly five times the rate (le Polain de Waroux, "Land-Use Policies and Corporate Investments in Agriculture in the Gran Chaco and Chiquitano). A 2009 proposal to extend the Zero Deforestation Law to the Chaco was vehemently opposed by the agricultural sector and rejected by Paraguay's chamber of deputies, ensuring that the Chaco would remain the nation's deforestation sacrifice zone.

Land Use in Paraguay

Figure 7. Paraguay’s Region Oriental, with higher rainfall, is dominated by soy cultivation and commercial tree plantations. “The production of soybeans, the main agricultural sector in Paraguay, almost doubled in the last decade thanks to a 48% increase in yields and 33% increase in area.” (Durand-Morat, Agricultural Production Potential in Southern Cone.) In contrast, the drier western region, El Chaco, features a mosaic of remaining primary forest and extensive cattle pasture. In the Chaco timber typically enters the supply chain as a side effect of deforestation, not as a classic logging operation.

“The rise in the price of soy in relation to beef created incentives to convert traditional pastures into land for soybean cultivation, driving out and displacing Beef-cattle ranching into cheaper, forested areas. The restrictions on deforestation legislation in neighboring countries, and the approval in 2004 of the zero-deforestation law which affected the eastern region of Paraguay, prompted a significant number of agricultural producers and investors from Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, and eastern Paraguay to purchase large areas of land in the Paraguayan Chaco.”

“Countries experiencing a transition from net deforestation to net reforestation (i.e. a forest transition) due to strict land-use policies could do so in part because they increased their imports of wood products from laxer neighbors… The pollution haven hypothesis (PHH) states that as barriers to trade and foreign investments are removed, companies will relocate polluting activities with weaker environmental regulations.”

“In the Paraguayan Chaco, an annual rate of deforestation of 1.0 percent was reported between 1987 and 2012, with a total loss of 44,000 km2 of forest. Silinas et al. report a deforestatiion rate of 32.3 percent between 1999 and 2021. Fundamentally, land use is changed from forest to grassland for animal feeding. The rate of deforestation more than doubled between 2001 and 2012, being at present one of the most active deforestation frontiers in the world.”

Figure 8. In the Paraguayan Chaco—seen here along the northern Bolivian border—livestock expansion is taking place through very large, highly specialized in Beef-cattle and export-oriented ranches. The Paraguayan Chaco has registered an increase in the number of cattle heads of 60% in the last decade (Milan and Gonzalez). Much of the correlated deforestation (perhaps four-fifths) is completely legal. However, the Paraguayan timber economy depends on INFONA permits that are not easily auditable.

Process Note

Sometimes mapmaking involves exaggerating visual details like contrast or brightness in order to make a subtle landscape change legible to the viewer. Not here. For Figure 8 (Forest Loss GIF) I employed the incredibly high-resolution Hansen rasters of “21st-Century Forest Change,” which contains values for forest loss per year between 2000-2024. The data show an absolute annihilation of primary forest in the Paraguayan Chaco. A deforestation emergency this dire—while 76% legal—conjures in me a cynical dread: the deforestation rate will likely only decelerate because primary forest has already been eradicated. What disappears in these frames is irreversible during any human time scale, and what replaces it may not remain viable for long. Without contiguous forest cover, the Chaco loses its capacity to buffer droughts, regulate flooding, and sequester carbon, and the intensive Beef-cattle export industry replacing it accelerate this degradation through soil compaction, erosion, and salinization. The Paraguayan Chaco is crossing into afterforest.

4. Forest Law, INFONA & Monitoring

The scale of legal deforestation in Paraguay becomes legible through the Paraguay's foundational 1973 Forestry Law (Law 422/73). It establishes that private landowners in the Chaco who wish to clear forest must obtain authorization from both the Ministry of Environment (MADES) and the National Forestry Institute (INFONA), and must maintain 25 percent of their property's native vegetation as a "forest reserve," with an additional 15 percent retained as protective strips between 100-hectare bands of cleared land. What this framework permits, however, is the legal conversion of up to 60 percent of any given property, and when applied across millions of hectares of privately-held Chaco land, the cumulative authorization is staggering.

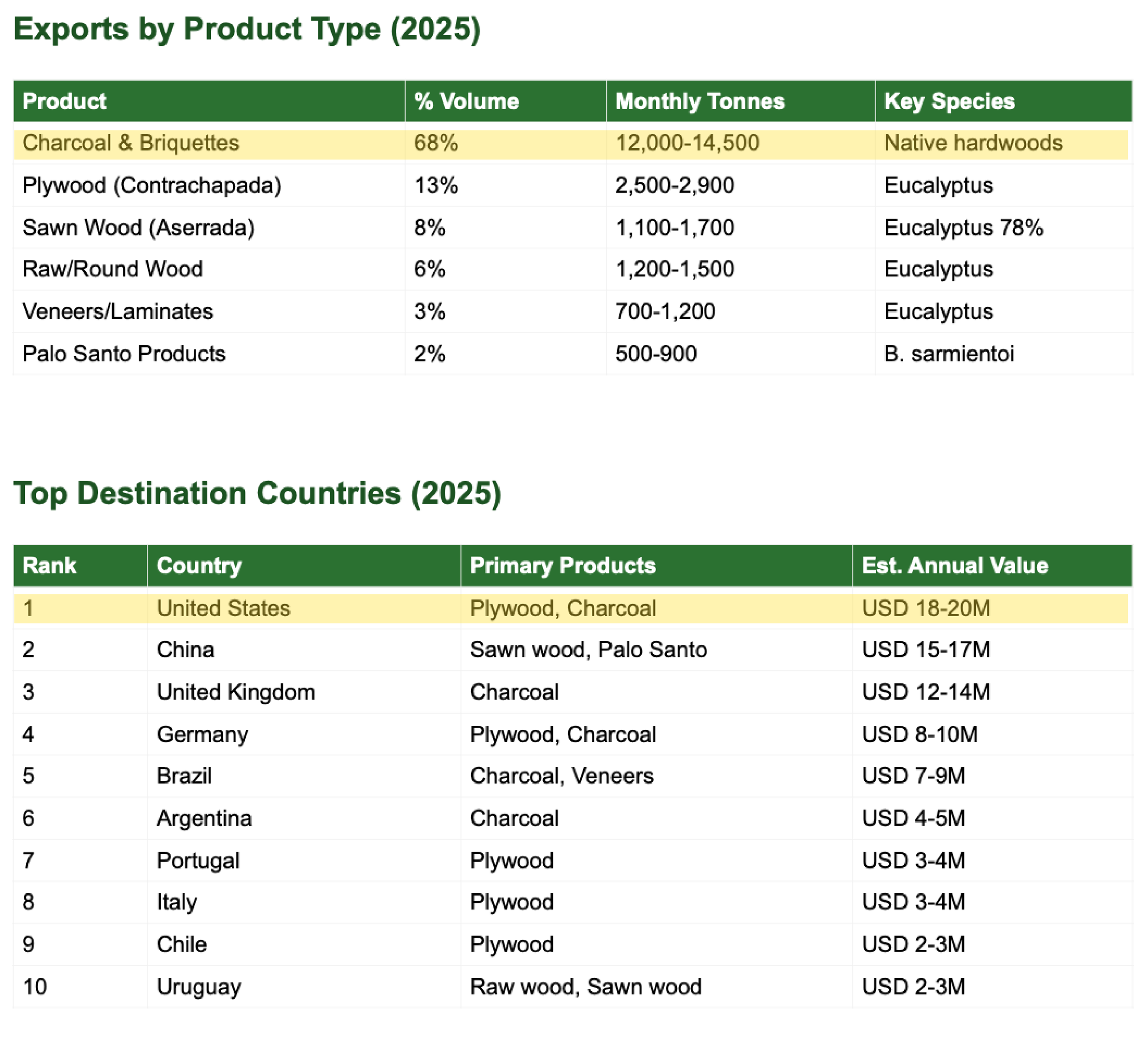

What drives this legal clearing is not timber extraction but pasture expansion for cattle ranching; cropland conversion plays only a minor role. This distinction is critical for understanding Paraguay's timber export profile. According to INFONA data, charcoal and briquettes account for 68 percent of Paraguay's timber export volume and are produced almost entirely from native hardwoods. By contrast, plywood (13 percent), sawn wood (8 percent), raw wood (6 percent), and veneers (3 percent) rely predominantly on Eucalyptus from the country's expanding plantation sector. The charcoal industry, in other words, is not harvesting timber from standing forests; it is processing the byproduct of forest clearance for ranching. The economic logic is not forestry but land conversion, with charcoal production serving as a revenue stream that partially offsets clearing costs while feeding export markets.

INFONA's monitoring capacity is structurally inadequate to the scale of the problem. The agency's own analyses suggest a minimum of 20 percent of Chaco deforestation is illegal, yet as one Paraguayan environmental prosecutor observed, "there's not a single person in prison for this." (Earthsight, Grand Theft Chaco). Satellite imagery has made it impossible for illegal deforesters to hide their activities, but detection has not translated into enforcement. INFONA has approximately 554 registered forest industries under its purview, including 388 sawmills, 83 laminators, and 55 charcoal producers, with direct employment of fewer than 6,000 workers. The agency operates across a vast territory dispersed with remote ranches accessible only by unpaved roads. Even when illegalities are documented, as in Earthsight's investigations of deforestation within indigenous protected areas, INFONA's responses have been described as "subdued or downright reckless." (Earthsight. "Paraguayan Authorities Complicit in Illegal Razing of Country's Forests by EU-Linked Agribusiness”.)

The structure of land ownership compounds these governance failures. Paraguay has the most unequal land distribution of any country in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.93 (World Bank, A Forest’s Worth: Policy options for a sustainable and inclusive forest economy in Paraguay.) Ninety percent of Paraguayan land is controlled by approximately 12,000 large property owners, and more than 70 percent of productive land is occupied by just 1 percent of farms (Earthsight, Grand Theft Chaco)—holdings that resemble the latifundia system that has characterized South American agriculture since the colonial period. This concentration has two effects. First, it means that decisions about forest conversion are made by a small elite whose interests align with export-oriented agribusiness rather than sustainability. Second, it creates what Earthsight describes as an "intimacy between political power and land ownership" that undermines regulatory independence. When the people who write the laws and the people who own the land are the same, enforcement becomes self-regulation.

Figure 9. Data for 1973–1989 (~175,000 ha/year) represents a period average from Huang et al. Landsat analysis of the Eastern Region, where deforestation was concentrated almost entirely in the Atlantic Forest, driven by soy expansion and colonization following the Itaipú construction boom. The 1990–2000 figures (~179,000 ha/year) derive from FAO Forest Resources Assessment period averages, combining declining Eastern Region losses with gradually rising Chaco losses during a decade in which Paraguay lost approximately 13% of its total national forest cover. Annual data from 2001–2023 comes from Global Forest Watch / University of Maryland GLAD, though methodological differences mean figures are not directly comparable across eras.

INFONA Resources:

2025 Commerce Summary: Paraguay_Timber_Commerce_Overview_2025.pdf

Data Sources: INFONA_Data_Sources.pdf

New Forest Policy 2025: INFONA_Politica_Forestal_Nacional_2025.pdf

Information Request: Under Ley 5282/2014 (Paraguay's Freedom of Information law), you can submit a formal request to INFONA for permit data via: registropublicoforestal@infona.gov.py or secretaria.general@infona.gov.py

Contact INFONA directly: Their main office is at Ruta PY02 - Mariscal Estigarribia, San Lorenzo. Phone: 021 729 3500

“The National Forestry Institute (INFONA) is tasked with the administration, promotion, and development of forest resources and value chains, to maximize the sector’s economic potential. INFONA has 185 employees in their Asunción headquarters and another 195 employees in regional offices. Some regional offices are understaffed, such as those in Boquerón and Alto Paraguay, which count only three employees each to oversee an area of 9.17 million ha and 8.23 million ha, respectively.

