THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF BALI PROVINCE:

UNESCO and Strategies of Resilience

by Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (17.6 MB)

© 2020 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

Abstract

This report traces the decade-long process through which the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province achieved UNESCO World Heritage inscription, arguing that the case demonstrates UNESCO’s shift toward socio-ecological frameworks rooted in ecological resilience. It outlines the evolution of the “cultural landscape” concept within international heritage governance and examines how the Balinese subak irrigation system—interpreted through J. Stephen Lansing’s social-ecological systems (SES) research—became the organizing logic for both the nomination and the province-wide management plan. While Lansing’s simulation models effectively illuminate the adaptive, collective dynamics of subak networks at small scales, the report critiques the extension of SES and resilience theory to international governance, where scientific language can obscure power imbalances and replicate neocolonial structures. Ultimately, the Bali case illustrates both the promise and limits of ecological resilience as a universal framework for cross-cultural heritage management, raising ethical questions about authority, participation, and the role of global institutions in shaping local landscapes.

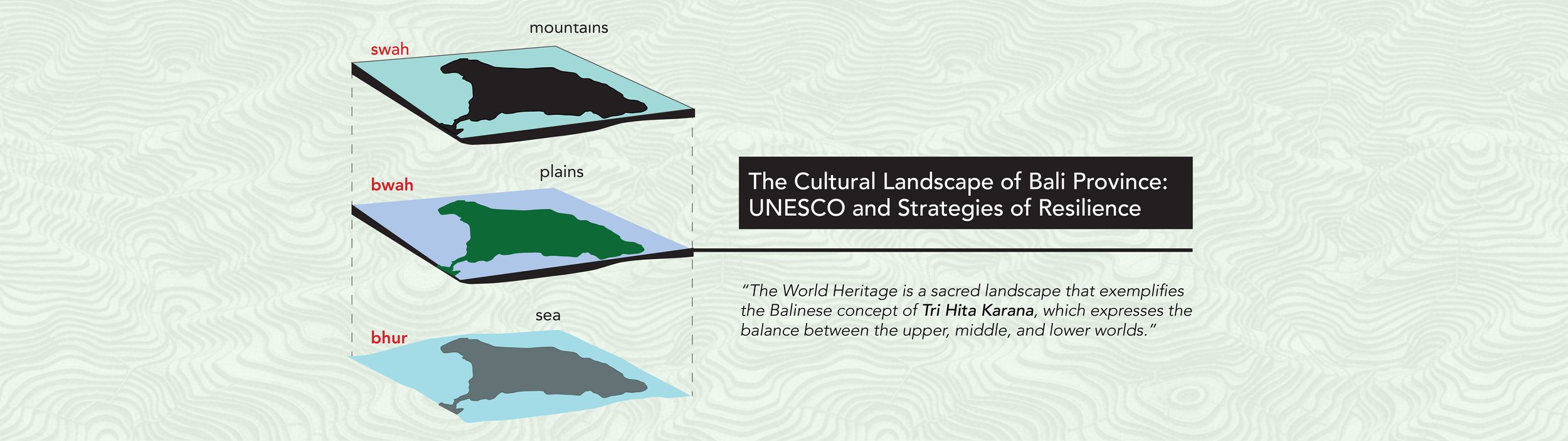

Fig 1.

