THE COLLABORATIVE NONPROFIT:

Transformative Governance and Co-production Management

by Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (1.5 MB)

© 2024 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

Abstract

This article examines the Environmental Protection Agency’s Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program (TCGP) through an environmental justice lens, arguing that the program embodies a complex experiment in decentralizing federal power while navigating profound legal and structural constraints. While environmental justice traditionally involves holding institutions accountable for the equitable distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, the TCGP attempts to actualize this accountability within a fraught policy landscape—one in which race-conscious decision-making is severely restricted, even as race remains inseparable from environmental vulnerability.

The analysis focuses on the role of the National Partners East, a coalition of six nonprofit organizations that serve as the backbone support entity for the entire $600 million initiative. Through their national coordination, data stewardship, technical assistance, and storytelling efforts, the National Partners East operate within a polycentric governance system alongside Governing Councils, regional grantmakers, anchor partners, and community-based organizations. The article argues that three interconnected values—transparency, learning, and citizenship—must guide the National Partners’ approach to managing this sprawling inter-organizational network. Transparency is necessary to navigate the tensions between federal compliance and community-led priorities. Learning is essential for the adaptive governance cycles that can transform program design over time. Citizenship grounds the program in collective action, expanding participation while challenging unjust legal structures through narrative and advocacy.

Ultimately, the TCGP represents an experiment in collaborative coproduction underpinned by both bureaucratic and relational governance. If executed with rigor and intentionality, the networked management strategies outlined here may not only strengthen environmental justice outcomes at the community scale but also shape the future of federal program design—advancing systemic change from within and beyond the system.