In contrast, the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MADES) is in charge of environmental policy more broadly (Law 1561/00). Forests fall within the ministry’s scope since it issues and implements environmental regulation, such as the Environmental Services Regime (Law 3001/06).Judicial branch monitoring includes the Public Prosecutor (Minister Publico), and the Supreme Court that protect citizen’s rights to a clean environment and enforces compliance with environmental criminal law (Law 716/96) as well as the Comptroller General (Contraloria).”

Figure 10. According to INFONA data, Paraguay exported approximately 195,816 tonnes of timber products in 2025 (valued at USD 100.6 million, with charcoal and briquettes accounting for 68 percent of volume—produced almost entirely from native hardwoods—while plywood, sawn wood, and veneers rely predominantly on Eucalyptus from the country's expanding plantation sector. The United States, China, and the United Kingdom are the top export destinations, and the industry comprises 554 registered forest enterprises (including 388 sawmills and 55 charcoal producers) employing fewer than 6,000 workers, with 70 percent of activity concentrated in five departments.

“Approximately 95% of the land is privately owned by domestic and foreign individuals, corporations, and cooperatives….The Gini coefficient of land ownership stands at 0.93. More than 70% of productive land is occupied by 1% of farms that resemble latifundia-style holdings, making Paraguay the country with the highest level of land inequality in the world.”

Figure 11. Legal deforestation permits are typically granted for land use change—specifically, converting forest to cattle pasture under approved management plans. When satellite imagery reveals cleared areas that remain bare or revegetating rather than converted to productive pasture, this pattern may signal irregularities: either the clearing exceeded permitted boundaries, no valid permit existed, or the stated justification for the permit was fraudulent. Such areas suggest the primary economic motive may have been extracting timber and charcoal value rather than establishing legitimate ranching operations.

Process Note

The fact that 90 percent of Paraguayan land is controlled by approximately 12,000 large property owners appears to be the underlying driver enabling deforestation at this scale; what happens to the forest is decided by the few who profit from its removal. For Figure 9 (Paraguay Annual Deforestation), I merged a quantitative graph with a qualitative timeline, layering deforestation rates against cultural and regulatory context—though this deserves greater resolution and nuance. I suspect Earthsight may already possess parcel-level ownership data, perhaps even geospatial datasets, which I would very much like to work with. In Figure 11 (Looking for Suspicious Deforestation), I wanted to highlight cleared forest that had not been converted to pasture or agriculture—areas where trees have been removed but no productive land use has followed. A logical next step would be to cross-reference these cleared but unconverted zones against INFONA permit records and the 25 percent forest reserve requirement to identify potential violations. This spatial pattern—deforestation without corresponding development—represents a key red flag for enforcement agencies and researchers, as it may indicate speculative clearing, permit fraud, or deliberate circumvention of reserve obligations.

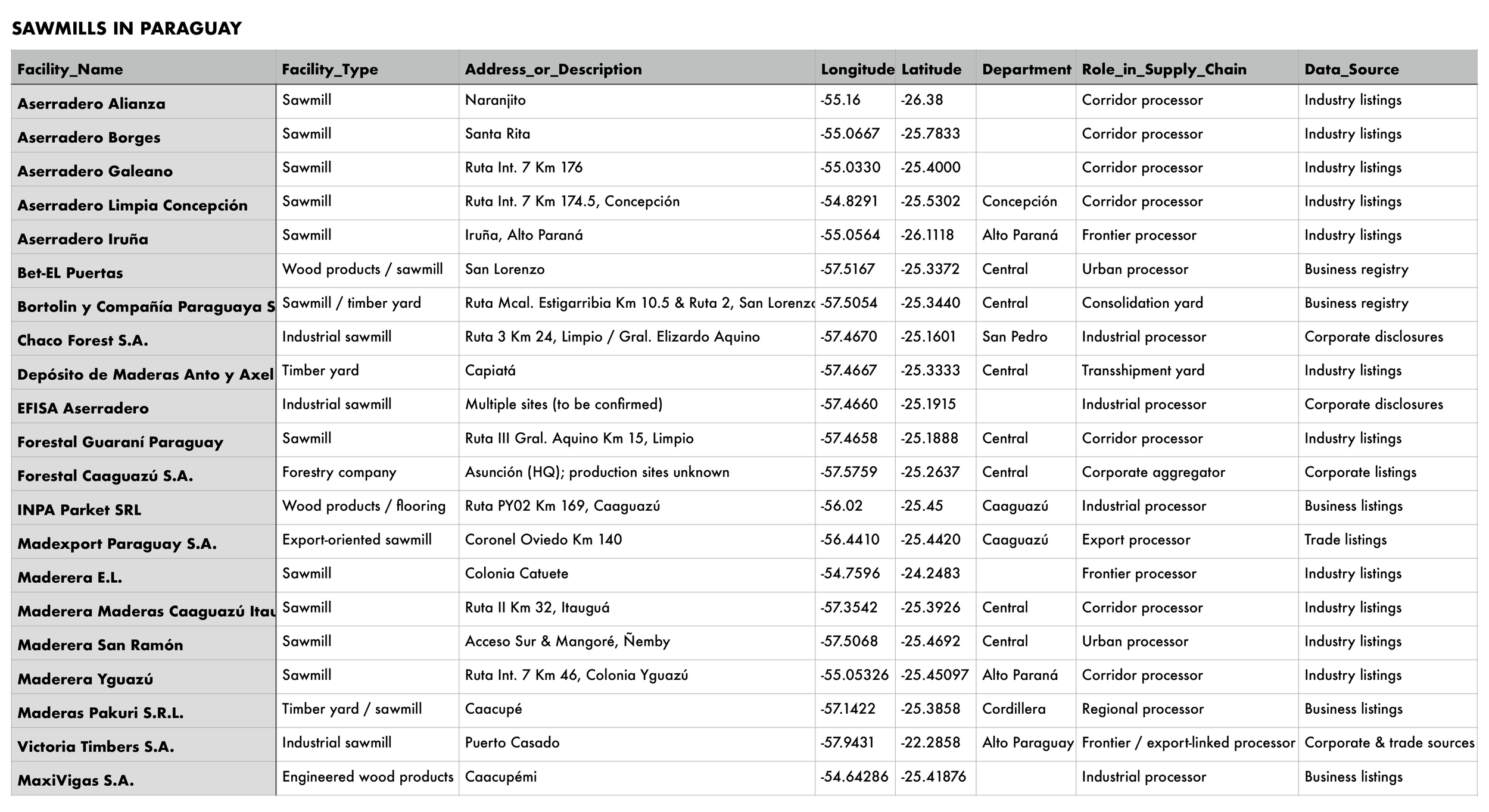

5. Sawmills, Wood Exporters, and Charcoal Exporters

Paraguayan sawmills are distributed along the arterial roads connecting the forested interior to export terminals, with distinct nodes serving different functions. Frontier processors like Victoria Timbers S.A. in Puerto Casado (Alto Paraguay) sit at the edge of the Chaco, positioned to receive timber directly from nearby clearance operations. Corridor processors along Ruta 7 and Ruta 2—such as Madexport Paraguay S.A. in Coronel Oviedo and INPA Parket SRL in Caaguazú—occupy intermediate positions, aggregating material from multiple upstream sources. Consolidation yards clustered in Central Department, near Asunción, function as transshipment points where timber from diverse and often untraceable origins is mixed, reprocessed, and prepared for export. This spatial logic creates chokepoints where traceability dissolves: by the time wood reaches a consolidation yard, its provenance has been laundered through multiple intermediaries, and documentation attesting to legal origin becomes difficult to verify against physical supply.

The charcoal sector operates through a parallel but overlapping infrastructure. Suppliers explicitly state that they use native Chaco hardwoods like Quebracho Blanco, Guayacán, Guamí Piré, and Labón, species prized for their density and high caloric value. Satellite imagery reveals that the Bricapar facility near Teniente Ochoa, which Earthsight investigated in 2015–2017, has since vanished from the landscape, but Figure 15 identifies an active kiln cluster in Alto Paraguay that displays the same spatial signatures: circular clearings with charred centers, arranged in rows along access roads, located within zones of recent forest loss.

What emerges from mapping these networks is a system where illegality occurs precisely where bureaucratic and logistical systems fail to align. A charcoal exporter may present INFONA authorization for "forest management residues," but if satellite imagery shows source coordinates falling within areas cleared without permits—or within the 25 percent forest reserve that landowners are legally required to maintain—the documentation functions not as proof of compliance but as a laundering mechanism.

Figure 12. Once a list of timber businesses was compiled, online research was used to identify publicly available addresses, which were then converted to GIS coordinates for spatial analysis. The resulting maps reveal geographic clusters of timber enterprise, but these visualizations come with significant caveats. Many companies on the list had no publicly accessible address, and those that did frequently listed corporate offices in Asunción or regional capitals, locations spatially divorced from sawmills, kilns, and forest concessions where actual commodity extraction and processing occur. The gap between registered address and operational site represents a persistent obstacle to mapping the true geography of Paraguay's timber economy.