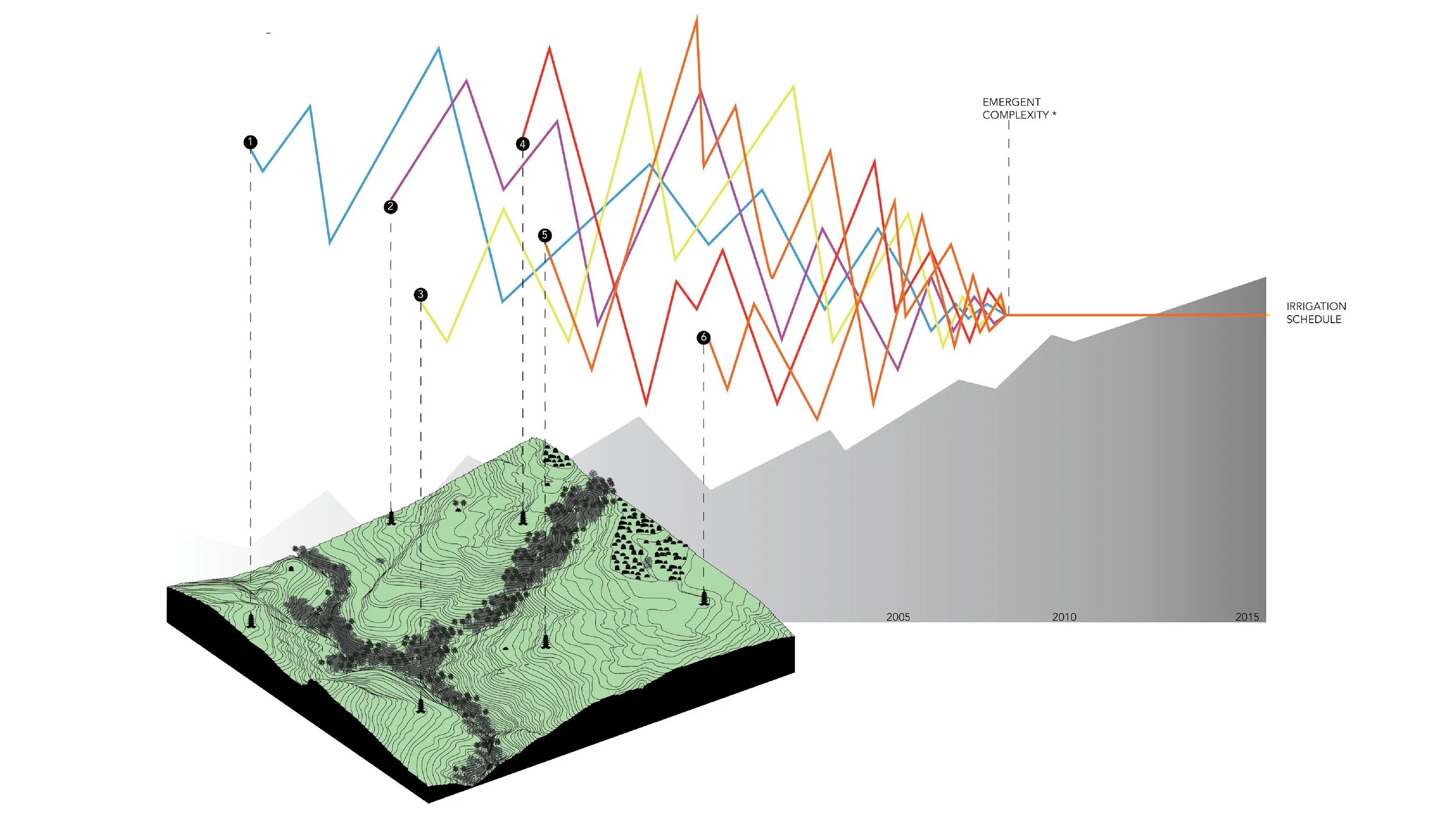

Anchored around Hindi temples and nested within a greater canal system, subaks are institutions of rice farmers that share an irrigation system. This diagram shows that collective management functions ecologically: as subak farmers adapt to a neighbor’s irrigation schedule, optimal harvests and pest management coalesce with emergent complexity. .

INTRODUCTION

This report examines the process by which the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province, or Warisan Budaya Dunia, became inscribed by The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) between its initial application in 2001 to its final inscription as a World Heritage Site in June, 2012.

Today, the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province serves as a prototype for a new, socioecological strategy in the protection of landscapes by UNESCO. The ten-year application process and negotiation between Bali and UNESCO reveals how environmental crisis is not merely a catalyst for change but also a political strategy to unify a diverse set of actors and stakeholders (and their disparate agendas) around a common ideologic vision: ecological resilience.

I will begin with a brief history of the term ‘cultural landscape,’ as it evolved within various United Nations bodies, ultimately applying the term to the Cultural Landscape of Bali Province and its rice-paddy subak irrigation and temple system. However, I will leverage this analysis into a conversation about UNESCO as an international political apparatus. In the case of Bali, academic consultants designed an ‘adaptive co-management system’ that represents a revisionof UNESCO’s previous cultural landscape agenda.

CULTURAL LANDSCAPES

From 1948, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has served UNESCO as a nature conservation organization. From 1965, The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) has served UNESCO to protect cultural heritage. Not until the World Heritage Convention in 1972 did UNESCO establish “a profoundly unique international instrument for recognizing and protecting both the cultural and natural heritage of outstanding universal value.”1

“The concept of cultural landscapes,” contends Aurelie Elisa Gfeller, “offers a potent means by which to analyze the process of (re)negotiation of the meaning of heritage on a global scale.” She cites that three sets of actors led the international debate throughout 2 the 1980s: the French government, nature conservation activities in the framework of IUCN, Heritage List as a landscape. In 1992 the establishment of the World Heritage Center by the Director General of UNESCO established that the protection of cultural landscapes was a global priority.

This was a time with much thought devoted to the combined works of nature and man. In 1995’s Uncommon Ground, William Cronon argues that nature is not essential. “Instead,” he writes, “it is a profoundly human construction,” defined in relation—often 4 in opposition—to human civilization. Recognizing the “otherness” of nature allows scholars across a broad spectrum to approach issues of landscape through a sociocultural lens. Anthropologists and social scientists recognize a dialectical relationship between human society and nature; both are counterparts at work in shaping the landscape. Many cultural and environmental historians connect issues of landscape to issues of social justice, stressing that “those who claim to speak for…the landscape…simultaneously make a powerful claim to power.”5

Indeed these historical issues of power muddled the cultural landscape discussion throughout the 1990s. During an era of unprecedented globalization, issues related to Western economic and cultural imperialism became critical topics of conversation, revealing an inherent contradiction in UNESCO’s criteria for cultural landscapes. At once, the cultural landscape site must demonstrate “a harmonious balance between nature and human activity,” but also the site must represent vulnerability “under the impact of irreversible change,”6 thus warranting international intervention. How can UNESCO both protect an existing land-use pattern (i.e. reinforce local tradition and authority) while simultaneously instituting new management guidelines? Criteria that was based on the nomination of the U.K. Lake District site did not necessarily translate to Eastern sites with colonial histories. How could a Western-led international body interject upon a cultural landscape without thwarting cultural authority?

