THE THRIVING COMMUNITIES GRANTMAKING PROGRAM (TCGP) LAID TO REST

Lessons from a Short-Lived Experiment in Environmental Justice Governance

by Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (8.8 MB)

© 2025 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

Abstract

The Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program (TCGP) was launched by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2023 as a centerpiece of the Biden Administration’s Justice40 and environmental justice (EJ) agenda. Its aim was to shift decision-making, funding authority, and technical support closer to frontline communities by routing federal resources through national intermediaries—nonprofit “Grantmaker Partners”—who would administer subgrants, capacity-building, and community engagement support. The program is a landmark in the federal government’s adoption of transformative governance principles—like decentralization, loop learning, and bottom-up decision-making. By dispersing management authority across dozens of participatory co-governance partnerships, the program sought to correct the long-standing exclusion of Black, Brown, Indigenous, and low-income communities from federal benefits and climate adaptation planning.

Despite its promise, the program faced persistent criticisms—including questions about the selection and performance of the nonprofit intermediaries, concerns about transparency in subgrant distribution, and arguments that the model reproduced the very inequities it sought to redress. After congressional scrutiny, internal reviews, and an incoming presidential administration determined to eradicate all environmental justice programming, the EPA shut down the TCGP in early 2025, effectively ending the experiment just as many communities were becoming familiar with the model.

The termination raised difficult questions about the future feasibility of race-conscious or EJ-centered federal policy, and whether it should be implemented by private nonprofits, whose internal dynamics and accountability structures are sometimes misaligned with the legal responsibilities associated with delivering public services. The following report explores the decentralized design of the TCGP, examining the program’s complicated legal context as well as the accountability challenges it faced as a public-nonprofit coproduction.

1. Legal Context of Environmental Justice at the EPA

Environmental justice at the EPA operates within a layered and increasingly constrained legal framework. Executive Orders 12898 (1994) and 14008 (2021) demanded that federal programs account for racial and socioeconomic disparities in environmental harm, even as courts and civil-rights law limited the use of explicit racial classifications. Within this space, the TCGP was built on the premise that federal resources should be directed toward communities facing disproportionate environmental and public-health burdens, disparities that are closely correlated with race and income.

At the same time, the program was shaped by ongoing tension between statutory authority, administrative discretion, and Title VI compliance. The TCGP sought to navigate these constraints by relying on place-based indicators, cumulative impacts, and patterns of historic disinvestment rather than race as a formal criterion. However, this approach also granted significant discretion to intermediary organizations to define priority communities and implement equitable grantmaking practices, a flexibility that later drew scrutiny as oversight shifted toward concerns about neutrality, accountability, and the delegation of federal authority to nonprofit actors.

Fig 1.

The TCGP was designed to directly confront the first three dimensions of justice: distributional justice, procedural justice, and recognition justice. It is the aggregate of these—transformational justice—that becomes fraught. US legal statutes block a race-based or “reparations” approach to resource redistribution. Many nonprofits associated with the TCGP, however, are explicitly committed to race-based outcomes.

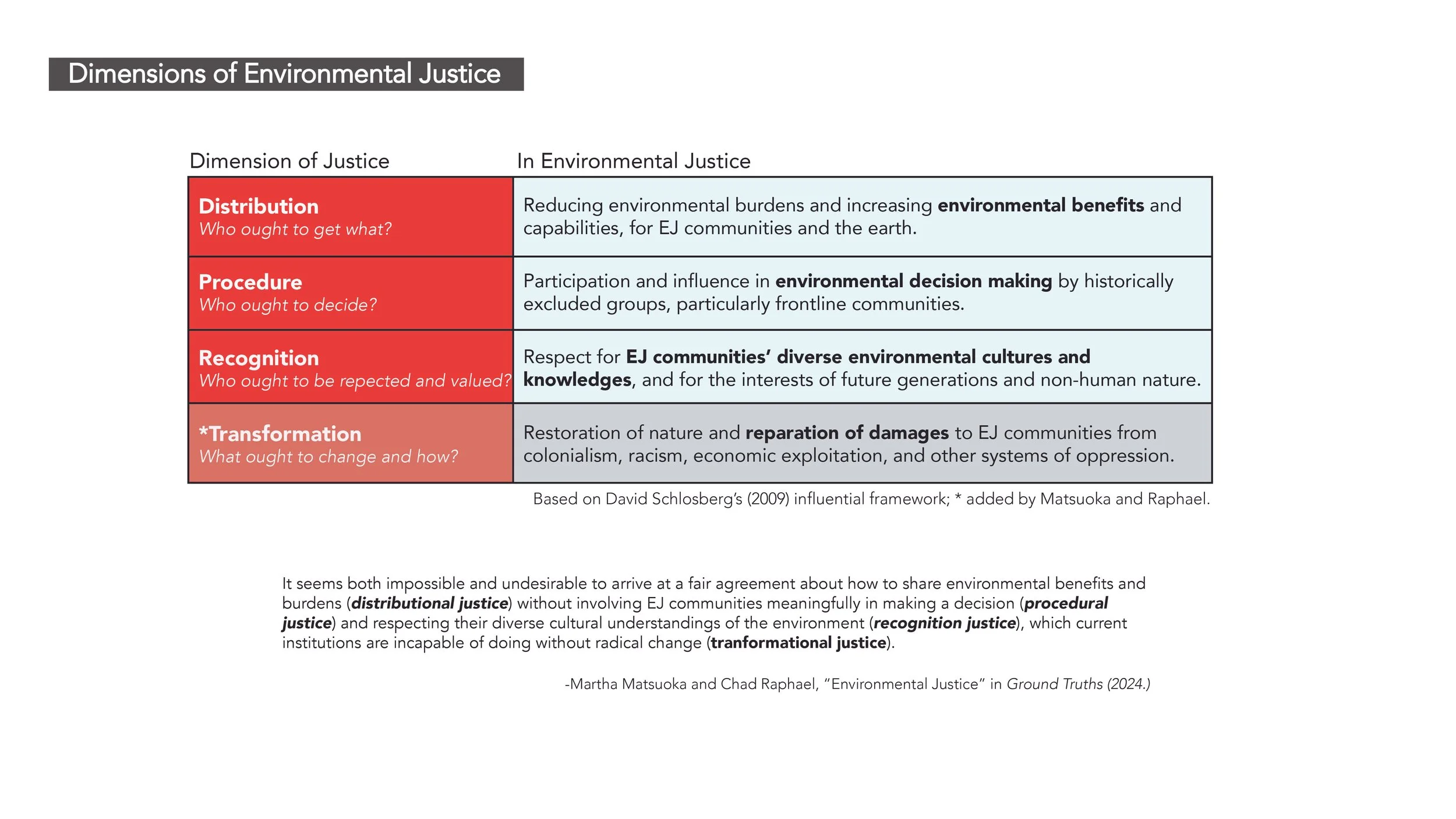

Fig 2.

From the early 1990s, the EPA framed environmental justice as environmental equity, focusing on identifying disproportionate environmental risks faced by low-income and minority communities. By 2023, through Executive Order 14096, the agency’s understanding of environmental justice expanded beyond procedural fairness to include substantive outcomes, explicitly addressing cumulative and climate impacts, systemic barriers, and equitable access to healthy and resilient environments for a broader set of communities.