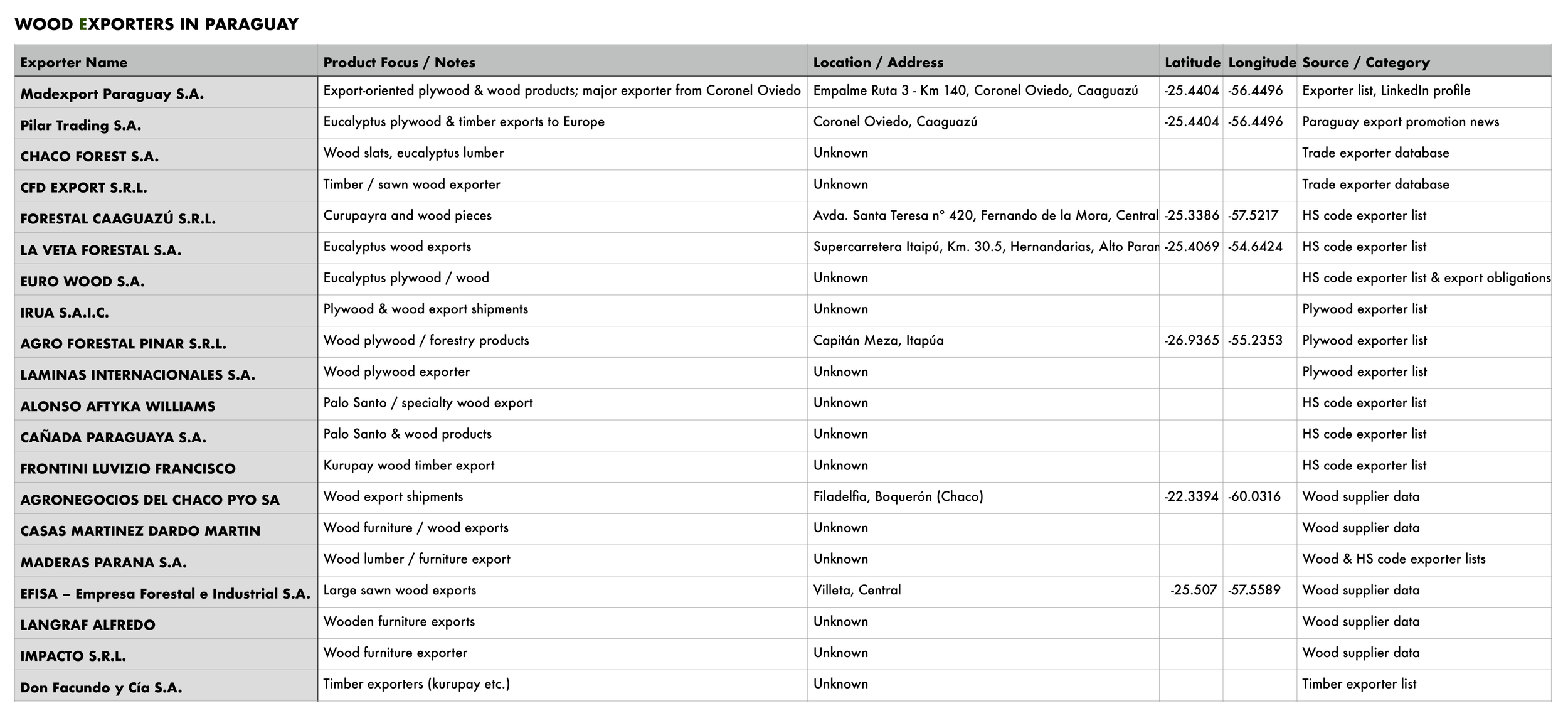

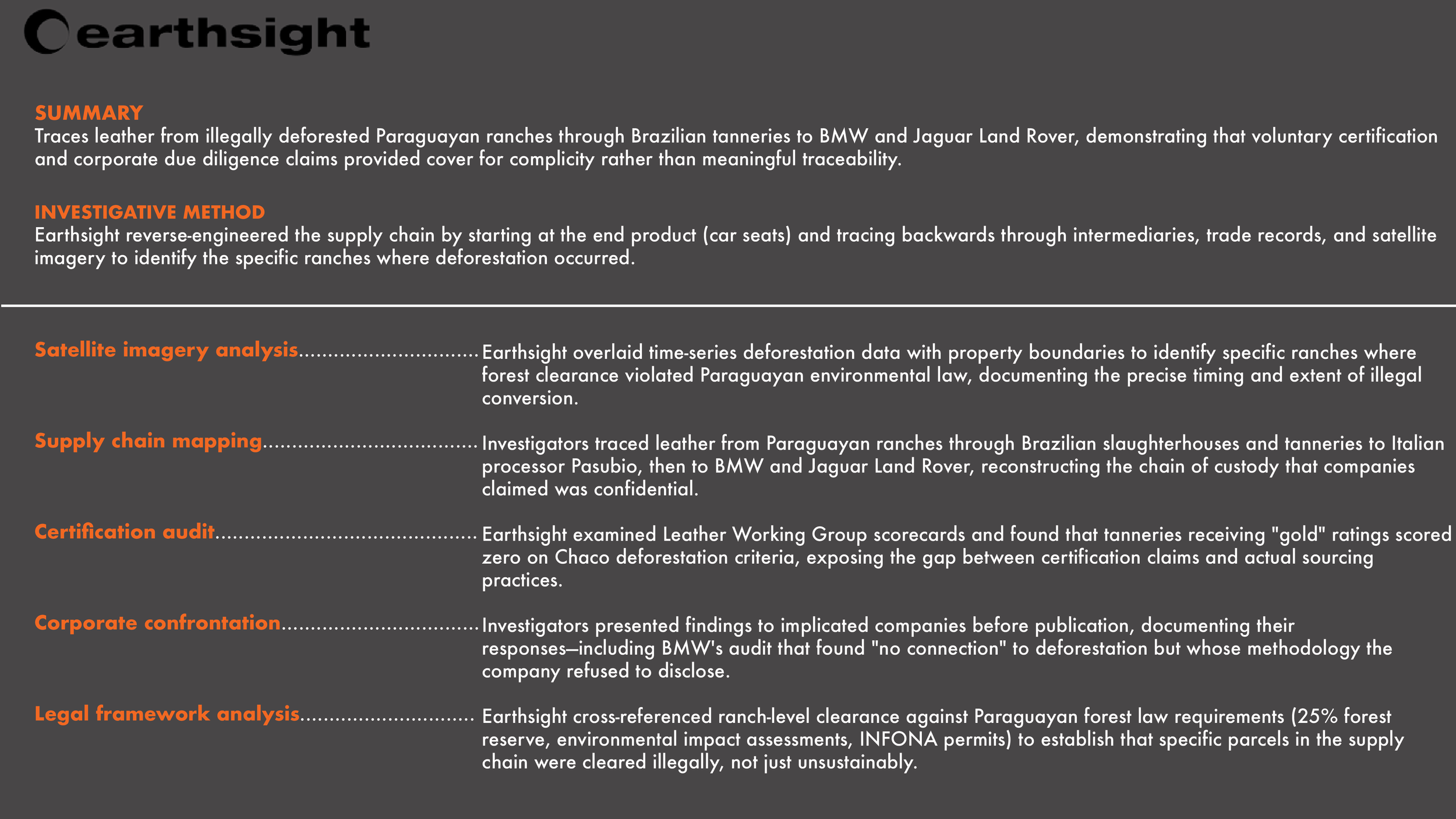

Earthsight Paraguay Investigation

Choice Cuts (July 2017)

Charcoal & Deforestation

Figure 13. Earthsight's 2017 Choice Cuts investigation traced charcoal sold in European supermarkets—including Lidl, Aldi, and Carrefour—to Bricapar, Paraguay's largest charcoal exporter, which was processing native hardwoods cleared from Chaco forests at a rate equivalent to 30 football pitches per day. The investigation revealed that a major shareholder in Bricapar was sitting cabinet minister Ramón Jiménez Gaona, whose ministerial portfolio included infrastructure projects benefiting the company's operations, and that European retailers had accepted FSC and PEFC certifications that misrepresented the sustainability of the products. Following publication, Carrefour suspended sales, PEFC launched an investigation that ultimately stripped Bricapar of its certification, and the Paraguayan congress opened an inquiry into Chaco deforestation.

Figure 14. IRASA is a Paraguayan agricultural company that holds a 20-year lease on approximately 18,000 hectares of land at Teniente Ochoa, land owned by the IPS (Instituto de Previsión Social), Paraguay's state social security fund. BRICAPAR signed a contract with IRASA to produce charcoal on the site. While the permit allowing conversion of natural vegetation to cattle pasture followed standard Paraguayan regulations requiring conservation of 25 percent of total land area plus buffer strips around clearance blocks, satellite images clearly showed that most of the land was being entirely cleared of natural vegetation, activities Earthsight argued constituted deforestation rather than sustainable forestry. By 2023, satellite imagery reveals that the 80-kiln facility has vanished.

How to spot a charcoal kiln from satellite

Figure 15. Charcoal kilns are identifiable in satellite imagery through several distinguishing features: they appear as circular or oval clearings approximately 3–10 meters in diameter, with a dark center (charred earth or ash residue) surrounded by lighter exposed soil. Kilns typically occupy isolated cleared patches within recently deforested areas, connected by small trails or dirt roads used for transporting wood and finished charcoal. They often appear in clusters—arranged in rows or groups—reflecting the industrial scale of production, and may be accompanied by nearby log piles or staging areas where timber is stockpiled before carbonization.

Process Note

My ambition to layer permit boundaries, concession areas, and ownership parcels onto deforestation maps proved impossible with the data currently available. I turned instead to Claude, Anthropic's AI research assistant, to help me trace corporate structures, synthesize scattered secondary sources, and identify patterns across documents that no map could reveal. I began by compiling lists of timber companies in three categories: sawmills, wood exporters, and charcoal exporters. Claude helped me add latitude and longitude coordinates to each entry, transforming my spreadsheet into layers I could load into QGIS, creating the basis for Figure 12. This map is imperfect: many coordinates point to corporate offices in Asunción rather than the actual sites of timber processing. If these points could be refined to reflect physical facilities rather than registered addresses, they would function as consolidation nodes—chokepoints in the supply chain where timber of uncertain origin is aggregated and potential illegality is diluted into undifferentiated bulk. To push further, I turned to Earthsight's publications to learn about supply chain forensics, which led me to satellite imagery analysis. I discovered that the Bricapar charcoal facility near Teniente Ochoa—central to Earthsight's 2017 Choice Cuts investigation—has since vanished from the landscape. But by scanning recent imagery across Alto Paraguay, I was able to identify an active kiln displaying the characteristic signatures: circular clearings, charred centers, arranged along access roads within zones of recent forest loss.

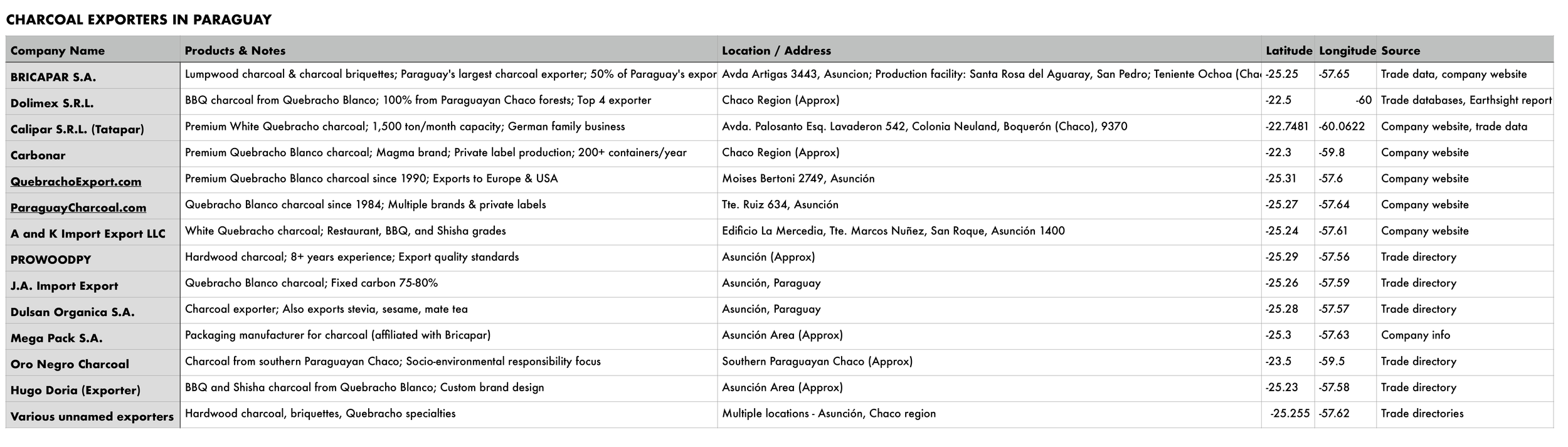

Three Paraguayan timber companies illustrate three strategies for operating in the Chaco's legal gray zone. Bricapar, the country's largest charcoal exporter, is majority-owned by a politically connected family and part-owned by its own European distributor. EFISA, a eucalyptus operation controlled by a German agribusiness family through a British Virgin Islands holding company, markets itself as the sustainable alternative while resisting independent verification. Madexport, a mid-sized sawmill with government contracts, processes both native hardwoods and plantation timber, blurring the line between high-risk and low-risk sourcing.