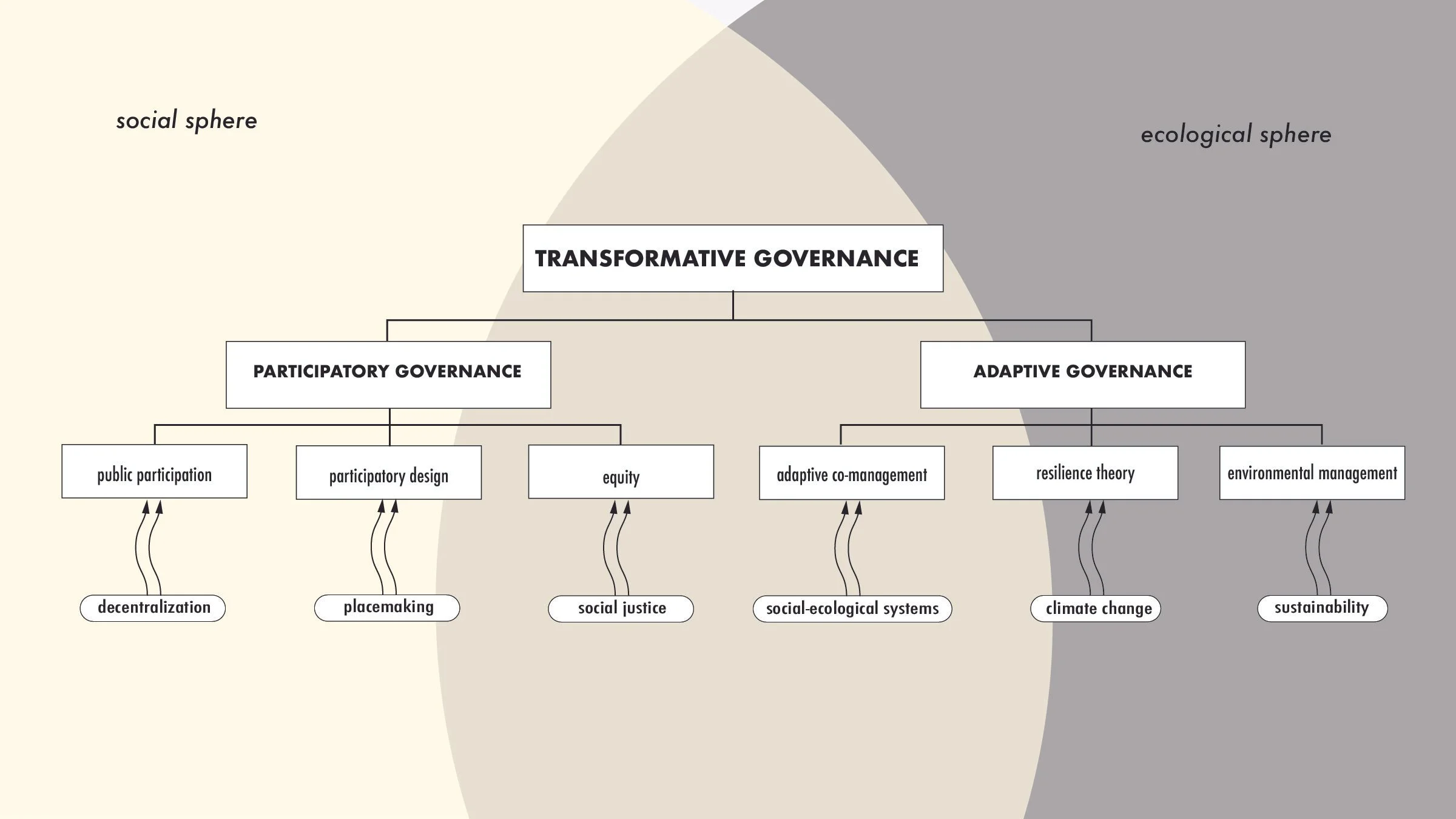

Fig 1.

This diagram by Malcolm Wyer conceives “transformative governance” as having a social lineage described by “participatory governance,” as well as an ecological lineage described by “adaptive governance.” In pursuing environmental justice, organizations must leverage decentralized, horizontal decision-making as well as social-ecological systems thinking.

Accountability

We might define environmental justice as the pursuit of accountability: holding those in power accountable for the equal distribution of environmental benefits and burdens. Environmental justice can also be understood as a lens that we can attach to a system in order to expose and upend structural inequalities. Some environmental justice practitioners develop and implement policy or programs (working inside the system,) while others work to interrogate and dismantle the logics that perpetuate inequality across legal, political, and economic systems (working outside or against the system.)

Being a government program, the EPA’s Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program (TCGP) mostly offers opportunities for working inside the system. The program and its participants are bound by US law, which now suggests that any EPA-affiliated entity that makes race-conscious decisions is in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, Chevron v. NRDC, and Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard. In fact, the Justice40 dataset—which underpins the entire TCGP—excludes race altogether as an identifier for representing “disadvantaged communities,” despite the widespread acceptance across the environmental justice community that race and environmental vulnerability are intrinsically linked.

Indeed there often exists a tension between the federal laws that direct EPA policy and the values of the nonprofit organizations tasked with implementing that policy. Across all sectors of government, agencies like the EPA are increasingly outsourcing the implementation of its programs to private organizations. Public sector outcomes—like public health and environmental services—are increasingly being produced by private nonprofit organizations. In turn, there must exist a contract of mutual accountability in partnership between government agencies and nonprofit organizations. In the case of the TCGP, while nonprofit partners are accountable to EPA policy and US law, the EPA must empower and trust its private partners to deliver public services according to the mission and values of the organization he/she represents.

This empowerment is embedded into the design of the TCGP. Ten “Governing Councils” (one for each EPA region) are comprised of community leaders and representatives from community-based organizations (CBOs.) These ten independent councils are tasked with implementing a polycentric decision-making model for overseeing the grant application and award process. This represents a radical change in how federal funds are allocated. Aimed at removing barriers between citizens and federal funds, while nurturing a bottom-up decision-making model, these Governing Councils are an attempt to relinquish power from federal bureaucrats and put it in the hands of a networked collective of regional community organizers. Additionally, the TCGP is insulated with three, horizontally-acting support entities: a group of “Anchor Partners” for each Regional Governing Council, ten regional “Technical Assistance Centers” (TCTACs,) and three coalitions of “National Partners” (East, Central, and West.)

Here I will focus on the responsibilities of the National Partners East, an inter organizational partnership formed between six nonprofits—Institute for Sustainable Communities, Urban Sustainability Director Network, Emerald Cities Collaborative, Trust For Public Land, Groundworks USA, and River Network. At the national scale, the National Partners East must implement a national website and data visualization hub that accounts for the entire $600 million of the TCGP program. At the regional scale, the National Partners East provide coordination services to the three Regional Grantmakers: Health Resources in Action (Region 1,) Fordham University (Region 2,) and Green & Healthy Home Initiative (Region 3.) At the community scale, the National Partners East provide on-demand solution services to subawardee CBOs while collaborating on storytelling projects, translating impact stores, and spearheading public relations efforts.