Today such questions are certainly asked less frequently. Perhaps historians now acknowledge the impossibility of isolationism. Perhaps the emergence and influence of global cities overshadows the more traditional West-East relationship, facilitating a saturation point of cultural assimilation. Some argue that global climate change has permitted a shifting of the international discussion: that the urgency of climate change has incentivized a diverse set ofactors to engage in discussions about sustainability. In “How Climate Change Might Save the World,” Ulrich Beck writes, “Climate change produces a basic sense of ethical violation that creates new norms, laws, markets, technologies, understandings of the nation and the state, urban forms, and international cooperations.” For Beck this transformation 7 exists outside any specific regional debate. Rather, Beck recognizes that the mere perceived ‘existential violation’ of climate change represents a tipping point, an opportunity to galvanize collective action among actors with diverse political wills.

The Cultural Landscape in Bali Province suggests that UNESCO’s current agenda surrounding cultural landscapes is anchored in strategies of ecological resilience. Cultural landscapes are perceived as ‘social-ecological systems’ (SESs), where both human and natural systems exist in an interlocked network of adjustable socio-ecological variables. It is no longer an agenda of preservation, but of curation, management, and design.

In the case of Bali, academic consultants performed this managerial role, namely J. Stephen Lansing of The University of Arizona’s School of Anthropology and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. I am particularly interested in Mr. Lansing’s use of the SES model in his design of an ‘adaptive co-management system’ for the Balinese Governing Assembly, the final step in Bali’s ten-year process of earning UNESCO World Heritage status. To understand the implications of Lansing’s design, I must begin with a brief history of the Balinese subak system and the SES lens through which Lansing first studied subaks in the 1980s.

THE BALINESE SUBAK AS SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL SYSTEM (SES)

One thousand years ago, rice farmers developed small-scale irrigation systems on Bali’s steep volcanic slopes. As these irrigation canals became networked, famers from multiple villages combined to form institutions that coordinated the distribution of irrigation water from a common source, such as a spring or irrigation canal. These developed into subak systems: organized around a hierarchal network of temples, nested within the greater irrigation system, and extending to the Temple of the Crater Lake whose goddess “makes the river flow.”8 irrigation system, and extending to the Temple of the Crater Lake whose goddess “makes the river flow.”8

The intricate, facetted-shaped rice paddies that comprise interconnected subaks are created and maintained over centuries with the labor of hundreds of thousands of individuals. Each subak network manages irrigation schedules, synchronizes crop planting with neighboring subaks, and manages the flooding of paddy fields to deprive pests of habitat. In turn, subak networks manage pest control at the watershed scale.9

Starting in the 1970s, the introduction of western agricultural techniques in Bali revolutionized subak management. Described as the Green Revolution, chemical fertilizers and pesticides were introduced, and the propagation of new rice varieties began to dismantle the traditional subak management system. The benefits proved short-term. Pests developed resistances to chemicals, watershed ecology became grossly polluted, and when the river reached the sea, algae blooms were killing coral reefs.

In the 1980s, Stephen Lansing set out to prove that traditional subak management techniques led to a greater crop yield. “We can grow a water temple network in the computer very easily,” he states. Lansing generated digital simulation models 10 of 172 neighboring subaks. Beginning with a randomized irrigation schedule and assuming that a given subak’s irrigation strategy adapts in accordance to its neighbor’s crop yield, then over ten years, computer simulations show levels of rice yield and pest management that exceeded the current levels attained with Western faming techniques. Additionally, by interlocking human and natural variables into a single simulation, Lansing was able to measure and predict social collective organization among farmers. In fact, within ten years, the models functioned to replicate traditional subak management almost identically to the development of subak practices in real life. This scientific integration of cultural behavior and ecosystem function marks a new approach to the study of cultural landscapes; Lansing offers data-driven proof that community organization performs as a variable within an interlocked social-ecological system(SES).

Based on the data from these non-linear models, Lansing suggests his theory of “emergent complexity:” that the subak water temple system—initially perceived by Westerners as a religious system—performs ecologically, encompassing lakes, forests, rivers, and rice terraces. Approaching traditional subak management strategies 11 within an SES framework allows cultural forces that foster adaptability, diversity, and redundancy to insulate the SES with ecological resilience. Potentially this ecological resilience is even measurable. Responding to Lansing’s simulation models, MacRae and Arthawiguna write:

Subaks are best understood neither as agents nor as subjects, but as parts of larger systems which in turn can be understood not in terms of any policies of practices of “management”, but as “complex adaptive systems”, self-correcting systems integrating hydraulic, ecological, and sociocultural elements.12

The impact of Lansing’s research on UNESCO’s protection of the Bali Province Cultural Landscape is twofold. First, with the ever-evolving definition of ‘cultural landscape,’ Lansing’s models suggest that the regimes of culture and nature are truly, finally one. Second, twenty years later, Lansing’s subak SES models would function as the framework for a sweeping management design of Bali’s World Heritage.

Fig 2.