What connects them is not shared ownership but shared infrastructure: the same regulatory environment, the same certification systems, the same trade association. The Federación Paraguaya de Madereros (FEPAMA) represents over eighty companies accounting for the majority of Paraguay's timber exports. Its president, Manuel Jiménez Gaona, is also president of Bricapar and a director of Ibecosol, the Spanish company that distributes Bricapar's charcoal to Lidl, Aldi, and Carrefour. He simultaneously leads a company documented as sourcing from Chaco deforestation, sits on the board of the distributor marketing that charcoal as sustainable, and presides over the industry body lobbying Paraguay's forestry regulators.

6. Corporate Structures: Bricapar S.A., EFISA, and Madexport Paraguay S.A.

1. BRICAPAR S.A.

Charcoal production & export

Paraguay's largest charcoal exporter, producing lumpwood charcoal and briquettes from native Chaco hardwoods at facilities including Teniente Ochoa. Part-owned by Spanish distributor Ibecosol (26%) and the Jiménez Gaona family (~56%), with ties to a former government minister currently under indictment.

Bricapar Corporate Structure Analysis: Full PDF (105 KB)

2. EFISA (Emprendimientos Forestales e Industriales S.A.)

Forestry, sawmilling & biomass

Vertically integrated forestry company claiming 100% plantation eucalyptus, controlled 75% by Forest International Holdings Ltd. (BVI), a vehicle of the German Winkler family's OMEX agribusiness empire. Positions itself for carbon markets but lacks independent verification of sustainability claims.

EFISA Corporate Structure Analysis: Full PDF (90 KB)

3. Madexport Paraguay S.A.

Sawmilling & wood products export

Mid-sized sawmill operation based near Coronel Oviedo processing both native hardwoods (Guatambú, Amba'y) and plantation eucalyptus. Supplies regional markets (Argentina, Uruguay) and held government contracts including emergency housing materials for SEN. The mixed native/plantation sourcing raises traceability questions.

Madexport Corporate Structure Analysis: Full PDF (88 KB)

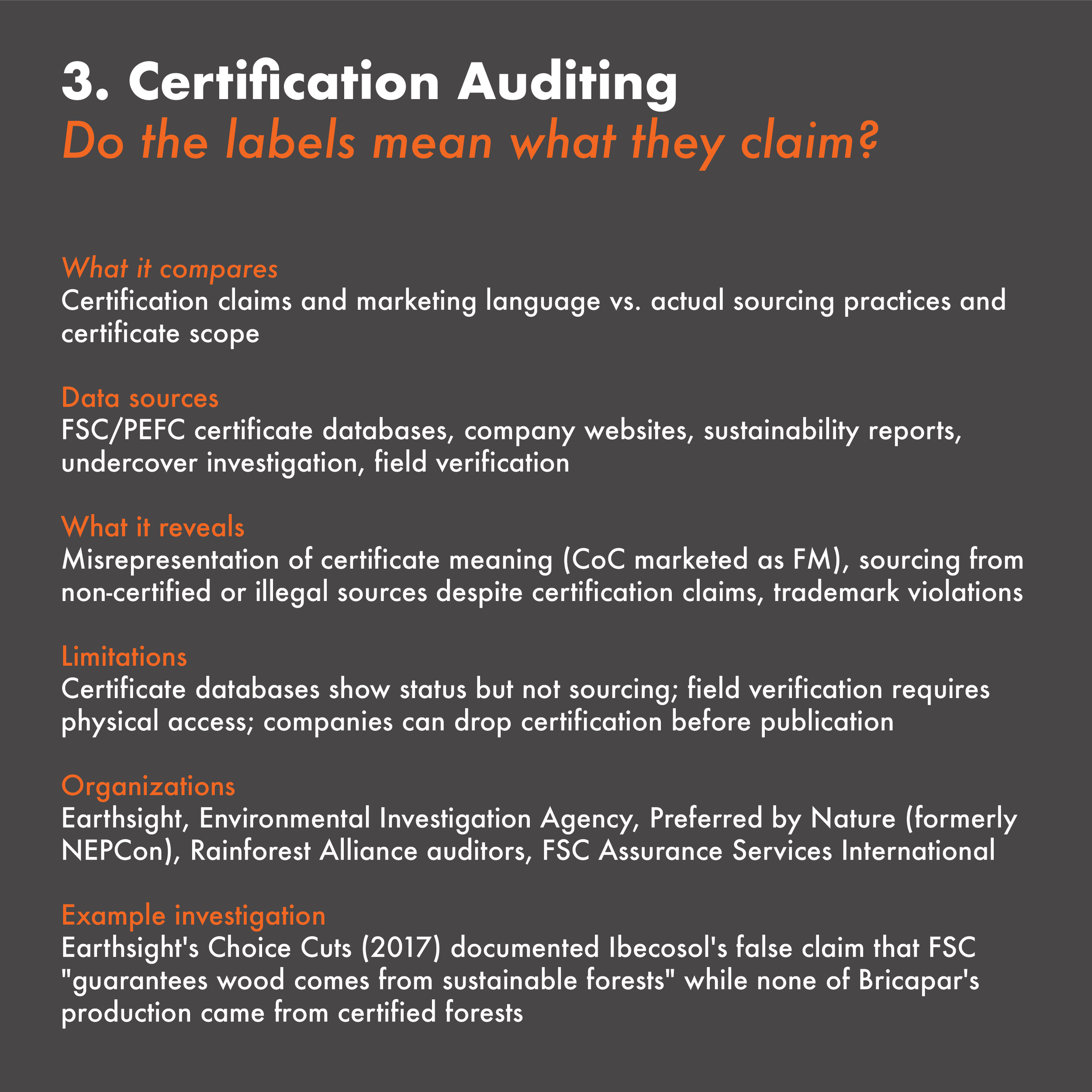

Figure 16. This table distinguishes between Chain of Custody and Forest Management certification, which is central to understanding how Ibecosol marketed Bricapar's charcoal as sustainable without any of it coming from certified forests. Terms like "beneficial owner," "holding company," and "cross-directorship" also provide the framework for understanding why EFISA's BVI registration obscures accountability and why Jiménez Gaona's simultaneous roles constitute a structural conflict of interest.

Three Key Figures: Where Accountability Lands

Figure 17. Stephan Bogislav Winkler

OMEX is a significant multinational agribusiness group, and EFISA represents just one piece of the Winkler family's broader portfolio. The choice to register Forest International Holdings in the British Virgin Islands appears deliberate, limiting disclosure of ownership details, financial flows, and any other Latin American forestry assets the family may control. EFISA markets itself as the sustainable alternative to competitors, claiming 100% plantation sourcing with no native forest extraction, but this claim has not been independently verified. The company is also positioning itself for carbon credit investors, and if its sustainability claims prove to be overstated, there is potential for greenwashing at scale. Unlike executives at comparable agribusiness firms, Winkler maintains no public profile—consistent with the limited disclosure strategy evident in EFISA's BVI registration.

Figure 18. Manuel Jiménez Gaona Arellano

Serves simultaneously as President of BRICAPAR, Paraguay's largest charcoal exporter; Director of Ibecosol, its European distributor; and President of FEPAMA, the national timber federation that lobbies government regulators. This triple role means he leads a company documented as sourcing from Chaco deforestation, sits on the board of the distributor using sustainability certifications to market that charcoal, and presides over the industry body shaping Paraguay's forestry policy. His family controls 56% of BRICAPAR, with his brother Ramón—former Minister of Public Works, currently under indictment—holding 25%.

Figure 19. Guillermo Vega de Seoane Luca de Tena

Serves as CEO of Ibecosol, the Spanish company that distributes BRICAPAR's charcoal across Europe and holds a 26% ownership stake in the Paraguayan producer. In a 2013 interview, he described the two companies as "practically the same company," and in 2017 confirmed to an Earthsight investigator that charcoal sold in Lidl, Aldi, and Carrefour stores originates from BRICAPAR's Teniente Ochoa facility. Ibecosol holds FSC and PEFC Chain of Custody certificates under his leadership, yet Earthsight found the company's website falsely claimed these certifications guarantee sustainable sourcing when none of BRICAPAR's production comes from FSC-certified forests. He also chairs the European Solid Fuels and Firelighter Technical Committee, giving him direct influence over industry standards governing charcoal certification across the continent.

Earthsight Paraguay Investigation #2

Grand Theft Chaco (September 2020)

Leather, Cattle Ranching & Indigenous Rights

Figure 20. This investigation revealed how parts of the Chaco inhabited by the indigenous Ayoreo Totobiegosode had been illegally cleared by ranching firms found to be in the leather supply chains of European car giants BMW and Jaguar Land Rover. The report documented 3,283 hectares of illegal clearance within recognized indigenous territory, land protected by Inter-American Commission of Human Rights measures since 2016. The Ayoreo Totobiegosode are the last isolated indigenous peoples living anywhere in the Americas outside the Amazon rainforest. Despite the findings, Paraguayan authorities took no action, prompting an open letter from NGOs and a European Parliament member.

Process Note

This is where progress slowed. Geospatial analysis was no longer possible without ground-truthing, and INFONA publishes very little permit data online. I wanted to look deeper into specific companies, so I gave Claude my compiled spreadsheets of sawmills, wood exporters, and charcoal exporters. Claude cross-referenced corporate registry data to map ownership chains, identified shared directorships revealing conflicts of interest, traced offshore registrations to understand where disclosure ends, and audited the gap between certification claims and actual certificate scope. Three companies emerged as warranting deeper investigation: Bricapar, EFISA, and Madexport.