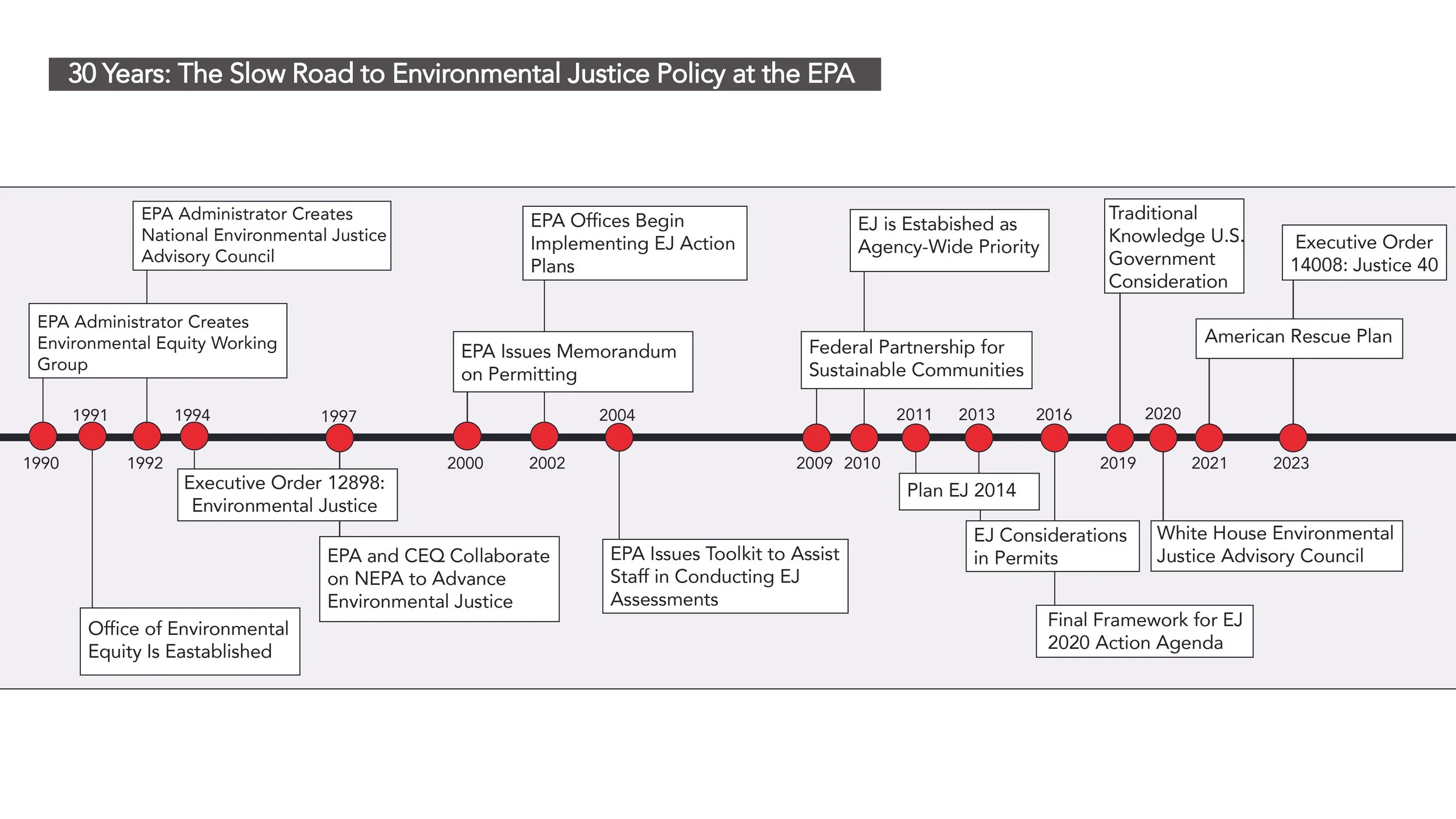

Fig 3.