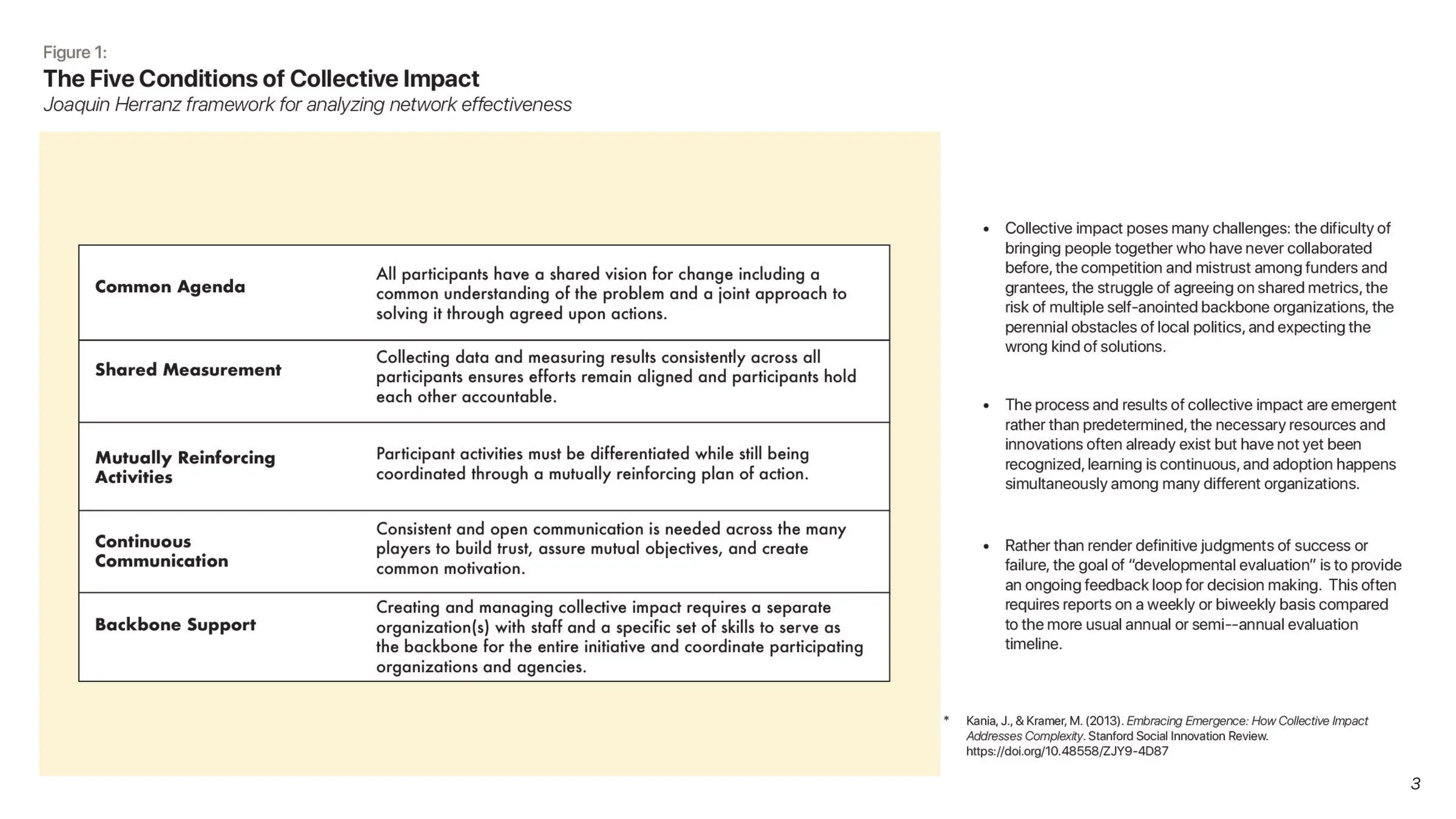

All complex networks of organizations require some coordinating entity to provide the backbone support for the entire initiative. For the TCGP, that backbone support organization is the National Partners East. In Figure 1, Joaquin Herranz outlines a framework for complex network management called “The Five Conditions of Collective Impact.” These conditions could serve as guiding principles to the National Partners East. Here, I would like to emphasize three values that should permeate all network management efforts by the National Partners: transparency, learning, and citizenship.

Fig 2.