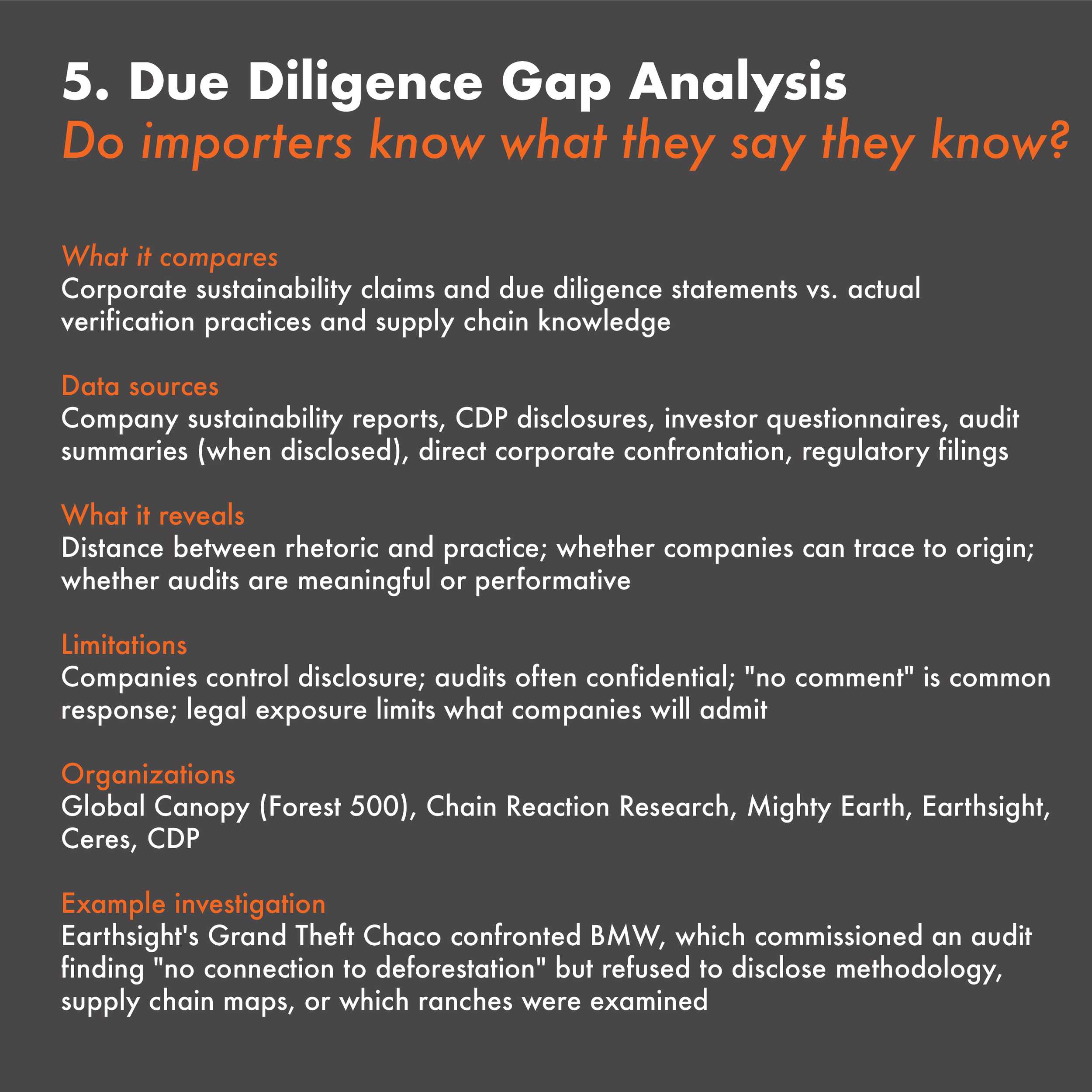

Using sources including Earthsight's undercover investigations, UK Companies House, Spanish Mercantile Registry, Paraguay's government procurement portal, FSC/PEFC certificate databases, LinkedIn, and corporate websites, Claude created three corporate structure analysis reports (linked above). I also returned to Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco to study the investigative methods its reporters employed when reaching the end of a paper trail—how they moved from tracking satellite imagery to following cattle shipment trucks on the ground, identifying slaughterhouses, tracking FSC Chain of Custody certificates, to evidence of companies making false marketing claims.

Furthering an investigation of these three companies would indeed require a level of inquiry that I couldn’t do from a desk: verify EFISA's plantation claims through site visits, access INFONA's permit database to cross-reference company filings with actual authorizations, obtain beneficial ownership records from the British Virgin Islands, or review the full case file underlying Ramón Jiménez Gaona's indictment. The opacity is structural—BVI registration, INFONA's unpublished data, certification systems that verify handling rather than origin—all diffuse accountability across jurisdictions. A researcher with subpoena power, a journalist with sources inside Paraguay's regulatory agencies, or an investigator with resources for field verification could answer questions I can only pose.

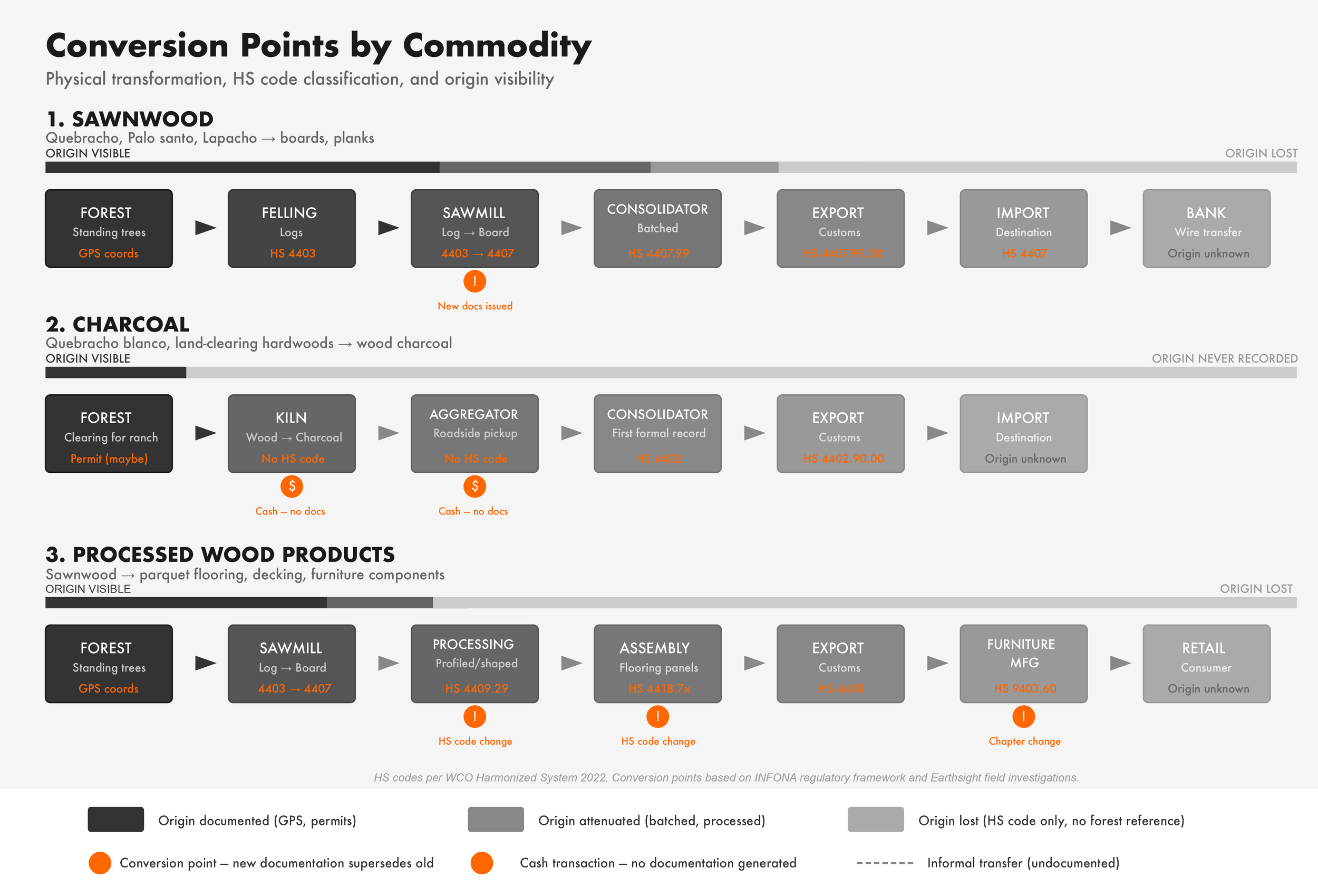

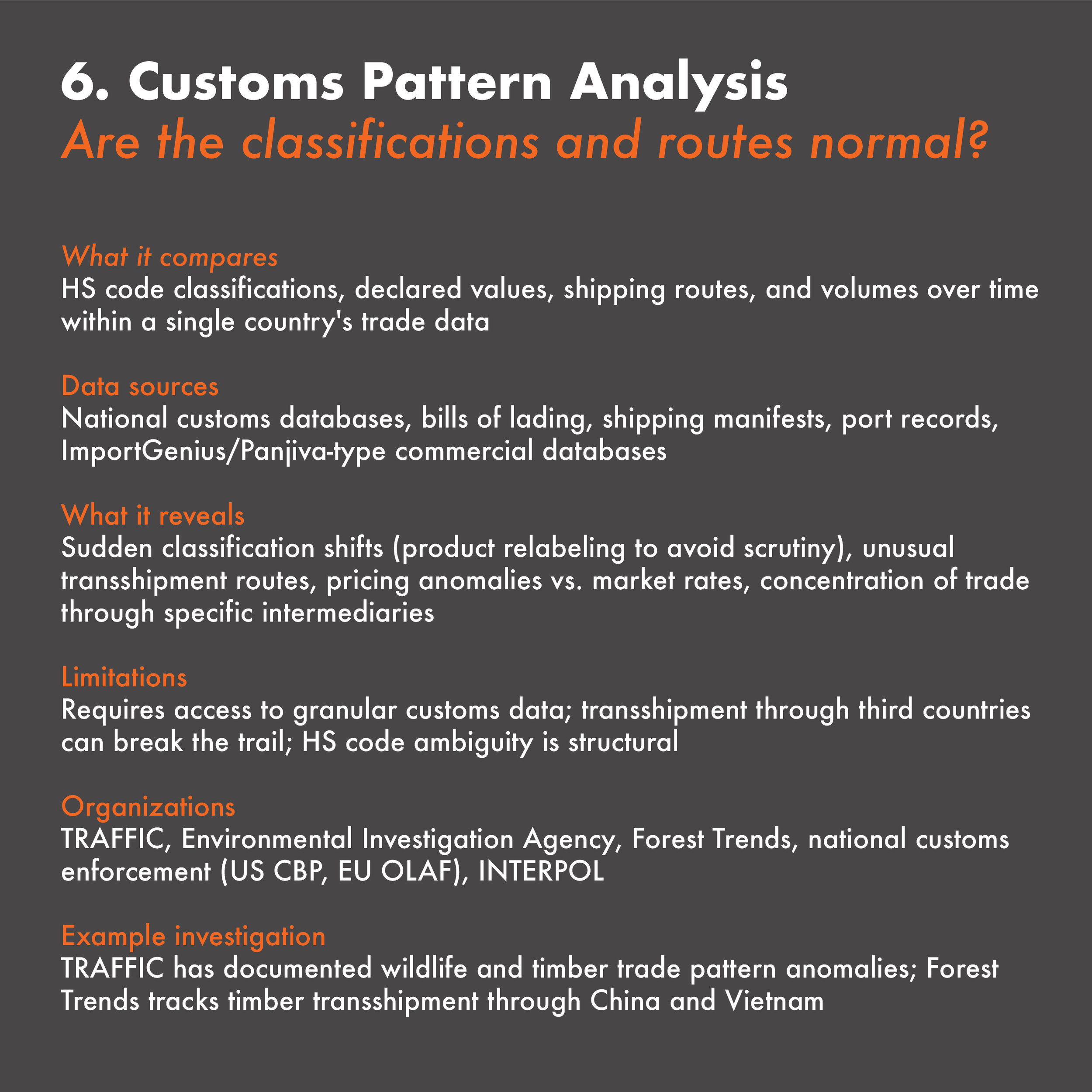

7. Conversion Points, Money Laundering & SEPRELAD

The actual mechanics of money laundering involve not one washing but a series of conversions: cash becomes deposit, deposits fund wire transfers, wire transfers purchases assets, assets generate income that appears legitimate. Timber follows a parallel logic. A standing tree in the Chaco is not a tradeable commodity; it must be converted—into a felled log, then sawnwood or charcoal, then an HS-coded export, then a payment received through the banking system. Each conversion is both physical and administrative. The physical transformation changes the material; the administrative transformation changes the paperwork. What makes timber laundering possible is that each administrative conversion creates a new document that supersedes the last. The transport guide that accompanied logs from forest to mill is not attached to the export declaration that accompanies sawnwood to the buyer.

Paraguay has the institutional architecture to monitor both ends of this chain: INFONA regulates forestry permits at the origin; SEPRELAD (the national Financial Intelligence Unit) monitors suspicious transactions at the financial endpoint through designated "obligated subjects," primarily banks. But timber companies, sawmills, and charcoal producers are not within SEPRELAD's purview. The result is a jurisdictional gap at precisely the consolidation points where origin is obscured. Banks bear the compliance burden but are positioned where they can only see cleaned documentation: an invoice, a bill of lading, an HS code. They cannot see whether the underlying wood was legally harvested. In the charcoal sector—the commodity Earthsight identified as combining "maximum deforestation impact with minimum traceability"—the gap is total: cash transactions at kiln and roadside mean proceeds may never enter the banking system at all. The oversight architecture monitors what it can see; what it cannot see is where the laundering happens.