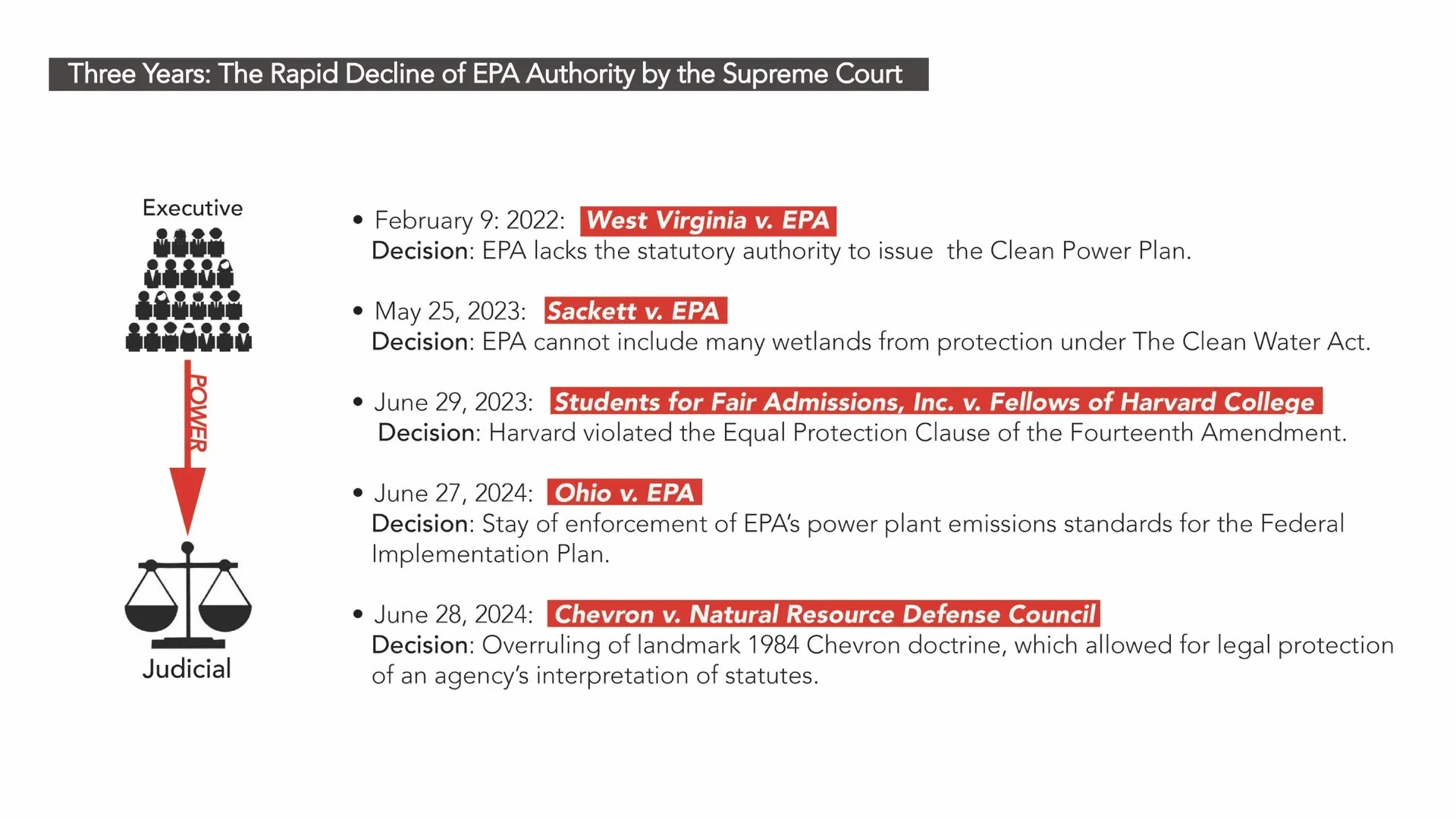

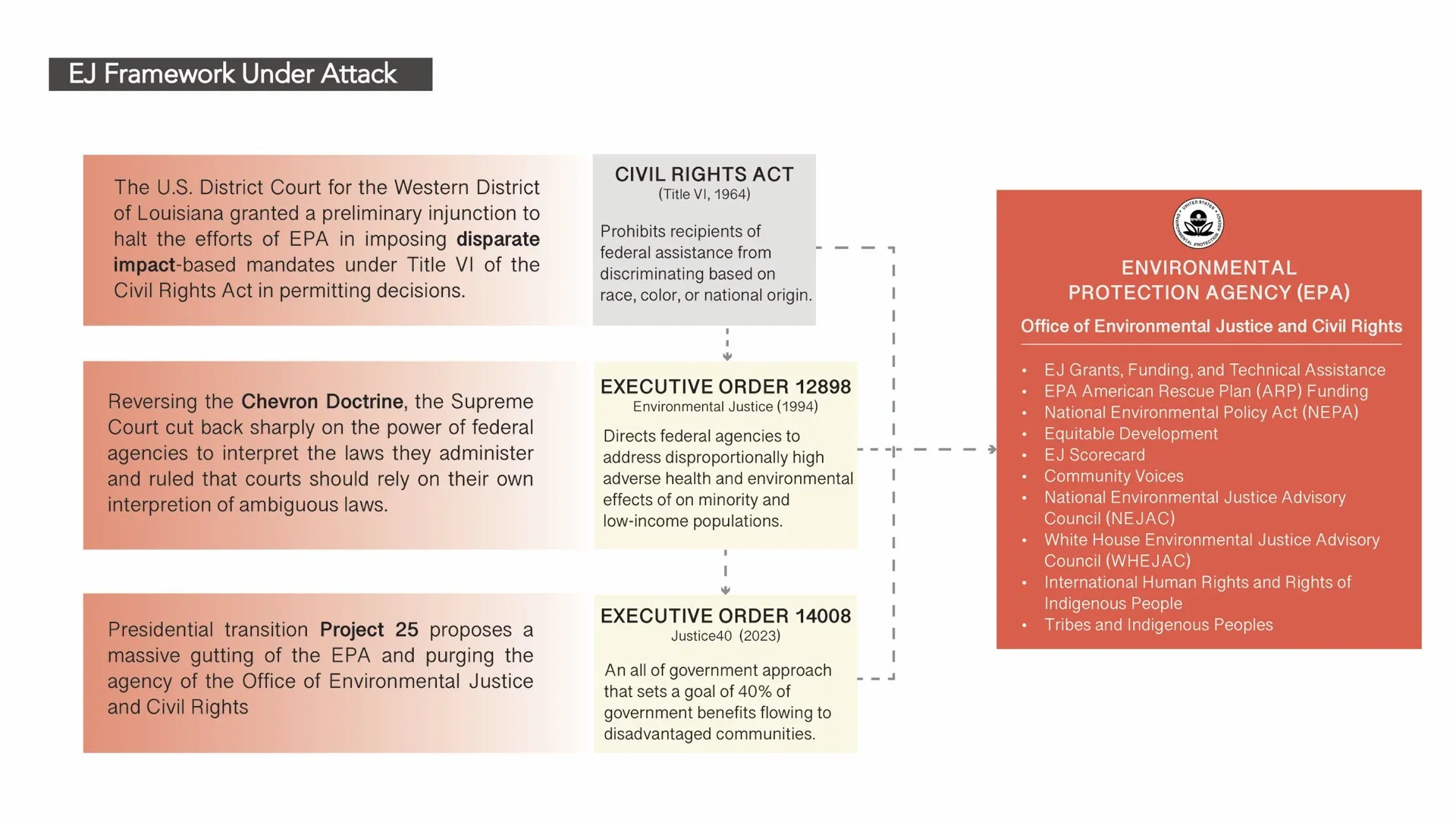

Taken together, these Supreme Court decisions substantially contract EPA authority by shifting power from expert agencies to courts and Congress. Most consequentially, the rejection of Chevron deference caps this trend by stripping EPA of presumptive interpretive authority, meaning future environmental regulation will depend far more on explicit congressional authorization and judicial approval than on agency expertise.

Fig 4.

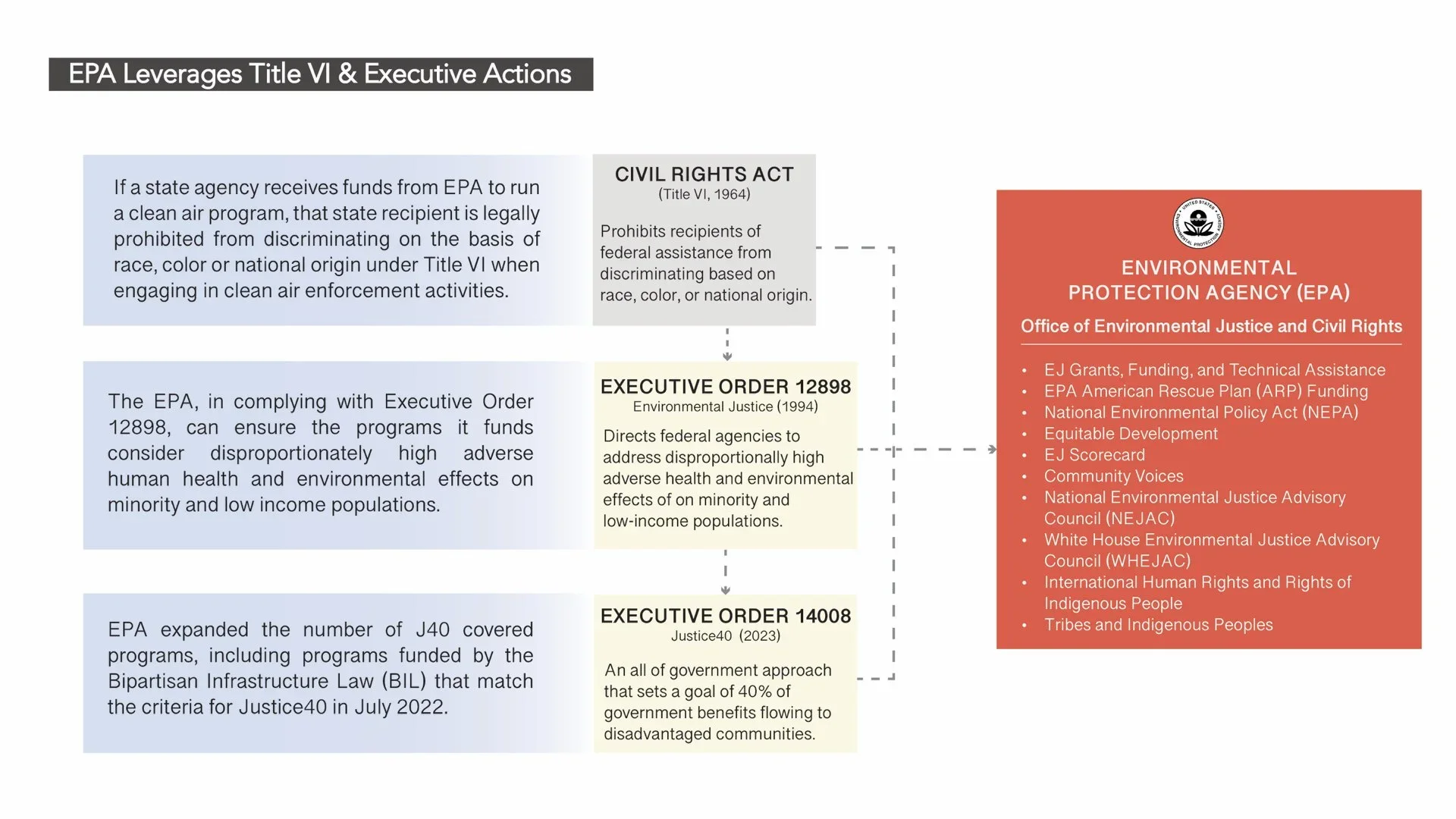

Before 2025, the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and Civil Rights leveraged Title VI of the Civil Rights Act and Executive Orders 12898 and 14008 to focus on projects that identify and reduce disproportionately high environmental and public health burdens in low-income, minority, Tribal, and other overburdened communities, while promoting meaningful public participation in federally funded and permitted actions.