In Joaquin Herranz’s “The Five Conditions of Collective Impact,” he develops a framework for analyzing network effectiveness based on: common agenda, shared measurement, mutually reinforcing activities, continuois communication, and backbone support.

1. Transparency

The TCGP is a new, experimental program that, if successful, could reshape the future of environmental justice government spending at a much larger scale. In this sense, all participants are saddled with the challenges of getting a new program off the ground. Indeed with the design of a transformative new management structure will come growing pains. I mentioned already the tension that comes from removing race as a data identifier. The eight categories that the EPA does employ to classify a census tract as “disadvantaged” are:

1. climate change

2. clean energy and energy efficiency

3. clean transit

4. affordable and sustainable housing

5. training and workforce development

6. remediation and reduction of legacy pollution

7. health

8. clean water infrastructure

According to the EPA, each TCGP grant must be awarded in one of these eight categories, as spatialized in the Justice40 dataset. However, the grant amounts are relatively small: between $75,000-$350,000. This begs the question: what type of meaningful clean transit project will provide community impact with $350,000? It is easy to foresee the managerial challenges connected with aligning meaningful community projects across these categories at a relatively low budget price point. Accountability is going to be a messy process.

With that in mind, the National Partners should approach their duties of accountability, measurement, and data monitoring with rigorous transparency. While it is not the responsibility of the National Partners to interfere with or to enforce any Governing Council procedure, the Governing Councils will rely heavily on the National Partners East for data and evaluation. While each Governing Councils may opt to employ quotas for the grant awards (e.g. 30% urban, 33% rural, 33% tribal,) such quotas should NOT be employed by the national website and data hub. Instead it is up to the National Partners to translate decisions made by the Governing Council with Justice40 dataset framing.

We must recognize a distinction in the operational and management structures of the regional Governing Councils versus the National Partners. The Governing Councils, comprised of representatives from diverse community organizations, are held together by historical patterns of collaboration, personal relationships, and trust. The governance structures of the National Partners, in contrast, are based on clear principal-agent contracts with the EPA. As Joaquin Herranz writes, “Government-supported networks that involve public and nonprofit agencies…are more likely to be effective when the formal control mechanisms of government are combined with the informal coordination mechanisms of interpersonal relational trust.” In order to empower Governing Councils to be independent, locally-controlled, structurally experimental, and bottom-up, the National Partners must employ a more formalized, bureaucratic and top-down management style to assure compliance with the EPA, to insulate the program from lawsuits, and to provide regional grantmakers with meaningful feedback so that decision-making processes can continually improve.

Transparency means visibility, accessibility, and consistency; as Governing Councils award funds to local CBOs, a national website should make public reports easily legible for the EPA, for all TCGP participants, and for the general public. Some sort of collective data comparisons must attempt to apply standards of measurement equally across all Governing Councils and subawardees. This needs to happen efficiently and continually. A transparent approach to data monitoring will in and of itself function as an incentive for agents to perform as promised.