Stephen Lansing’s models integrate social and ecological variables within a system, simulating collective organization in response to neighboring feedback.

UNESCO & TRI HITA KARANA

In 2001 the Cultural Office of Bali formed a nominating committee called the Technical Working Group, which identified two sites—one based on cultural heritage and one based on natural heritage—for a single nomination to UNESCO’s World Heritage list. In response, a special mission from the UNESCO World Heritage Centre visited the proposed sites and recommended that the committee “cluster the sites as a coherent ‘cultural landscape.’” Further, the mission requested that the nomination dossier include a “common theme of Bali’s cultural landscape as a representation of Balinese-Hindu cosmology.”13

Between 2002-2007 The Technical Working Group sent four additional nomination dossiers to UNESCO that were returned with suggestions from various UNESCO advisory boards. ICOMOS deferred the nomination with the concern that the sites did not reflect “the extent and scope of the subak system of water management and the profound effect it had on the cultural landscape.” Additionally, ICOMOS recommended “the augmentation of traditional management systems to integrate national and provincial support for agro-ecological conservation and local welfare.” Essentially, UNESCO required that 14 the subak cultural landscape be defined by its global value, and that the management plan be defined by its global feasibility.

This five year negotiation period permitted The World Heritage Centre to cultivate The Technical Working Group into a properly-funded international organization operating at UNESCO standards. First, the World Heritage Centre required the committee to adjust its articulation of heritage based on UNESCO criteria. Additionally, UNESCO’s agenda demanded that the Technical Working Group design a comprehensive management strategy that operated on a scale larger than the subak landscape itself. The management strategy needed to perform nationally, incorporating the Indonesian government, and it needed to perform internationally, incorporating UNESCO . The Technical Working Group required an external consultant, an interlocutor who could galvanize diverse stakeholders and agendas around a singular mission. In 2007, the committee recruited Steve Lansing, who, with his students, assisted in revising the final drafts of the Cultural Landscape nomination.15

While the Balinese-Hindu concept of Tri Hita Karana appeared in dossier drafts before Lansing’s official enlistment, the concept became the central rubric for Lansing’s new design proposal. Expressing the balance between the upper, middle, and lower worlds in Balinese-Hindu tradition, the use of Tri Hita Karana certainly addressed ICOMOS’s request for a cosmological theme. But more importantly, Lansing was able to translate Tri Hita Karana into an ecological framework expressing the balance between mountains, plains, and sea.

It is crucial to consider that Tri Hita Karana, an intangible Hindu expression, is here translated into resolute, ecological language. Since the concept promotes the balance between mountains, plains, and sea, Tri Hita Karana becomes representative of a high-performing SES. Based on Lansing’s simulation models having demonstrated the ecological performance of collective subak water management strategies, here Lansing expands the SES model from the scale of watershed to that of the larger province of Bali. An ecological framing of Tri Hita Karana could address stakeholder concerns from the farmer on up to the United Nations, functioning as the mission statement for the large-scale design of an international landscape management coalition.

RESILIENCY & ADAPTIVE CO-MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

The 1973 work of May and Holling observed that ecological systems confront continual, exogenous change, an idea that sharply challenged the long-held belief in a homeostatic ecosystem model. With the understanding that ecosystems operate in a constant state of flux, ecosystem function cannot be measured in relation to a non-existent state of equilibrium. Instead we must perceive ecosystem function by its capacity for resilience, which Hollis defines as “a measure of the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and disturbance and still maintain the same relationships between population or state variables.”16

Ecosystem resilience emphasizes persistence, adaptive capacity, variability, and unpredictability. We have already seen how Lansing’s simulated models suggest that the subak SES—through collective adaptation—has inherent qualities of ecological resilience built into the traditional management system. Herein, the question for Lansing and his students became how to extend this model of resilient management from the scale of the subak rice paddy (and its corresponding direct landscape managers) to the scale of the international stage (and its national and international policymakers who function as indirect landscape managers).

Once again, Lansing’s answer to the question co-opts social-ecological language: adaptive co-management systems. Gabriella Silfwerbrand of The Stockholm Resilience Centre defines adaptive co-management systems as “a step-wise learning process to develop place specific strategies for managing, monitoring, and evaluating a changing environment.”17 Lansing’s earlier research showed that traditional subak management already functioned in this way: resilience stemmed from a system of interconnected subsystems, all providing responsive but decentralized feedback to one another, all within a larger network of nested subaks. Adjusting the SES model to include national and international policy-makers was simply a matter of scale. It was the same as acknowledging that each subak functioned as an ecosystem at the village scale, but that a larger ecosystem—comprised of all the smaller subaks—functioned at the watershed scale. Crucial for Lansing is that an SES model suggested that a singular adaptive co-management system had the potential to build resiliency across the entire network. If Lansing could engage actors across the entire system, he could connect “individuals and institutions at multiple levels, across autonomous regional authorities.”18