Fig 5.

After 2025, the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and Civil Rights saw its role significantly narrowed rather than formally eliminated, as a result of a combination of judicial, legal, and political constraints. Recent Supreme Court decisions limiting agency discretion, narrowing statutory jurisdiction, and rejecting Chevron deference reduced EPA’s ability to use Title VI and executive-order–based authorities to pursue broad, outcome-oriented environmental justice interventions, especially where Congress had not spoken clearly.

Fig 6.

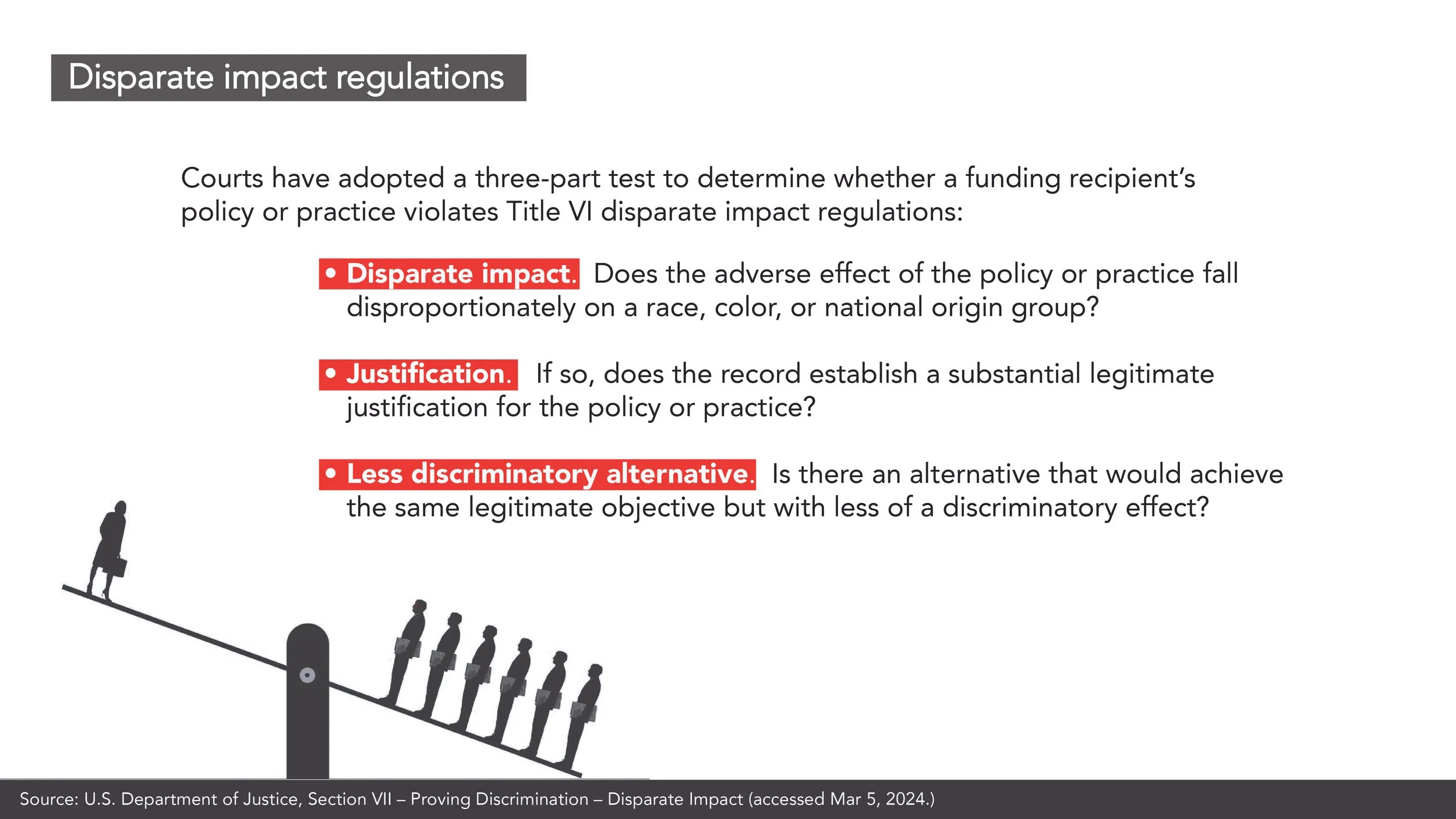

Disparate impact refers to a legal theory under civil rights law in which a policy or practice that is neutral on its face disproportionately harms a protected group, even without intent to discriminate. Legally, it is determined through evidence showing that the challenged action causes a statistically or demonstrably disproportionate adverse effect on a protected class, after which the burden shifts to the decision-maker to show the policy is necessary to achieve a substantial, legitimate objective.

Fig 7.