“The Secretariat for the Prevention of Laundering of Money or Assets (SEPRELAD) — the financial intelligence unit (FIU) — is Paraguay’s AML authority. SEPRELAD has Minister-level leadership that reports directly to the President....Weak controls in the financial sector, porous borders, bearer bonds, casinos, unregulated exchange houses, lax or no enforcement of cross-border transportation of currency and negotiable instruments disclosures, ineffective and/or corrupt customs inspectors and police, trade-based value transfer, underground remittance systems, and minimal enforcement activity for financial crimes allow money launderers, transnational criminal syndicates, and possibly terrorism financiers to take advantage of Paraguay’s financial system”

Figure 21. Each commodity track shows the physical and administrative transformations through which forest products pass before reaching international markets, with corresponding HS code classifications. Origin visibility (indicated by grayscale gradient) declines at each conversion point; in the charcoal track, cash transactions at kiln and aggregator stages mean origin is never recorded at all.

“The academic literature on tradebased money laundering (TBML) has highlighted its intricate nature and the many factors contributing to its complexity. Firstly, the volume of global trade presents a challenge for conducting transactional due diligence, therefore hindering the detection of suspicious transactions. Furthermore, the absence of standardized associated trade data, comprising language and format variations, impedes reliance on trade anomalies as an effective detection mechanism. Secondly, the diversity of goods involved in trade transactions coupled with limited expertise among customs officers concerning each specific commodity, make it difficult to identify abnormalities in trade patterns.”

Figure 22. INFONA and MADES regulate forestry permits at the point of origin; SEPRELAD monitors financial transactions through obligated subjects—primarily banks—at the point of payment. The timber sector itself (sawmills, consolidators, aggregators) falls into a jurisdictional gap where no entity bears AML reporting obligations. By the time payments reach banks, origin information has been obscured through successive conversion points; in the charcoal sector, cash transactions may bypass the banking system entirely.

“The central gateway for introducing illegal timber into the legal supply chain is at the point of processing, predominantly at the sawmill. Efforts to prevent the mixing and mislabelling of timber products must therefore concentrate on increasing transparency at the sawmills as well as both upstream and downstream along the supply chain...Transport passes and timber labels ought to verify the legality of the timber in transit. However, the common practice of simply forging the necessary documents or issuing false labels has made this control system extremely fallible.””

Process Note

At this point, I found that I needed to back off the specific trail of Bricapar, EFISA, and Madexport in order to look more broadly at how jurisdictional oversight mapped beside lumber conversion points. I mapped physical and administrative conversion points across three commodity tracks: sawnwood, charcoal, processed wood. To analyze SEPRELAD's jurisdictional scope, I employed Claude Ai chatbot to review Law 1015/97 (AML framework), its 2009 amendment (Law 3783/09), and SEPRELAD's published list of sujetos obligados. Claude also referenced GAFILAT's 2022 Mutual Evaluation Report, US State Department INCSR reports (2016, 2020), US Treasury's 2023 Paraguay Economic Crimes Team evaluation, and the IMF's 2008 Detailed Assessment Report on AML. The result is a flow chart (Figure 22 Consolidation Nodes and Jurisdictional Oversight) that reveals an "inverse oversight" pattern: forestry regulation at origin, financial regulation at endpoint, jurisdictional gap in between. General literature on money laundering mechanics informed my framing of timber supply chain transformations as parallel to financial conversion processes. Next steps would include a SEPRELAD data request on forestry-related STRs (if any exist) and possibly getting on the ground to trace the cash economy at charcoal aggregation points, which would be a major challenge and expense.