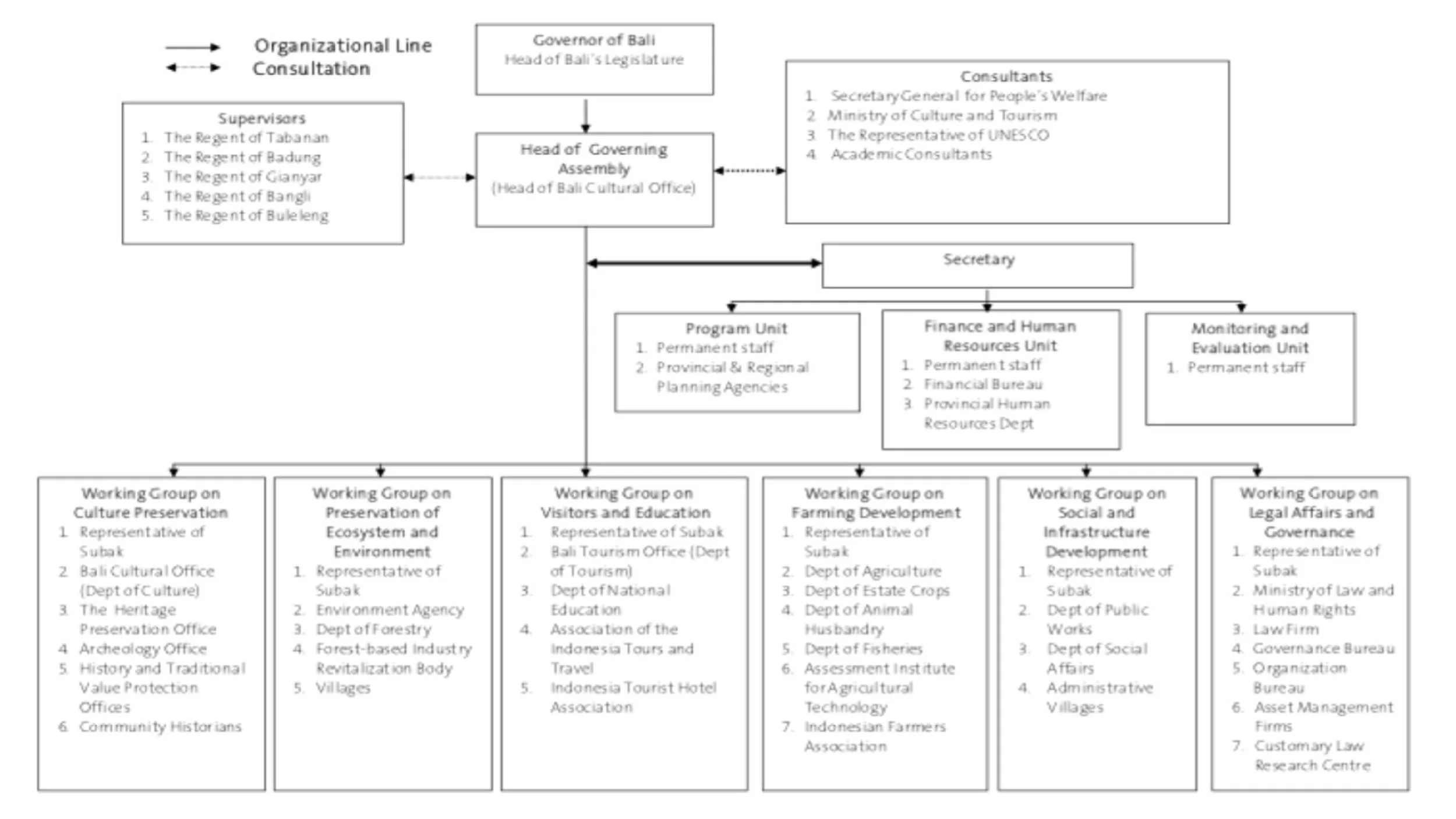

After two years of discussions and an additional deferment from UNESCO, the committee established “a cross-sectoral and multi-level” Governing Assembly for Bali’s Cultural Heritage in March, 2012, based on Lansing’s proposal.19 The plan connected representatives from all stakeholder groups: subak, customary villages, government departments, NGOs, and private sector agencies. (See figure below.)

The establishment of six thematic Working Groups is central to maintaining community authority within the Governing Assembly; subak and village representatives outnumber those from government and non-governmental agencies. This adaptive co-management system leans on the ecological principle that ‘functional redundancy’ and ‘functional diversity’ build ecosystem management resilience.

Karyn Marie Fox, one of Lansing’s students, cites a study by Bahadur et al. in which social-ecological system resilience was examined in order to find major areas of convergence. The findings indicated that “the most significant attribute of resilient systems is diversity of functional groups.” This is echoed by Leslie and McCabe: “Functional redundancy and functional diversity are both generally seen as promoting resilience.” Within 20 the Governing Assembly, each of the six thematic working groups has an independent capacity to adapt to and reform the ever-changing SES conditions, and the rotation of village representation allowed the Working Groups to provide feedback and adapt within an interconnected network.

Fig 3.

The organization of Bali’s Governing Assembly co-opts an SES ecological framework, inserting functional diversity and functional redundancy into multi-scale governance.

ASSESSMENT OF LANSING’S RESILIENCE MODEL

From his early, data-driven work with simulation models to his later duties forming the management structure for the Bali World Heritage Governing Assembly, Stephen Lansing applies a framework of social-ecological systems (SES) upon multiple scales of landscape management design. While I recognize a profound value in Lansing’s longterm stewardship of the subak system, I find significant problems with Lansing’s multi-scalar application of the SES framework, especially as he applies it to governance strategies. In turn, I have concerns with using a model of ‘ecological resilience’ as the singular basis for initiating cross-cultural intervention.