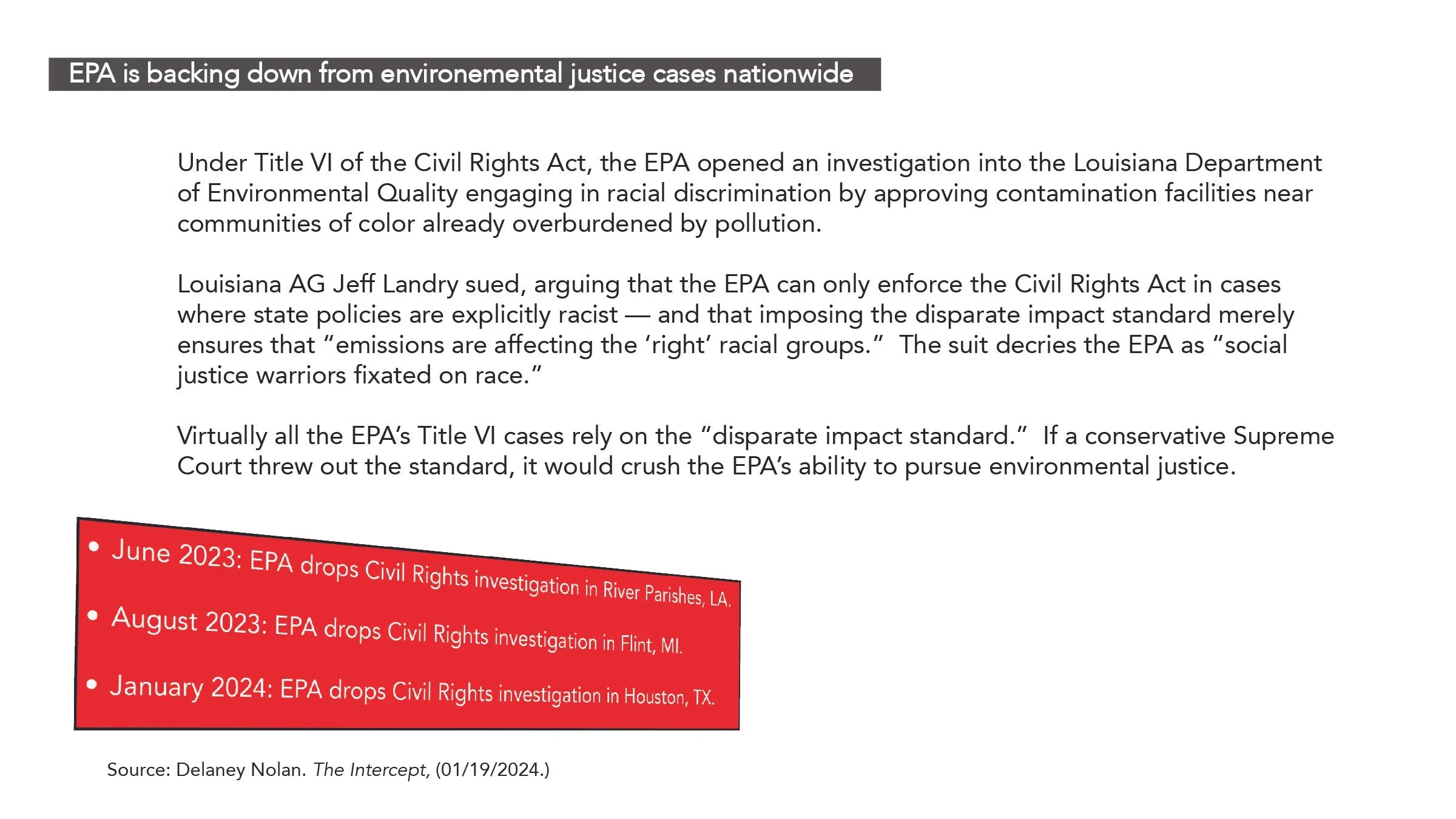

The EPA is no longer bringing proactive environmental justice cases and now limits its role to narrow civil rights compliance reviews of federally funded programs. It avoids claims based on disparate impact or cumulative harm that would require broad statutory interpretation. As a result, most EJ disputes are now pushed to the states or resolved through the courts rather than through EPA enforcement.

Fig 8.

Environmental justice at the EPA is likely to persist, but in a more modest and legally cautious form. Rather than driving policy through expansive interpretations of environmental statutes, the agency will probably anchor EJ work in explicit congressional mandates, data collection, and narrowly framed civil rights compliance. Unless Congress clearly restores or expands EPA authority, EJ will increasingly function as an analytical lens and accountability check, not a standalone enforcement engine.