8. Making The Record Legible & A Final Note

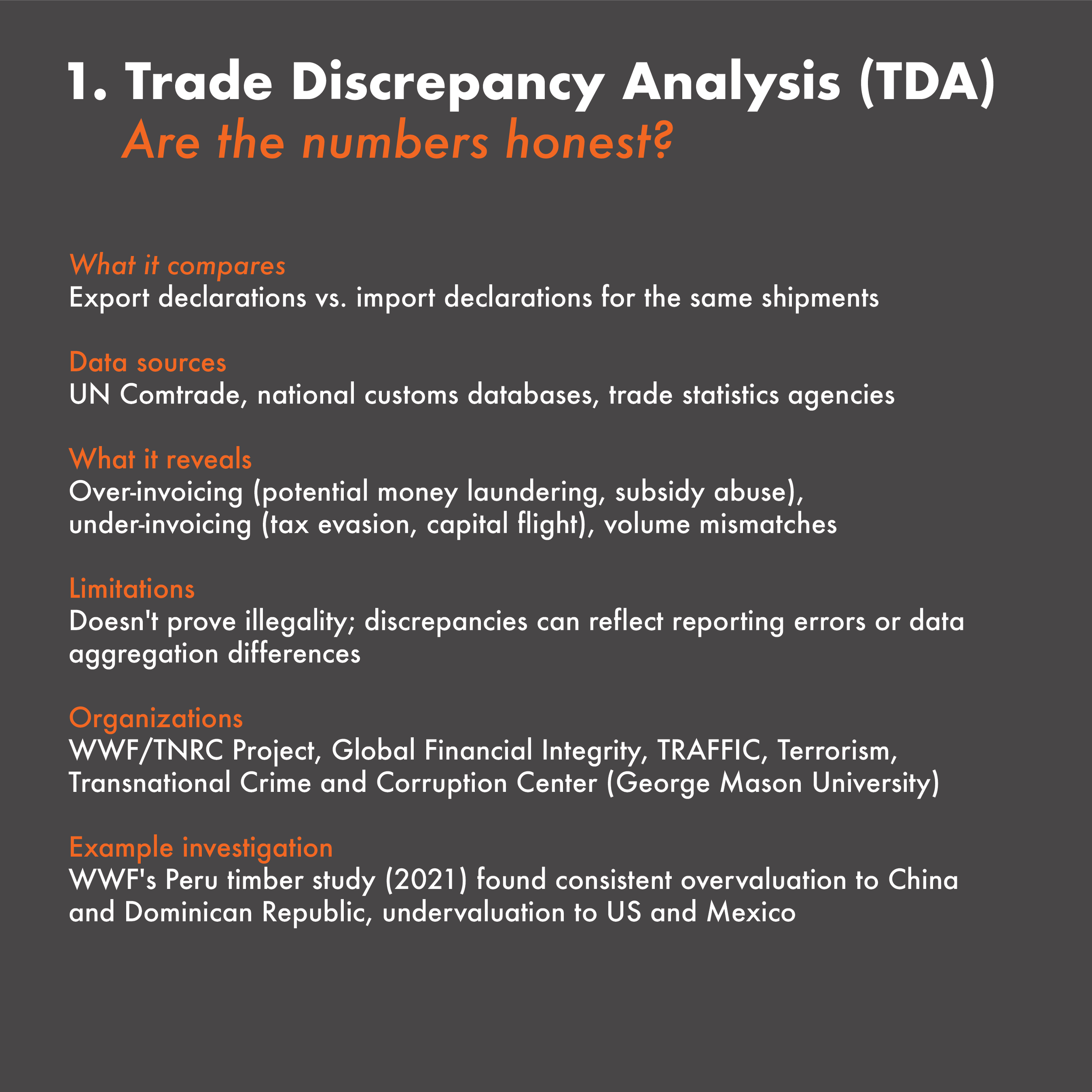

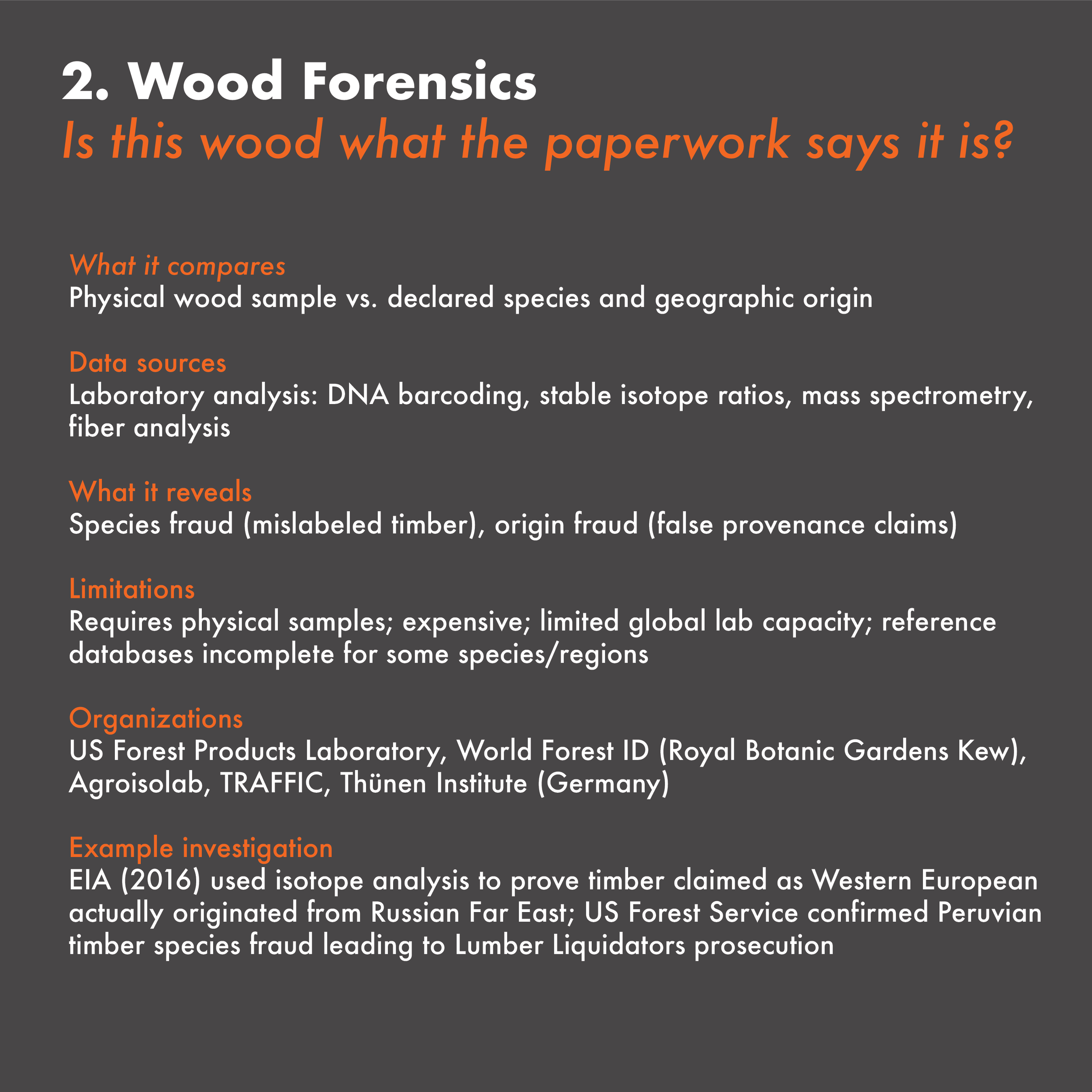

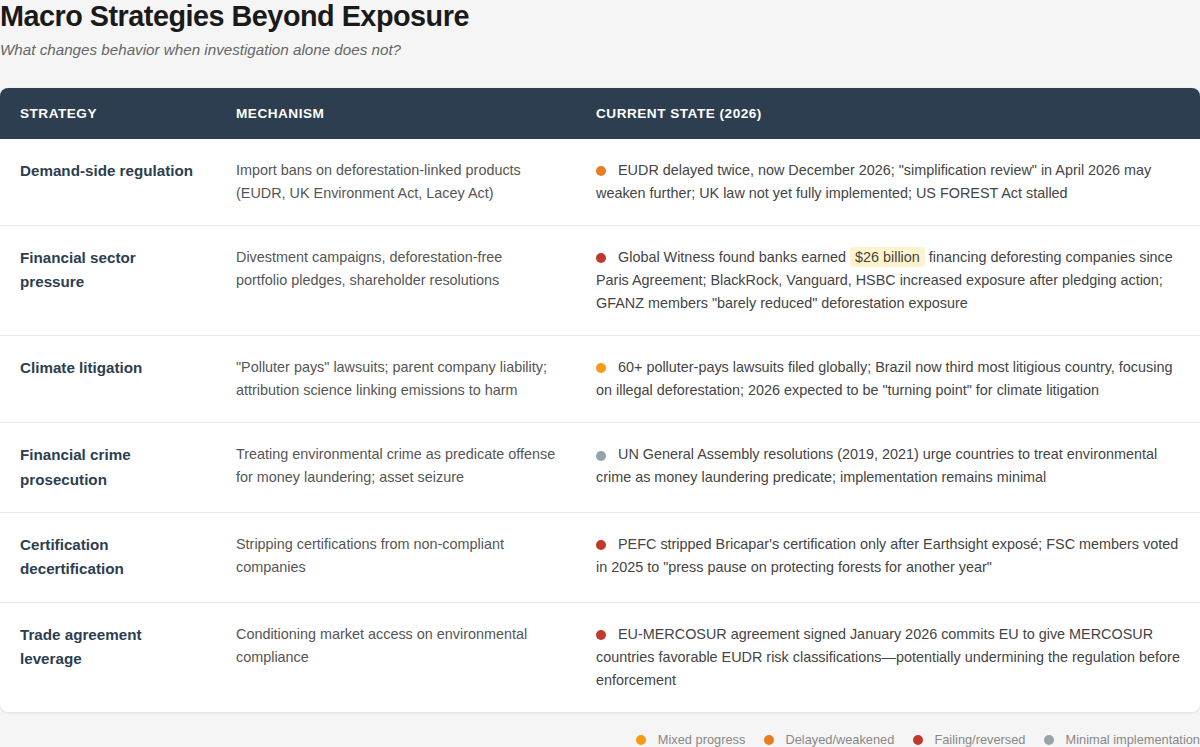

Investigative work like Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco or Choice Cuts performs a necessary function: it establishes the evidentiary record. Without documentation, there is nothing to enforce, nothing to litigate, nothing to divest from. The six detection methods outlined in this chapter—trade discrepancy analysis, wood forensics, certification auditing, due diligence gap analysis, beneficial ownership research, customs pattern analysis—are the infrastructure of accountability.

But infrastructure requires political will to operate. The gap between what investigators can document and what regulators will enforce has widened in 2026, not narrowed. Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco II opens with a blunt admission: "One year on, little has changed." Paraguayan authorities did not investigate the illegalities exposed. Leather from implicated firms continued to flow to European tanneries. BMW commissioned an audit and found "no connection to deforestation," but refused to disclose methodology. The investigation generated headlines, prompted a Paraguayan Senate inquiry, and documented what should have been prosecutable violations. None of it altered the underlying dynamic.

This raises a question the report cannot avoid: what, beyond exposure, actually changes behavior? Voluntary pledges have proven hollow. Mandatory regulations have been delayed and diluted. Financial institutions that pledged to eliminate deforestation from portfolios by 2025 increased their exposure instead. Moreover, even if demand-side regulations were enforced as designed, they would govern only a fraction of the market: the EUDR covers EU imports, but deforestation-linked products can simply flow to China, the Gulf states, or other markets with no equivalent requirements—a phenomenon known as leakage. With the United States dismantling its environmental regulatory architecture and withdrawing from international climate cooperation, the destinations for leaked commodities are expanding, not contracting. The question is whether this moment represents a temporary setback or a structural collapse of the accountability framework that investigators have spent decades building. The answer depends on whether the evidentiary record they've created can survive the current political environment long enough to be acted upon when conditions change, or whether the forests will be gone first.

1. Trade Discrepancy Analysis Resources

UN Comtrade Database

Global trade data by HS code, country, year—foundation for TDA

comtradeplus.un.org

Global Financial Integrity TDA Reports

Methodological examples of trade misinvoicing analysis across sectors

gfintegrity.org

UNCTAD Trade Analysis Tools

Statistical tools for analyzing bilateral trade flows

unctad.org

TradeMap (ITC)

Trade statistics and market access

informationtrademap.org

2. Wood Forensics Resources

World Forest ID

Global reference database for timber identification; partnership with Royal Botanic Gardens Kew

worldforestid.org

US Forest Products Laboratory

Forensic species identification services; reference collections

fpl.fs.usda.gov

TRAFFIC Timber ID Resources

Guides for identifying CITES-listed timber species

traffic.org

Double Helix Tracking Technologies

Commercial timber DNA verification services

doublehelixtracking.com

3. Certification Auditing Resources

FSC Certificate Database

Searchable database of all FSC-certified entities; shows certificate scope and status

info.fsc.org

PEFC Certificate Search

Equivalent database for PEFC chain of custody and forest management certificates

pefc.org

Preferred by Nature

Sourcing HubRisk assessments by country and product; certification gap analysis

preferredbynature.org

Earthsight Investigation Reports

Methodological examples of certification auditing in practice

earthsight.org.uk

4. Beneficial Ownership Research Resources

ICIJ Offshore Leaks Database

Searchable database from Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Pandora Papers

offshoreleaks.icij.org

OpenCorporates

Largest open database of corporate registrations worldwideopencorporates.com

Open Ownership Register

Beneficial ownership data from countries with public registers

openownership.org

Aleph (OCCRP)

Cross-referenced database of corporate records, leaks, and public

filingsaleph.occrp.org

Sayari Graph

Commercial tool for corporate network mapping and sanctions

screeningsayari.com

5. Due Diligence Gap Analysis Resources

Forest 500 (Global Canopy)

Annual assessment of deforestation policies and practices for 500 companies most exposed to forest-risk supply chains

forest500.org

Chain Reaction Research

Financial risk analysis of companies linked to deforestation

chainreactionresearch.com

CDP Forests Questionnaire

Corporate disclosures on forest-related risks and due diligence

cdp.net

Trase

Supply chain mapping platform linking commodities to traders

trase.earth

Mighty Earth Rapid Response Reports

Real-time monitoring of corporate deforestation

linksmightyearth.org

6. Customs Pattern Analysis Resources

ImportGenius / Panjiva

Commercial databases of bills of lading and shipping manifests

importgenius.com / panjiva.com

Global Trade Atlas

Detailed customs data by HS code, country, company

globaltradetracker.com

TRAFFIC Trade Monitoring Resources

Guides for analyzing wildlife and timber customs

datatraffic.org

WCO HS Code Database

Official Harmonized System classifications and explanatory notes

wcoomd.org

EU TARIC Database

EU customs classification and tariff information

ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs

Figure 23. Beyond exposure, six macro strategies exist to change behavior in deforestation-linked supply chains: demand-side regulation (import bans like the EUDR), financial sector pressure (divestment and portfolio pledges), climate litigation (polluter-pays lawsuits), financial crime prosecution (treating environmental crime as a money laundering predicate), certification decertification (stripping non-compliant companies of sustainability labels), and trade agreement leverage (conditioning market access on environmental compliance). As of early 2026, all six are weakening, stalled, or actively undermined: the EUDR has been delayed twice and faces further dilution, financial institutions that pledged to eliminate deforestation by 2025 instead increased their exposure, certification bodies have voted to pause enforcement, and the EU-MERCOSUR agreement commits Europe to favorable risk classifications for the very countries driving deforestation. Only climate litigation shows mixed progress, with 60+ polluter-pays lawsuits filed globally and 2026 expected to be a turning point. The gap between what investigators can document and what regulators will enforce has widened, not narrowed.

A Final Note

I spent less than two weeks on this report. Using AI research and QGIS geospatial analysis tools, I was able to approach a supply chain analysis that would previously have required collaboration and a time commitment. This is not a boast; it's a data point about what's now possible. The infrastructure of accountability I've described in this chapter—trade discrepancy analysis, wood forensics, certification auditing, beneficial ownership research—are not inaccessible. They are underused because the political will to apply them has collapsed. What has not collapsed is the capacity of a single researcher, working remotely, to assemble an evidentiary record and make it legible.

I see this kind of investigative work as service. Sometimes public servants need to keep their heads down and persist in the rigorous work of due diligence without calibrating their process or goals based on outcomes of justice. Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco II documented that one year after their exposé, nothing had changed, but reform was never the only metric. The question is also: who heard? How far did the information travel? Into which conversations did it enter?

Environmental messaging has long been produced for highly educated, like-minded audiences, a group economist Thomas Piketty might call the "Brahmin left," referring to educated elites who share cultural values but have little connection to the economic struggles of the majority. Reports like this one here are rigorous, but the potential readership is unbelievably narrow. As a researcher, I am proud to contribute to discourses that value nuance and complexity. As a storyteller, I believe the same evidentiary record must be adapted for audiences who don't read forty-page PDFs: short-form video in Spanish, Portuguese and Guaraní for Paraguayan and MERCOSUR audiences, equivalent content for demand-side consumers in Europe and China, formatted for the attention economy: vertical, narrated, frequent. The goal is not necessarily to trigger prosecution but to populate niche online conversations across geographical nodes of the supply chain. Latent pressure, distributed widely, waiting for leverage points that don't yet exist.

This requires humility. The changes in the geopolitical and information landscapes demand constant renegotiation and nimble pivots. This also requires muscle and tenacity: there are no knock-out punches, only thousands of jabs. I do not know what will work, but I believe the current moment is not permanent. I expect that in my lifetime, Paraguay will transition from rapid deforestation to a period of introducing sustainability technologies aimed at preserving beef-cattle revenues. I believe this not from optimism about justice but from a clear-eyed assessment of what's happening: we are close to eradicating primary forest in Paraguay. Deforestation will not stop because of a change in conservation attitudes. It will stop because the forest is gone. At that point, the cattle-beef-leather industries will face economic challenges caused by a degrading environment, and it will be profit—not justice—that drives the introduction of sustainable technologies.

This is grim. But it is also a prediction that positions the work differently. The evidentiary record I've compiled—the corporate structures, the conversion points, the financial pathways, the detection methods—will matter more, not less, when the transition comes. Someone will need to explain how it happened, who profited, and what was lost. Someone will need to have documented the names, the mechanisms, the choices that were made. I have endeavored to contribute to that record here. Whether this work can be expanded for use in a courtroom or a short video that reaches someone in Asunción, I hope to contribute regardless. What I can do is make the information exist, make it legible, and make it available for whatever comes next.

9. References

WRITTEN SOURCES

—Baumann, Matthias, et al. “Land-Use Competition in the South American Chaco.” Land Use Competition: Human-Environment Interactions, edited by Jörg Niewöhner et al., vol. 6, Springer, 2016, pp. 215–229, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33628-2_13

—Blackmore, Emma, Danning Li, and Sara Casallas. Sustainability Standards in China–Latin America Trade and Investment: A Discussion. International Institute for Environment and Development, May 2013, https://www.iied.org/16544iied

—Council on Foreign Relations. "Mercosur: South America's Fractious Trade Bloc." Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/backgrounders/mercosur-south-americas-fractious-trade-bloc. Accessed 25 Jan. 2026.