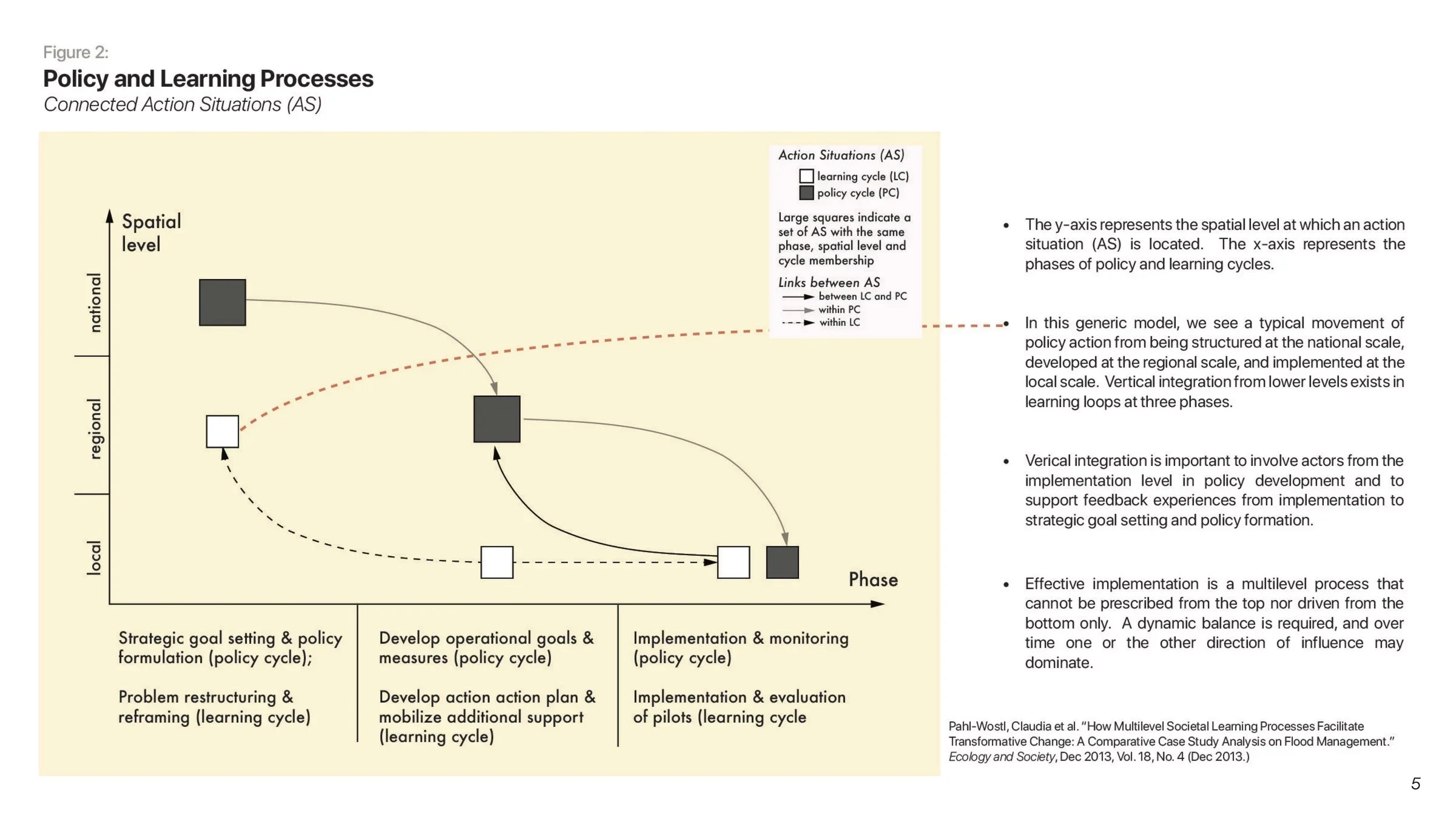

Fig 3.

This diagram by Claudia Pahl-Wostl incorporates learning processes with Action Situations (AS.) Learning loops integrate into policy action at the national scale, development at the regional scale, and implementation at the local scale.

2. Learning

Between the National Grantmaker Partners, Regional Grantmaker Partners, Anchor Partners, and Governing Councils, the TCGP is a collection of 30+ inter organizational partnerships. Each partnership (1) is an independent node of decision making within a greater polycentric network; (2) has repeated and enduring horizontal interactions with other partnerships; and (3) performs some level of horizontal support to other grant program actors such as subawardees. Ultimately the network as a whole depends on building synergy between these networked partnerships, hoping to generate outcomes that are greater than the sum of the parts.

The horizontal engagement of partners creates “learning networks” that allow best practices to be developed as a collective. Likewise, a three-year rolling grant program provides ongoing “learning loops,” in which feedback from grant cycles informs new decisions in shaping future cycles. In Figure 2 “Policy and Learning Processes,” Claudia Pahl-Wostl maps a design for how policies can improve over time through creating learning cycles. An action situation is followed by feedback and opportunities for revision. Involving the same actors throughout the process (from strategic goal setting, to operational development, and to implementation/evaluation) is called vertical integration. Claudia Pahl-Wost says that the essential elements for supporting transformative change are “(1) the link between largely informal learning cycles and formal policy processes; and (2) the vertical coordination of governance levels to capture the role of different kinds of activities at various levels with bottom-up and top-down processes.”

The TCGP is designed to function in cycles, with actors like the Governing Councils moving from the bottom up, and actors like the National Partners moving from the top-down. Over time, through cycles of engagement, it is expected that novel strategies for optimizing grant outcomes will emerge. The design of the TCGP incorporates ideas of polycentric decision making and adaptive governance. Polycentricity can be defined as “a structural attribute of social systems possessing numerous decision centers”. Adaptive governance can be understood as a problem solving process in which solutions are “tested and revised in a dynamic, ongoing, self-organized process of learning by doing.” (Munaretto, 73) Again, we recognize an emphasis in decentralizing power coupled with group learning opportunities.