The SES framework functions best for Lansing’s earlier, smaller-scale research. With simulation models, he maps a network of SESs and demonstrates the interconnectivity of human and ecological variables on the scale of a watershed. However, when Lansing scales-up the SES model to provincial, national, and even international scales (via the Governing Assembly), the SES model becomes more of a metaphor and a branding campaign than a scientific framework.

Perhaps even as metaphor or pseudo-science, the SES model might offer valuable managerial insight (promoting adaptation, nesting, and system networking.) But while metaphor begs for interpretation, the language surrounding ecological resilience remains rooted in an epistemologically scientific knowledge system. This scientific vernacular offers Lansing credibility to organize stakeholders around single vision, but it simultaneously burdens Lansing’s proposal with an inflexible absolutism. His scientific authority disenfranchises those whose bottom-up participation might add more to the strength to a long-term management plan.

The insertion of ‘functional diversity’ and ‘functional redundancy’ in the form of community representation in six thematic Working Groups offers a vague sense of adaptive co-management, at best. Do we really assume that functional diversity and redundancy truly lead to management resilience at the international scale? Can the SES design framework perform equally for the rice farmer in Bali as it performs for the diplomat in the Hague?

Resilience theory may not yet be able to answer these questions. In “Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems,” Leslie and McCabe write that “response diversity at one scale may act synergistically with or contrary to the effects of diversity at another scale…the ways in which response diversity at different scales relates to system dynamics within and across scales…bears further investigation…”21

Nevertheless, in approaching the large-scale stage of international landscape management design, I suspect that the role of functional diversity and redundancy in creating SES resiliency might deviate from that expressed in Lansing’s small-scale simulation models. Consider the function of ‘experience’ and ‘memory’ in Lansing’s models: in determining that one neighbor’s rice yield is greater to another, the latter adjusts his management strategy to the former’s. Experience and memory are in fact the variables that interlock human behavior and ecosystem function. Leslie and McCabe’s echo this idea that experience and memory promote SES resilience:

Faced with disturbance of the SES, be it environmental fluctuation or shifting political-economic circumstances, knowledge of how similar conditions were met with in the past, and the outcomes of such actions, can be enormously useful. Experience and memory can thus promote resilience.22

In considering the influence of experience and memory on SES resilience, scale and complexity become essential points of delineation. At the small-scale of Lansing’s simulation models, response diversity takes the form of binary feedback and an associated adaptive strategy. Each actor has two possible responses, and both responses function to increase SES resilience. In turn, experience and memory prove potent variables at the watershed scale.

However, now consider the international-scale of The Governing Assembly’s adaptive co-management SES system. A nebulous collective memory is fueled by complex layers of biased information streams. Feedback networks form disparate, centralized hierarchies. Adaptive responses are nearly impossible to coordinate, and power issues stratify stakeholders and disenfranchise those at that margins. In turn, the larger, more complex scale reveals that experience and memory have a substantially diminished capacity for increasing SES resilience.

One could further argue that following a disturbance, a larger-scaled SES will take a longer amount of time to recover than a smaller one. In Lansing’s small-scale simulation models, it took ten years for collective learning to adjust to a system that reflected traditional subak management. How long might it take for the adaptive co-management system of the Governing Assembly to adapt to is new political relationships?

Indeed the structuring of the Bali Province Governing Assembly amounted to a significant restructuring of political authority from the village to the national scale. Karyn Marie Fox writes, “The Bali process initiated significant change at the national level, creating a parallel structure for cross-sectoral coordination among relevant ministries and departments.”23 As an external consultant aligned directly with neither UNESCO nor Balinese subak farmers, Lansing served as interlocutor, a mechanism to broker this power restructuring. Suddenly, Lansing himself becomes a networked variable, entrenched in a complex and ever-expanding SES. Perhaps it becomes difficult to see the forest for the trees. The SES is too large, and unintended emergent processes begin to dominate the feedback chain.

Indeed Lansing’s work must be analyzed through a colonial framework. In such, one could translate his power brokering as an extension of a domineering power system with roots that extend back to Holland’s initial subjugation of the Balinese people beginning in the 19th century. Historian Stefan Helmreich offers the following critique of Lansing’s work on the Balinese subak system:

“(Lansing) is hardly at the helm of a giant anti-politics machine, ideologically or financially…. His activities might rather be understood as small moments in the production of a dispersed and distributed network of practices that reinstall in more complicated ways some of the patterns of dependency and relations of inequality that have characterized neocolonialism.”24

Helmreich configures Lansing’s ecological resilience model within a legacy of Western dominance of Balinese autonomy. Can Lansing’s co-management adaptive system function to disrupt these ‘patterns of dependency and relations of inequality?’ Or does the SES framework simply replace previous mandates that enacted the subjugation of cultural, economic, and geographic authority?