—Da Ponte, Emmanuel, et al. “Understanding 34 Years of Forest Cover Dynamics across the Paraguayan Chaco: Characterizing Annual Changes and Forest Fragmentation Levels between 1987 and 2020.” Forests, vol. 13, no. 1, 2022, article 25, https://doi.org/10.3390/f13010025

—"Deforestation Rates Slashed in Paraguay." WWF, 2006, www.wwfca.org/en/?79260%2FDeforestation-rates-slashed-in-Paraguay.

—Durand-Morat, Álvaro. “Agricultural Production Potential in Southern Cone.” Choices, vol. 34, no. 3, 3rd Quarter 2019, pp. 1–7. Agricultural & Applied Economics Association, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26964934

—Earthsight. "Choice Cuts: EU & US BBQs Fuelled by Paraguay's Deforestation Crisis." Earthsight, 6 July 2017, www.earthsight.org.uk/news/investigations/choice-cuts-paraguay-2017-bricopar-supermarkets.

—Earthsight. Grand Theft Chaco. Earthsight, 30 Sept. 2020, https://www.earthsight.org.uk/grandtheftchaco-en

—Earthsight. "Nearly a Quarter of Chaco Deforestation Potentially Illegal, Says Paraguay Enforcement Agency." Earthsight, 2019, www.earthsight.org.uk/news/idm/paraguay-nearly-quarter-gran-chaco-deforestation-potentially-illegal-infona.

—Earthsight. "Paraguayan Authorities Complicit in Illegal Razing of Country's Forests by EU-Linked Agribusiness." Earthsight, 2022, www.earthsight.org.uk/news/analysis/paraguayan-authorities-complicit-in-illegal-razing.

—Earthsight. "Paraguay's Looted Lands." 2020, www.earthsight.org.uk/news/investigation-analysis-paraguays-looted-lands.

—Felter, Claire, and Danielle Renwick. "Mercosur: South America's Fractious Trade Bloc." Council on Foreign Relations, www.cfr.org/backgrounder/mercosur-south-americas-fractious-trade-bloc. Accessed 26 Jan. 2026.

—Gabay, Aimee. "Report Links Financial Giants to Deforestation of Paraguay's Gran Chaco." Mongabay, 13 Apr. 2023, news.mongabay.com/2023/04/report-links-financial-giants-to-deforestation-of-paraguays-gran-chaco/.

—Gilmour, Paul, et al. "Trade-Based Money Laundering: A Systematic Literature Review." Journal of Accounting Literature, vol. 47, no. 5, 2025, doi.org/10.1108/JAL-10-2023-0179.

—Global Witness. Cash, Cattle and the Gran Chaco: How Financiers Turned a Blind Eye to Paraguay’s Deforestation Crisis. Global Witness, 30 Mar. 2023, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/cash-cattle-and-the-gran-chaco-how-financiers-turned-a-blind-eye-to-paraguays-deforestation-crisis/

—Huang, Chengquan, et al. "Rapid Loss of Paraguay's Atlantic Forest and the Status of Protected Areas — A Landsat Assessment." Remote Sensing of Environment, vol. 106, no. 4, 2007, pp. 460–466, doi:10.1016/j.rse.2006.09.016.

—Inside Paraguay’s Forestry Boom: How Exports Hit Historic Highs in 2025. (2025, published online). The Asunción Times. Retrieved 2026, from https://asunciontimes.com/paraguay-news/economy/forestry-exports-reach-new-highs-in-paraguay/

—IUCN NL. "Tackling Uncontrolled Deforestation in Paraguay by Improving Landscape Planning." IUCN NL, 1 June 2019, www.iucn.nl/en/story/tackling-uncontrolled-deforestation-in-paraguay/.

—Kaulen, Annika. “Systematics of Forestry Technology for Tracing Timber Supply Chains.” Forests, vol. 14, no. 9, 2023, article 1718.

—Kimbrough, Liz. “Indigenous Group Fights Cattle Onslaught, Defends Uncontacted Relatives in the Gran Chaco.” Mongabay, 6 May 2022, https://news.mongabay.com/2022/05/indigenous-group-fights-cattle-onslaught-defends-uncontacted-relatives-in-the-gran-chaco/

—Milán, María José, Elizabeth González, and Feliu López-i-Gelats. “The Livestock Frontier in the Paraguayan Chaco: A Local Agent-based Perspective.” Environmental Management, vol. 73, no. 6, 2024, pp. 1231–1246, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-024-01957-7

—Milán, María José, and Elizabeth González. “Beef–cattle ranching in the Paraguayan Chaco: Typological approach to a livestock frontier.” Environment, Development and Sustainability, vol. 25, no. 6, 2023, pp. 5185–5210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02261-2

—Muñoz, Banyeliz. "European Agriculture Seen as Main Obstacle to EU–Mercosur Trade Deal." UPI, 23 Jan. 2026, www.upi.com/Top_News/World-News/2026/01/23/latam-european-agriculture-eu-mercosur/3241769183600.

—Pardo, Camilo. The International Links of Peruvian Illegal Timber: A Trade Discrepancy Analysis. World Wildlife Fund, Targeting Natural Resource Corruption (TNRC) Project, May 2021, www.worldwildlife.org/publications/the-international-links-of-peruvian-illegal-timber-a-trade-discrepancy-analysis.

—le Polain de Waroux, Yann, et al. “Land-use policies and corporate investments in agriculture in the Gran Chaco and Chiquitano.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, vol. 113, no. 15, 2016, pp. 4021–4026, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602646113

—Reuters. "Analysis: Paraguay on Track for Record Soy Crop, but Low River Levels Slow Exports." U.S. News & World Report, April 18, 2024. https://money.usnews.com/investing/news/articles/2024-04-18/analysis-paraguay-on-track-for-record-soy-crop-but-low-river-levels-slow-exports

—Risso, Melina, et al. Follow the Money: How Environmental Crime Is Handled by Anti-Money Laundering Systems in Brazil, Colombia, and Peru. Igarapé Institute, 2023, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16745983

—Ross, Gregory. "U.S. and China Spar for Influence on the Paraguay-Paraná River System." Americas Quarterly, 5 June 2025, www.americasquarterly.org/article/u-s-and-china-spar-for-influence-on-the-paraguay-parana-river-system/.

—Schorr, Bettina, and Jan Schubert. "Illegal Logging, Timber Laundering and the Global Illegal Timber Trade." Organized Crime and Illicit Trade, edited by Günther Maihold et al., Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik (SWP), 2022, pp. 97–122.

—"Tropical Deforestation in Paraguay and Our BBQ." openDemocracy, www.opendemocracy.net/en/democraciaabierta/tropical-deforestation-for-charcoal-in-paraguay-to-fuel-your-bbq/.

—Vidal, John. "Clamping Down on Logging in Brazil Moves It to Paraguay." The Ecologist, 20 Nov. 2009, theecologist.org/2009/nov/20/clamping-down-logging-brazil-moves-it-paraguay.

—World Bank. (2020). A Forest’s Worth: Policy options for a sustainable and inclusive forest economy in Paraguay (Paraguay Country Forest Note). World Bank. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/34988

GEOSPATIAL DATASETS

—Benden, P. (2022). Global Shipping Lanes [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6361763

—Dinerstein, Eric, et al. "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm." BioScience, vol. 67, no. 6, June 2017, pp. 534–45, doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix014.

—Dirección General de Estadísticas, Encuestas y Censos (DGEEC). Paraguay Administrative Boundaries, Level 0–2. 2020. Distributed by OCHA Humanitarian Data Exchange, data.humdata.org/dataset/cod-ab-pry.

—Fagan, Matthew E., et al. Pantropical Tree Plantation Expansion (2000–2012). Global Forest Watch, 2022, data.globalforestwatch.org/content/pantropical-tree-plantation-expansion-2000-2012.

—Global Forest Watch. 2026. “Integrated Deforestation Alerts – Paraguay Tiles.” Accessed 2026-01-15.

—Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., et al. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science, 342(6160), 850–853. DOI: 10.1126/science.1244693

—International Trade Centre (ITC). 2026. “Trade Map – Paraguay Exports by HS Code.” Accessed 2026-01-15.

—LandMark: The Global Platform of Indigenous and Community Lands. 2025. Accessible at: www.landmarkmap.org.

—Leandro Parente, Lindsey Sloat, Vinicius Mesquita, Davide Consoli, Radost Stanimirova, Tomislav Hengl, Carmelo Bonannella, Nathália Teles, Ichsani Wheeler, Maria Hunter, Steffen Ehrmann, Laerte Ferreira, Ana Paula Mattos, Bernard Oliveira, Carsten Meyer, Murat Şahin, Martijn Witjes, Steffen Fritz, Žiga Malek, & Fred Stolle. (2025). Global Pasture Watch - Annual grassland class and extent maps at 30-m spatial resolution (2000—2024) (v2-beta) [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15648751

—Lehner, B., Verdin, K., & Jarvis, A. (2006). HydroSHEDS Technical Documentation. World Wildlife Fund US, Washington, DC. Data available at www.hydrosheds.org

—Li, Xuecao; Zhou, Yuyu; zhao, Min; Zhao, Xia (2020). Harmonization of DMSP and VIIRS nighttime light data from 1992-2024 at the global scale. figshare. Dataset. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9828827.v10

—MapBiomas Paraguay Project. (2023). MapBiomas Paraguay Collection 2 – Land Cover & Land Use Maps 1985–2023. São Paulo, Brazil: MapBiomas. Available at: https://paraguay.mapbiomas.org/en/descargas/

—Natural Earth Data. (version 5.1.1). Admin 0 – Countries [Vector shapefile]. Natural Earth. https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-cultural-vectors/10m-admin-0-countries/

—RAISG. 2026. “Amazon Indigenous Territories & South American Indigenous Territories Database.” Accessed 2026-01-15

—Richter, J., Goldman, E., Harris, N., Gibbs, D., Rose, M., Peyer, S., Richardson, S., and H. Velappan. 2024. “Spatial Database of Planted Trees (SDPT Version 2.0).” Accessed through Global Forest Watch on [Date]. www.globalforestwatch.org.

—Turubanova, Svetlana, et al. Primary Humid Tropical Forests, South America, 2001. University of Maryland Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD), 2018, glad.umd.edu/dataset/primary-forest-humid-tropics.

—UNEP‑WCMC & IUCN (2026). World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) [online], Cambridge, UK: UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre and International Union for Conservation of Nature. Available: https://www.protectedplanet.net

—University of Maryland (UMD). Soy Planted Area Dataset, Version 3 (2022). Distributed by Global Forest Watch (World Resources Institute).

—World Bank Group (2021). Global Shipping Traffic Density [Raster dataset]. Global Shipping Traffic Density data obtained through a partnership with the International Monetary Fund’s World Seaborne Trade Monitoring System. World Bank Data Catalog. License: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. Available at: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0037580/global-shipping-traffic-density—

![This graph from the Council on Foreign Relations shows that "China currently ranks as South America's top trading partner... and some economists predict that [China-Latin America trade] could exceed $700 billion by 2035.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/63ebe1540f59502cda54dae4/1da4bbc2-3f6c-4ad3-a065-6c6b5bcee2d4/Approaching-Deforestation-Economies-in-Paraguay_Figure-3_China-is-Mercosur%27s-Largest-Single-Export-Destination_council-on-foreign-relations.png)