Embracing a spirit of inclusive polycentricity demands slowing the decision-making process down to allow for deep engagement with stakeholders and adding periods for review, comment, and the revision of goals. “For nonprofit managers, collaborative governance comes with a higher program price tag.” (Johansen, 357) But if the network can build a dynamic polycentric system, the TCGP will have enhanced adaptation, innovation, trustworthiness, and sustainable outcomes.

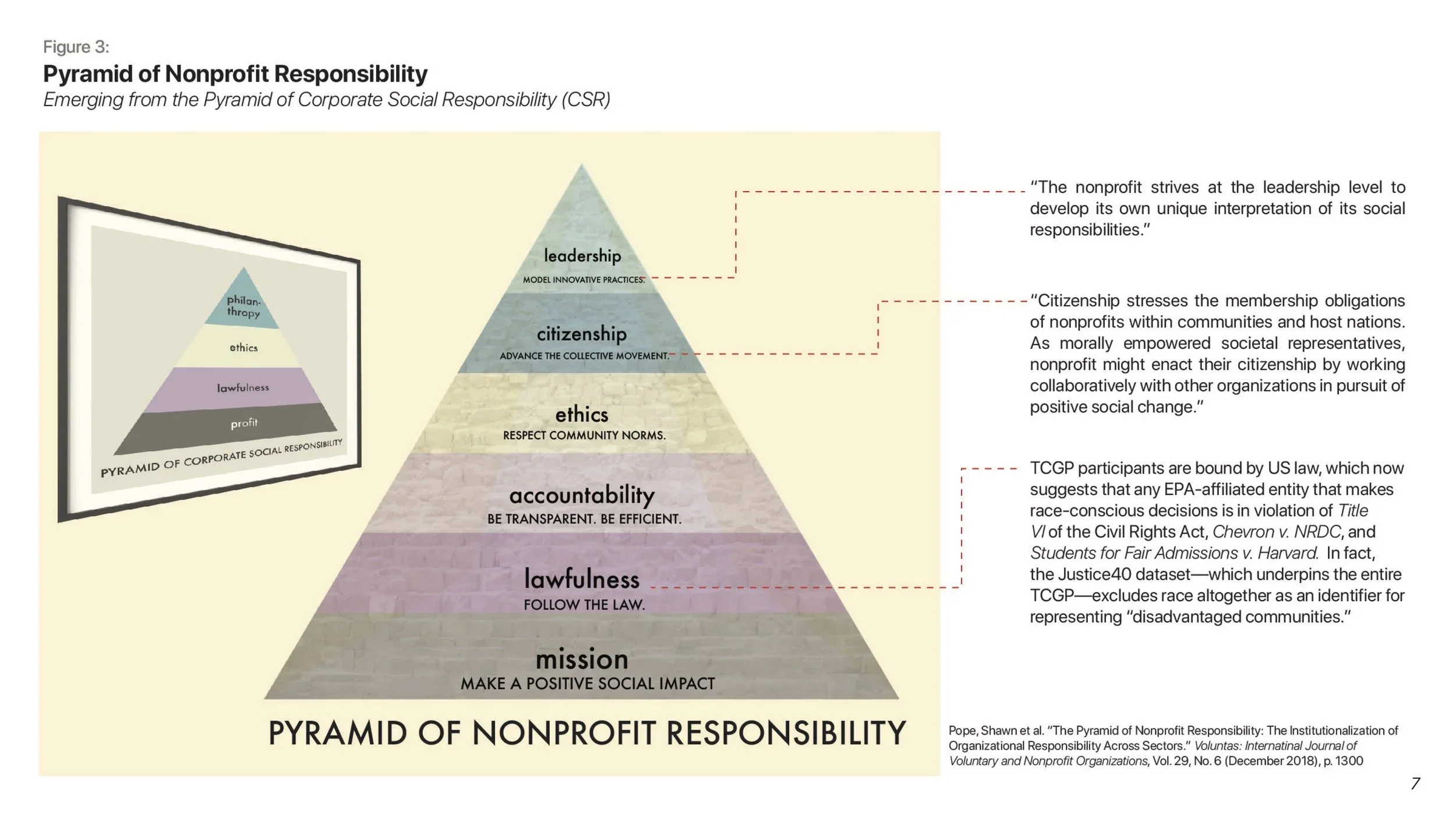

Fig 4.