Such questions are not an attack on resilience theory. Increased ecosystem resilience at all scales is of critical global importance. The problem is that resilience is hard to measure. Even in the analysis of small-scale SESs, long periods of observation result in elusive, conceptual explorations of resilience. Leslie and McCabe suggest that it is problematic to make generalizations about casual relationships within complex systems in the context of historical contingency and path dependency. “Indeed,” they write, “resilience is more properly seen as an emergent property of a complex system than a directly measurable characteristic.”25

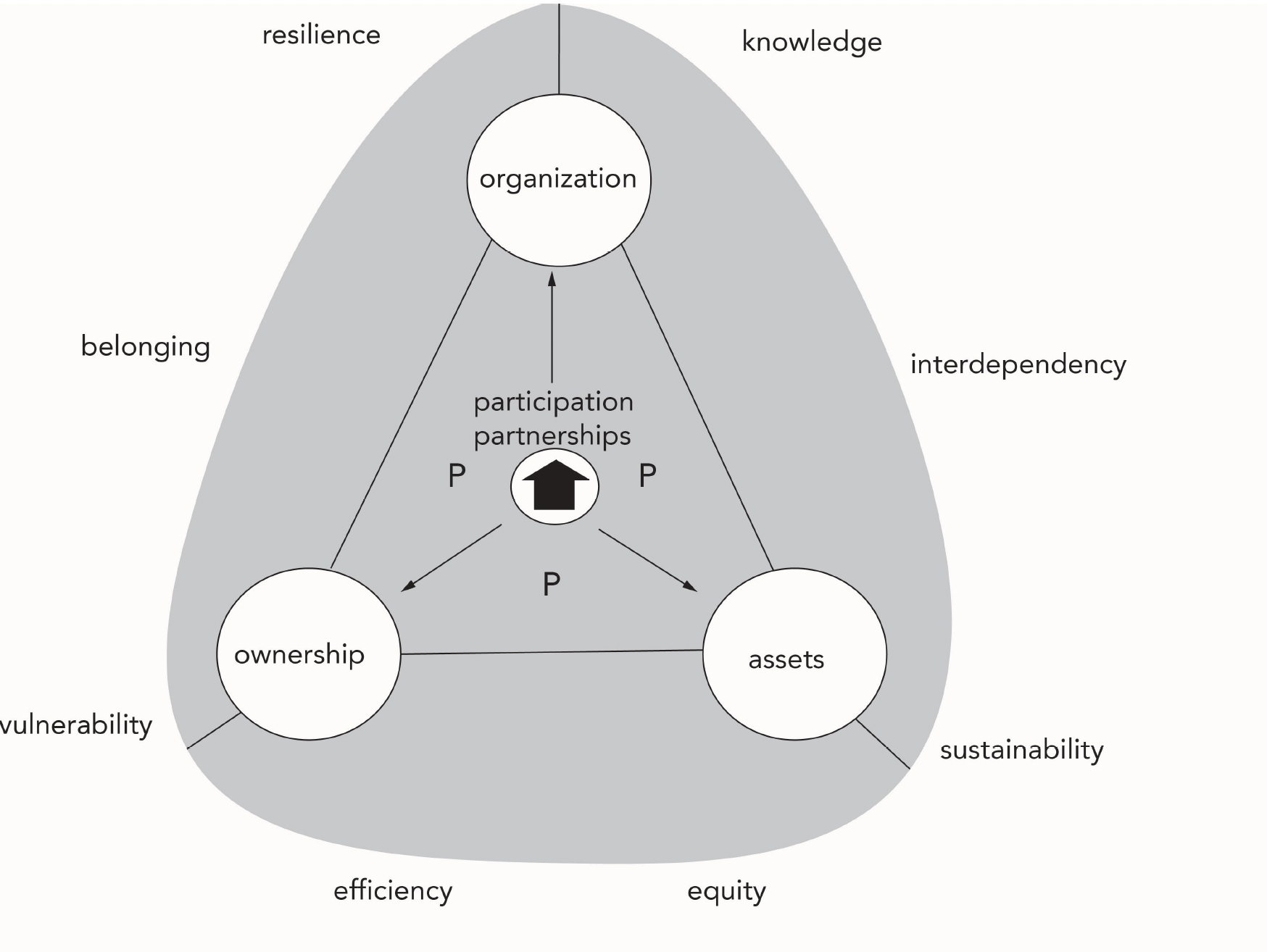

Fig 4.

How do we decide how to decide? A Participatory Design Model by Nabeel Hamdi emphasizes that resilience and sustainability are functions of participation partnerships.

CONCLUSION

I am compelled to acknowledge a wider representation of Lansing’s efforts in Bali. Admittedly I have cherry-picked his simulation models and his structuring of the Governing Assembly to emphasize the pitfalls in monotheistically leaning on an ecological resilience framework. However, Lansing’s project “Using the Design of Bali’s World Heritage Cultural Landscape to Empower Balinese Communities” rests heavily on a participatory design framework. Like resilience theory, participatory design is embedded in the the concept that the world exists in a constantly-changing state of flux. However, participatory design is embedded in the notion that every site is unique, undefinable, and unknowable. Resiliency must be built slowly and indirectly from the bottom up. There is almost an Aristotelean virtue to the participatory design process: the development of practical wisdom, good judgement, and prudence. (See diagram above.)