2. Organizational Structure of the TCGP

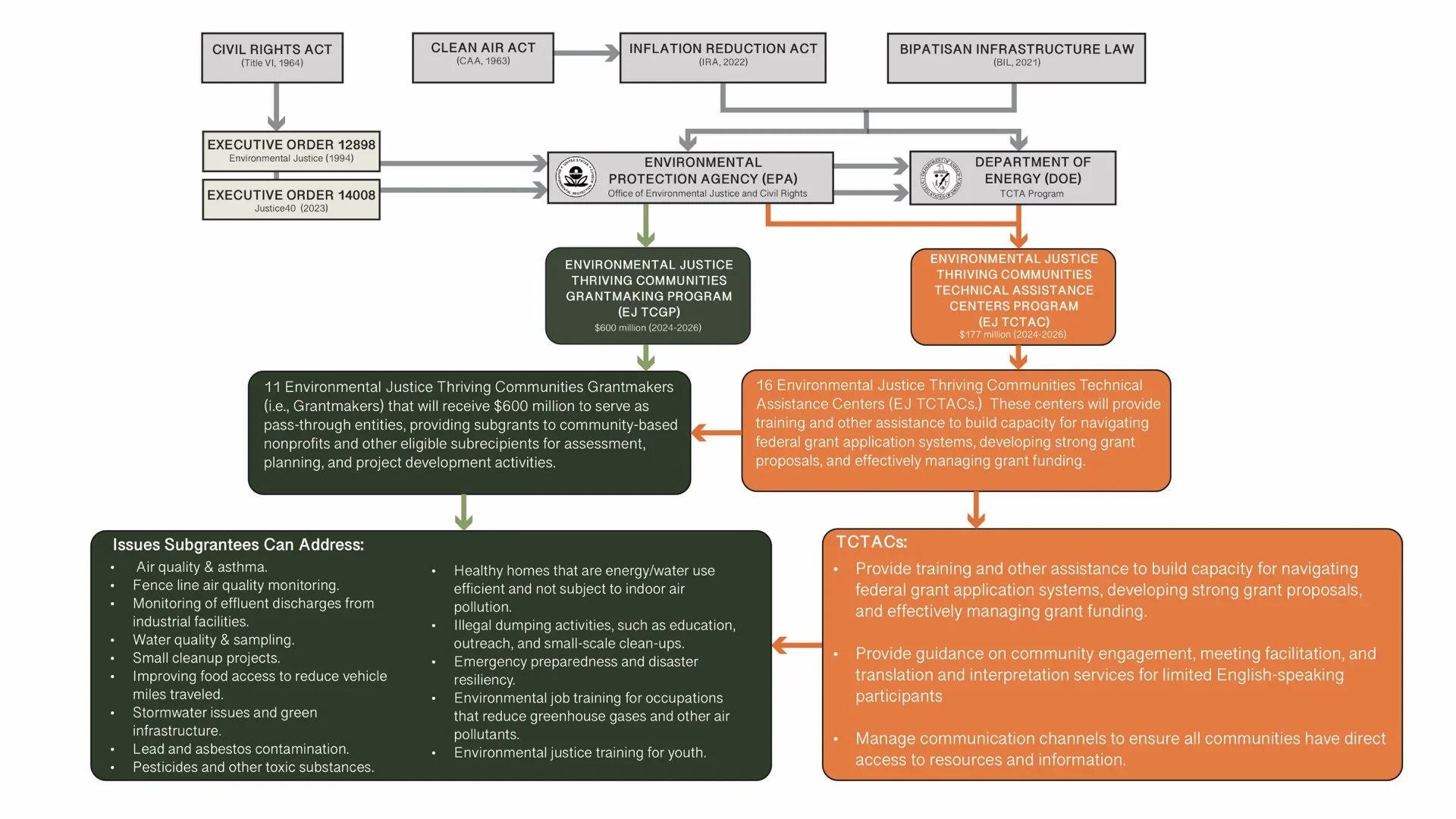

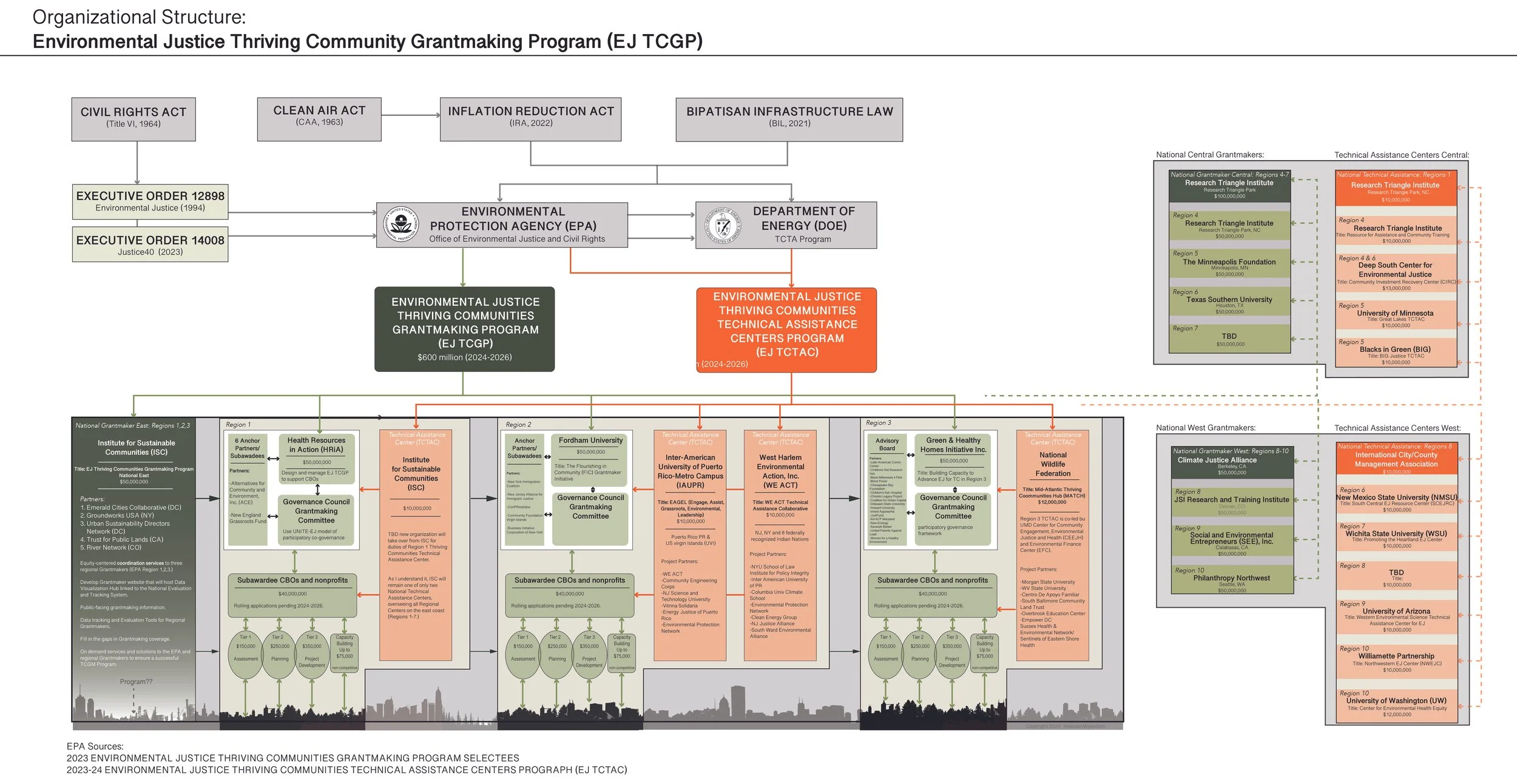

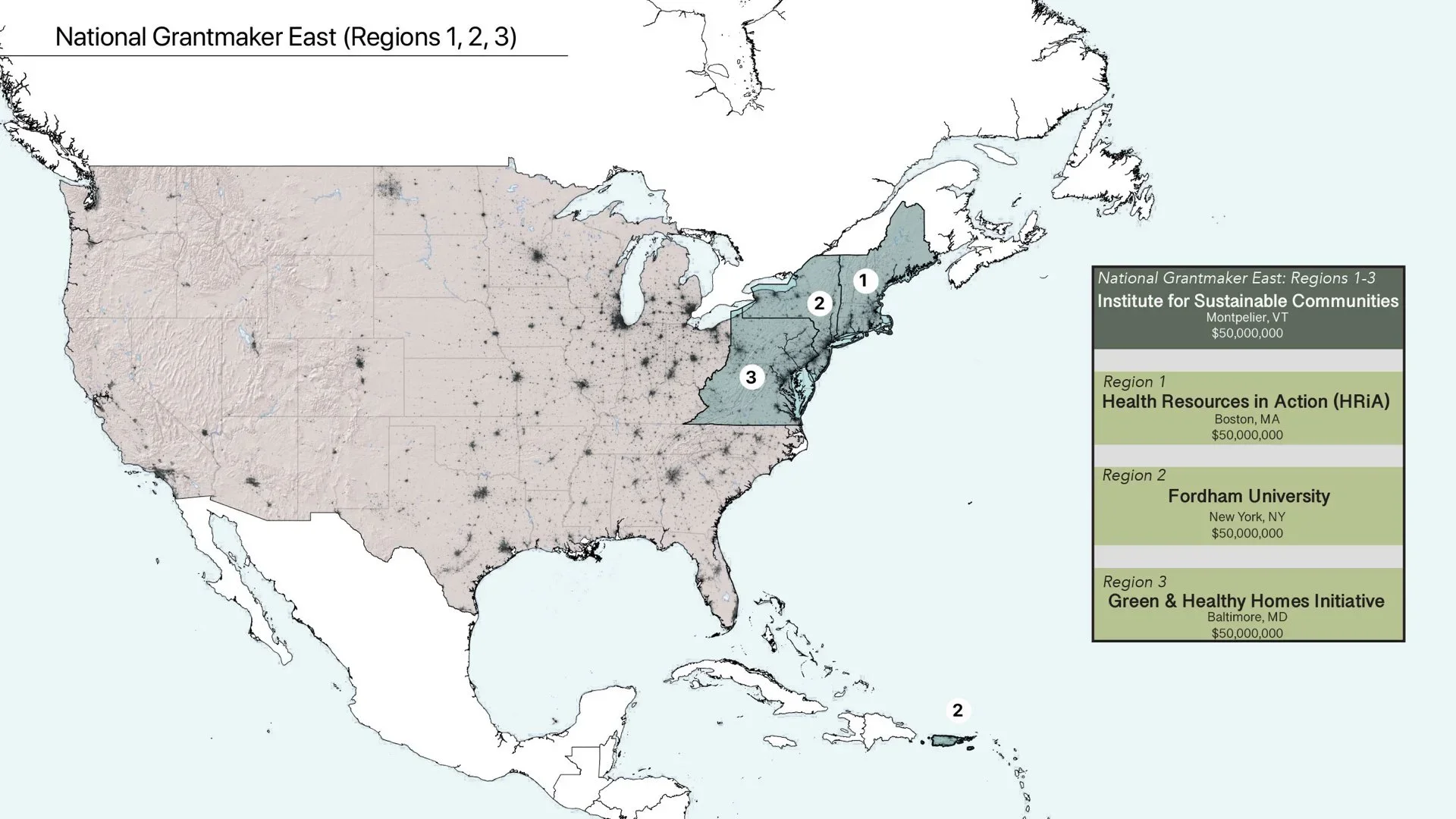

The TCGP’s structure relied on a distributed network of National Grantmaker Partners—large, established nonprofits tasked with regional grant administration, technical support, and capacity-building. Rather than operate a single federal pipeline, the EPA designed the TCGP as a consortium model: the agency provided broad goals and compliance requirements, while intermediaries possessed primary authority over outreach, application review, community engagement, and subgrant awards.

This architecture was intended to embody the EJ principle of bottom-up governance. By working through organizations already embedded in community networks, the EPA aimed to reduce bureaucratic distance and enable more culturally responsive decision-making. However, this structure also magnified the influence of a relatively small set of nonprofit institutions whose prior relationships, professionalized grantmaking norms, and internal governance practices shaped which communities were prioritized. While many intermediaries brought deep EJ commitments, their operational cultures sometimes resembled traditional philanthropic gatekeeping more than participatory co-governance. The resulting tension—between the program’s ideological intention and the practical realities of nonprofit administration—became increasingly evident during audits and congressional inquiries.

Fig 9.

The Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program was shaped far more by executive orders than by explicit congressional statute. Its structure and goals flowed from Executive Orders 12898 and 14008, which directed EPA to advance environmental justice and Justice40 priorities without creating a specific statutory program. As a result, EPA built the TCGP using general grant authority, leaving it vulnerable to legal and political reversal.

Fig 10.