Based on the Pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Shawn Pope proposes the Pyramid of Nonprofit Responsibility, a framework based centrally on an organization’s mission but also stressing lawfulness, accountability, ethics, citizenship, and leadership.

3. Citizenship

Citizenship is about the advancement of the collective movement: “nonprofits might enact their citizenship by working collaboratively with other organizations in pursuit of positive social change.” (Pope, 1300) The TCGP is an experiment in taking a collaborative coproduction approach to enacting this change, and it hinges on the actors sharing a commitment and passion toward improving ecological resilience and community trust in disadvantaged communities.

A community approach to coordinating the TCGP means moving away from bureaucracies and markets and instead connecting a vast network of clans that provide personalized services and commune with an ever-expanding group of neighbors and CBOs. This is to say that clan-based decision making is great provided that the clan keeps getting bigger! A spirit of citizenship for the National Partners demands an emphasis on recruitment. As the program expands, how can we connect new communities and new CBOs into the TCGP network? This could mean the recruitment of new grant applicants from neglected geographies, but it could also be the inclusion of a young activist into a partnership as workforce development.

Citizenship requires standardized values, norms, and best practices, and outreach duties fall onto the National Partners for consolidating and communicating these shared objectives. Mostly, these values should fall within the parameters of service change, “such as increasing client access to services or providing more holistic treatment.” But the TCGP as a complex collaborative coproduction is also focused on system change, “such as working to alter the existing structure, create new linkages, and decrease service fragmentation.” (Herranz, 312) If successful, program participants’ efforts to work inside the system may collectively emerge into outcomes that potential transform the system itself.

If there is an incident in which someone is excluded from the TCGP due to the enforcement against race-based decision making then the National Partners could connect that individual to legal support for challenging that rejection. The larger fight for environmental justice means getting the right plaintiffs in courtrooms. Likewise, a fight against unjust US law could be galvanized through storytelling and public relations efforts; the National Partners East is well positioned to take the offensive with messaging surrounding legal controversies like the disparate impact standard. We might have to follow the law, but we don’t have to advocate for it.

In discourses surrounding public policy and administration, networked management models such as that demonstrated by the TCGP have unique traits. “High-performing enterprise networks are characterized by managerial roles that include: mobilizing executive leadership, promoting networks, brokering collaborative intervention, developing collaborative capacity, making strategic investments, providing new forms of technical assistance, accessing public value, and providing automatic feedback and learning.” (Herranz, 323) Coordinating across different organizational cultures and missions is going to require a systems thinking approach, which means the National Partners must strive to understand and shape the structures that underlie complex situations. But as John O’Leary writes, “Cross-boundary missions can lead to dramatic, “10x-level” outcomes.”

Bibliography

—Herranz, Joaquin Jr. “Network Performance and Coordination: A Theoretical Review and Framework.” Public Performance & Management Review, March 2010, Vol. 33, No. 3 (March 2010.)

—Johansen, Morgen and LeRoux, Kelly. “Managerial Networking in Nonprofit Organizations: The Impact of Networking on Organizational and Advocacy Effectiveness.” Public Administration Review, March/April 2013, Vol. 73, No. 2 (March/April 2013.)

—Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2013). Embracing Emergence: How Collective Impact Addresses Complexity. Stanford Social Innovation Review. https://doi.org/10.48558/ZJY9-4D87

—Munaretto, Stefania et al. “Integrating adaptive governance and participatory multicriteria methods: a framework for climate adaptation governance.” Ecology and Society. June 2014, Vol. 19. No. 2 (June 2014.)

—O’Leary, John et al. “Crossing boundaries to transform mission effectiveness.” Deloitte Center for Government Insights. (25 March, 2024.)

—Pahl-Wostl, Claudia et al. “How Multilevel Societal Learning Processes Facilitate Transformative Change: A Comparative Case Study Analysis on Flood Management.” Ecology and Society, Dec 2013, Vol. 18, No. 4 (Dec 2013.)

—Pope, Shawn et al. “The Pyramid of Nonprofit Responsibility: The Institutionalization of Organizational Responsibility Across Sectors.” Voluntas: Internatinal Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, Vol. 29, No. 6 (December 2018.)