Lansing’s “Subak Traveling Exhibition and Guidebook Proposal” was designed to implement the strategy laid out by the Governing Assembly. Educational materials related to management strategies travel between subak communities, distributing and collecting feedback. Lansing takes a humbler, softer tone with this project. He is speaking to the Balinese people when he writes that when it comes to governing World Heritage sites, “the failure rate is very high, especially for landscapes where the twin goals of biological and cultural diversity conservation must somehow be reconciled.”26

Lansing’s work on the conservation of the subak has spanned five decades. It is a project from the heart. Questions on the ethics of international development lie close to my own heart as well. For five years I have worked with a cluster of villages in Flores, Indonesia, designing a sustainable water delivery system and a management organization. Performing as an actor in a very small-scaled cultural landscape SES, I have needed to adapt my own stated criteria and methodology for cross-cultural intervention over the years. Memory functions to remind me of the history of subjugation that I represent; experience functions to assure me that history is doomed to repeat itself. Acknowledging the nonexistence of universal absolutes and moralities has anchored my ethical framework for exploring cultural issues.

However, concurrently—and with great contradiction—I also recognize that the acknowledgment of a shared universal morality is the only reasonable ethical framework on which to base cross-cultural intervention. It is a contradiction that pervades all methodologies of international development. How do we decide how to decide? At once, Lansing must acknowledge the unavoidability that his management design reinforces power inequalities, yet simultaneously he must adhere to a mission of empowering vulnerable peoples and landscapes. To circle back to an earlier question: how can UNESCO both protect an existing land-use pattern (i.e. reinforce local tradition and authority) while simultaneously instituting new management guidelines that thwart its political autonomy?

In the case of Bali, issues of ecological sustainability function as the framework to build a shared, universal morality. Cultural issues are neatly packaged within an SES framework, and the international intervention process becomes almost transactional: Bali adjusts local infrastructure and management to UNESCO’s cosmopolitan criteria, and UNESCO will offer the agency for a long-term stewardship program. In turn, perhaps the rest of the globe can draw its own lessons from Bali’s tradition of socio-cultural sustainability.

The ongoing discussion and reevaluation of the term ‘cultural landscape’ represents a collective effort to characterize shared moral values. This year, the United Nations published seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) as part if its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Goal 13.1 is stated as such: “Strengthen resilience and adaptive capacity to climate-related hazards and natural disasters in all countries.” Perhaps if the SES model provides a feasible framework and catalyzes collective momentum, we can excuse its shortcomings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

—1 Roessler, Mechtild. UNESCO and Cultural Landscape Protection. (New York: Gustav Fischer in cooperation with UNESCO, 1995) p. 42.

—2 Gfeller, Aurelie Elisa.“Negotiating the Meaning of Global Heritage: ‘Cultural Landscapes’ in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, 1972-92.” Journal of Global History. Vol. 8 Issue 3: 02 October 2013, p 484

—3 UNESCO Archives, CLT WHC EUR 56, Statement made by P.H. C. Lucas to the expert group on cultural landscapes, Le Petite Pierre, France, 23-26 October 1992.

—4 Cronon, William. Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature. (New York: Norton, 1995) 4

—5 Gfeller, 486

—6 Roessler, Mechtild p. 43

—7 Beck, Ulrich. “How Climate Change Might Save the World: Metamorphosis.” Harvard Design Magazine. p. 90

—8 Fox, Karyn Marie. “resilience In Action: Adaptive Governance For Subak, Rice Terracs, and Water Temples in Bali, Indonesia.” A Dissertation. School of Anthropology, University of Arizona. 2012. p. 46

—9 Fox, p.38

—10 Lansing, Stephen. “Perfect Order - Recognizing Complexity in Bali: John Stephen Lansing at TEDxNTU”, youtube.

—11 Lansing, “Perfect Order”

—12 Arthawiguna, I.W.A. & MacRae, Graeme. (March, 2011) “Sustainable Agricultural Development in Bali: Is the Subak an Obstacle, an Agent or Subject?” Springer Science and Business Media.

—13 Fox, p. 146.

—14 Fox, p.148

—15 Fox, p.149

—16 Leslie, Paul & McCabe, J. Terrence. “Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-Eco logical Systems.” Current Anthropology, Vol. 54, No. 2 (April 2013), p. 115

—17 Silfwerbrand, Gabriella. “Interpretations of a Cultural Landscape: A Case Study In Implementation of Adaptive Co-Management In Bali’s Subak Cultural Landscape.” Masters Thesis. Stockholm Resilience Centre. 2012. p. 58

—18 Fox, 150

—19 Fox, 153

—20 Leslie and McCabe, 115

—21 Leslie & McCabe, 114

—22 Leslie and McCabe, 116

—23 Fox, 158

—24 Lansing, Steve “Foucault and the Water Temples: A Response to Helmreich,” A Critique of Anthropology, Vol. 20 (3). 2000. p. 309

—25 Leslie and McCabe, 116

—26 Watson, Julia Nicole & Lansing, J. Stephen. (2012) “Using the Design of Bali’s World 26 26 Heritage Cultural Landscape To Empower Balinese Communities” Subak Traveling Exhibition and Guidebook Proposal