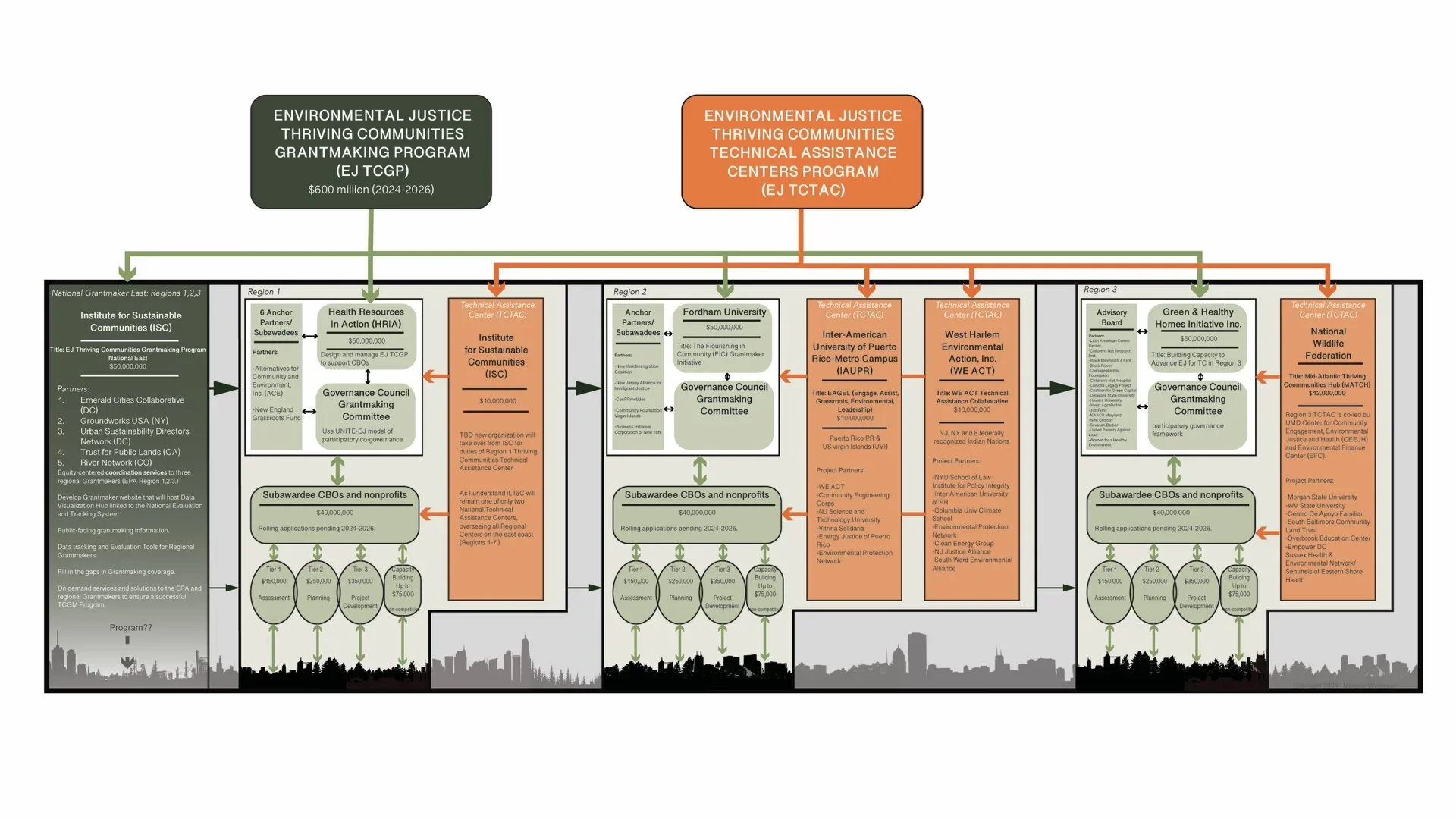

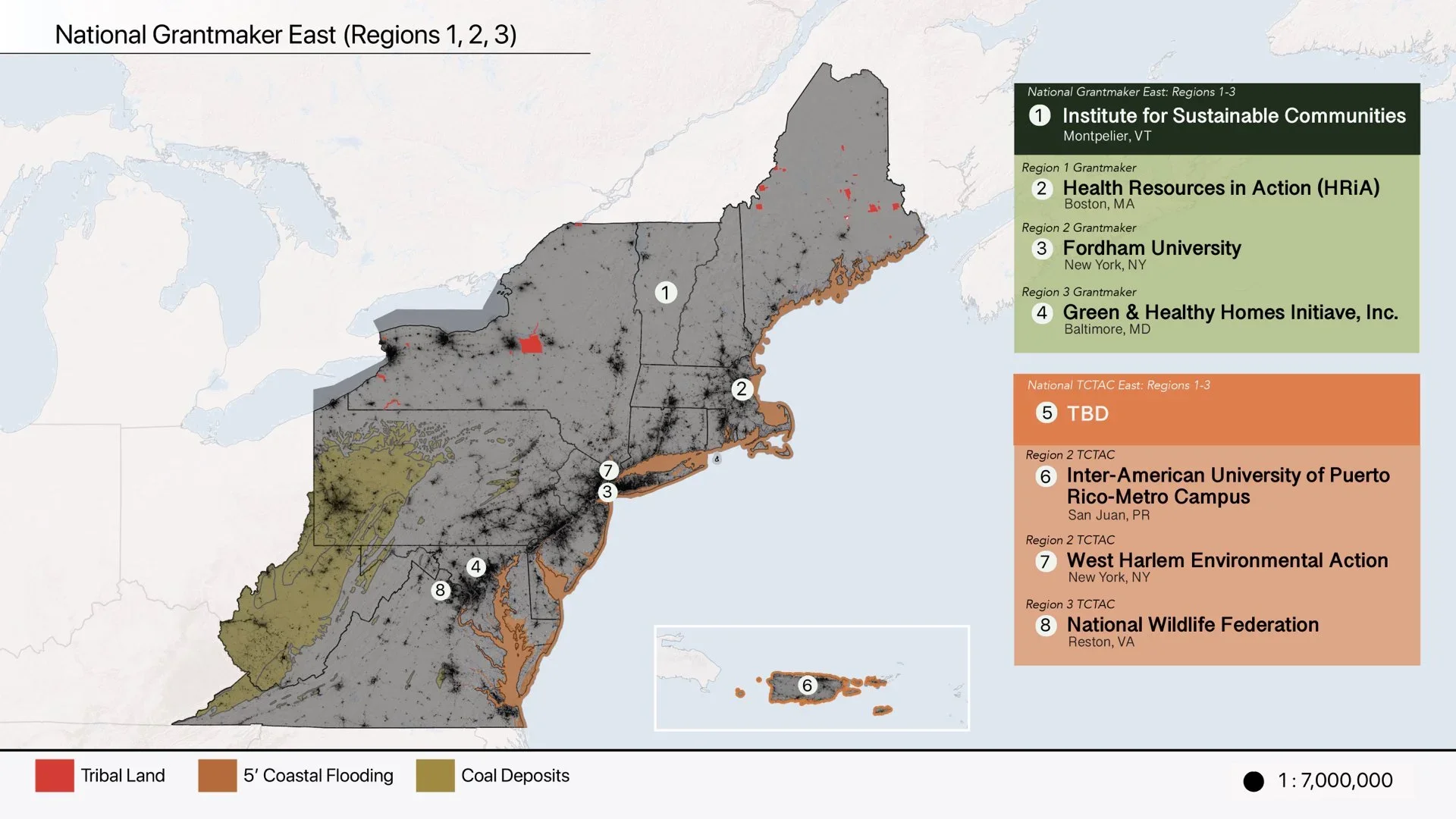

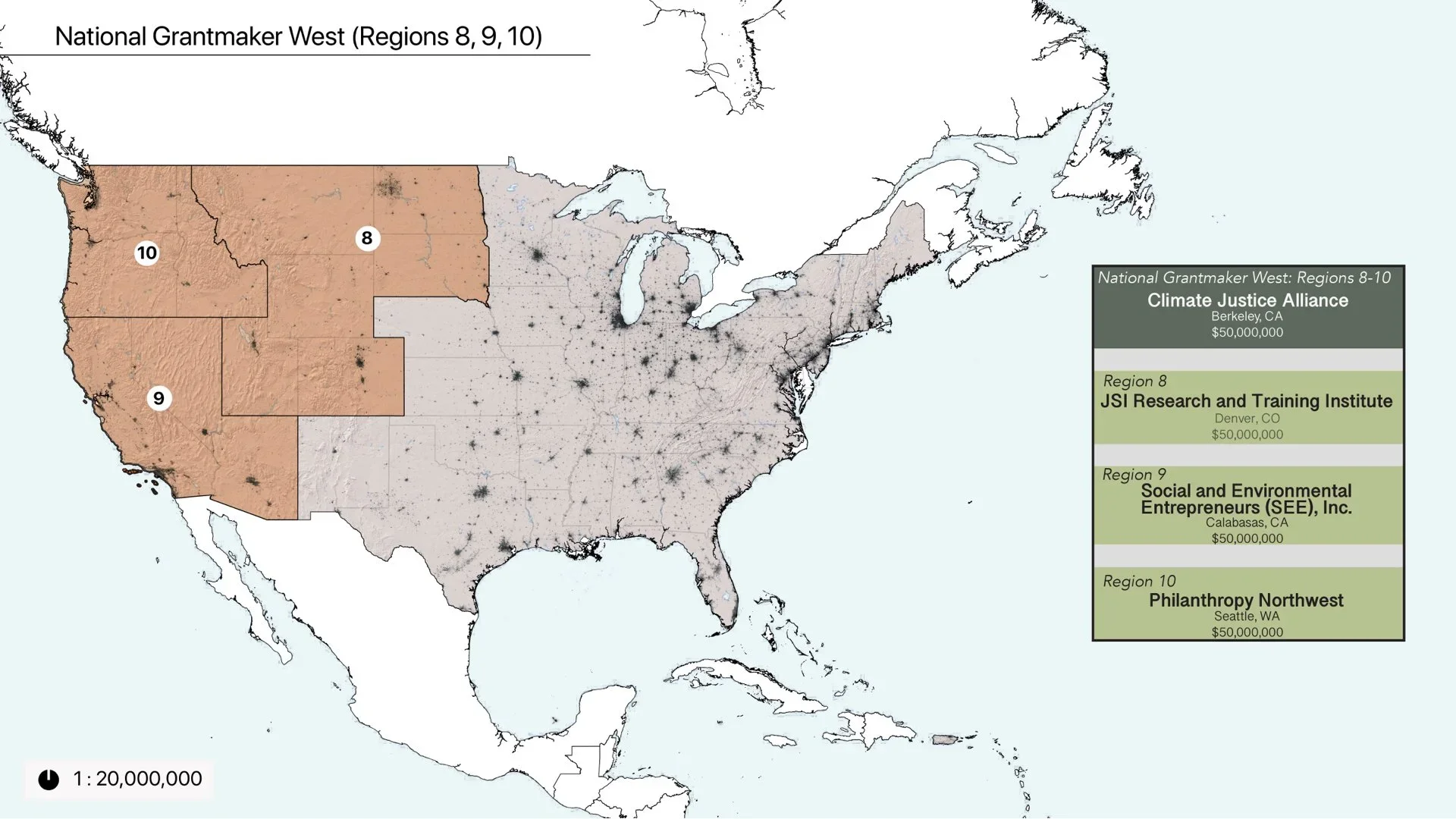

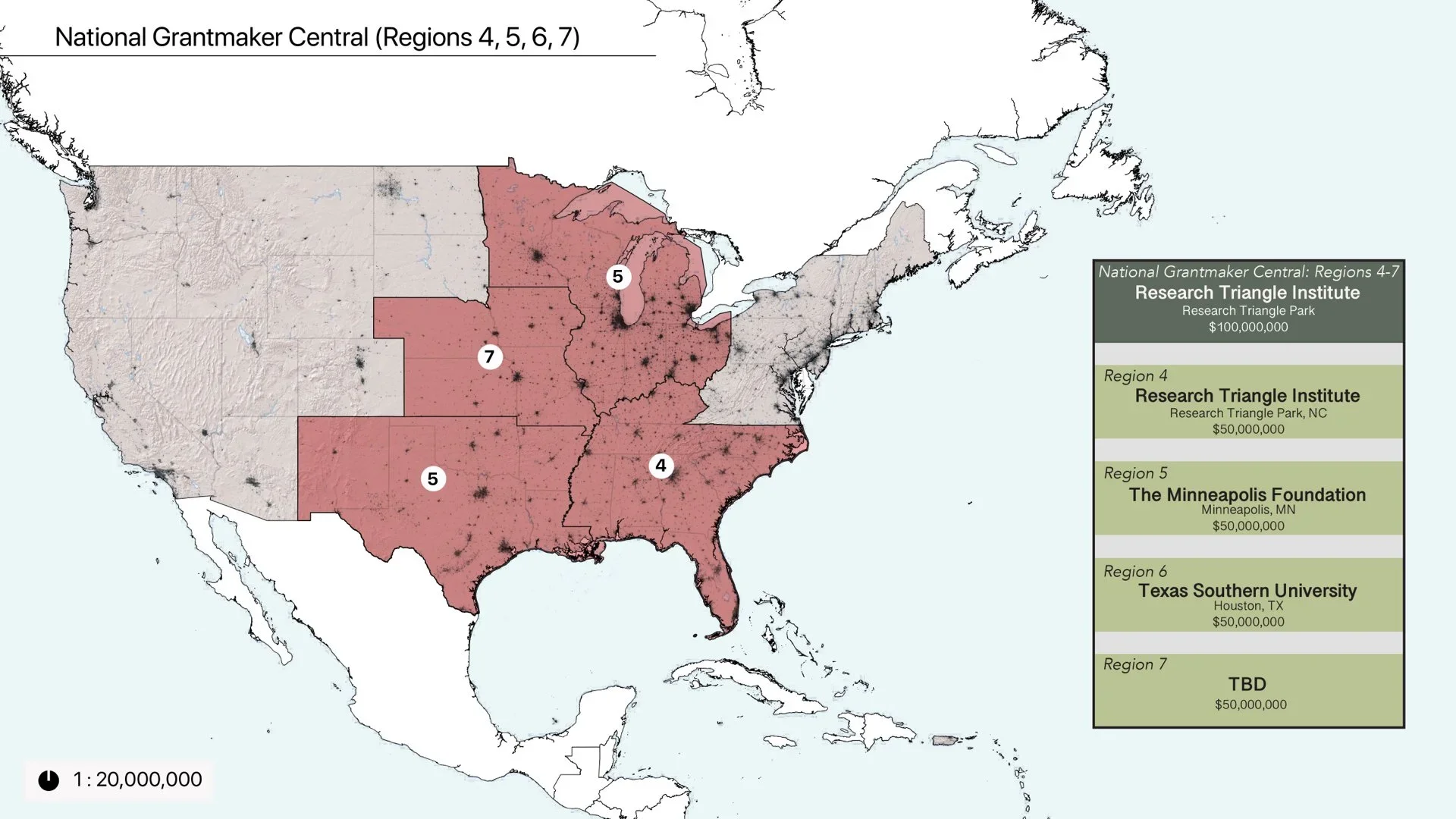

The TCGP was organized as a nationwide, multi-tiered network rather than a centrally administered EPA program. EPA delegated funding and oversight to a small number of national grantmaker partners, which in turn managed regional hubs and local subgrants across the country. This structure was designed to decentralize decision-making and reach frontline communities, but it also diffused accountability and made consistent standards difficult to enforce.

Fig 11.

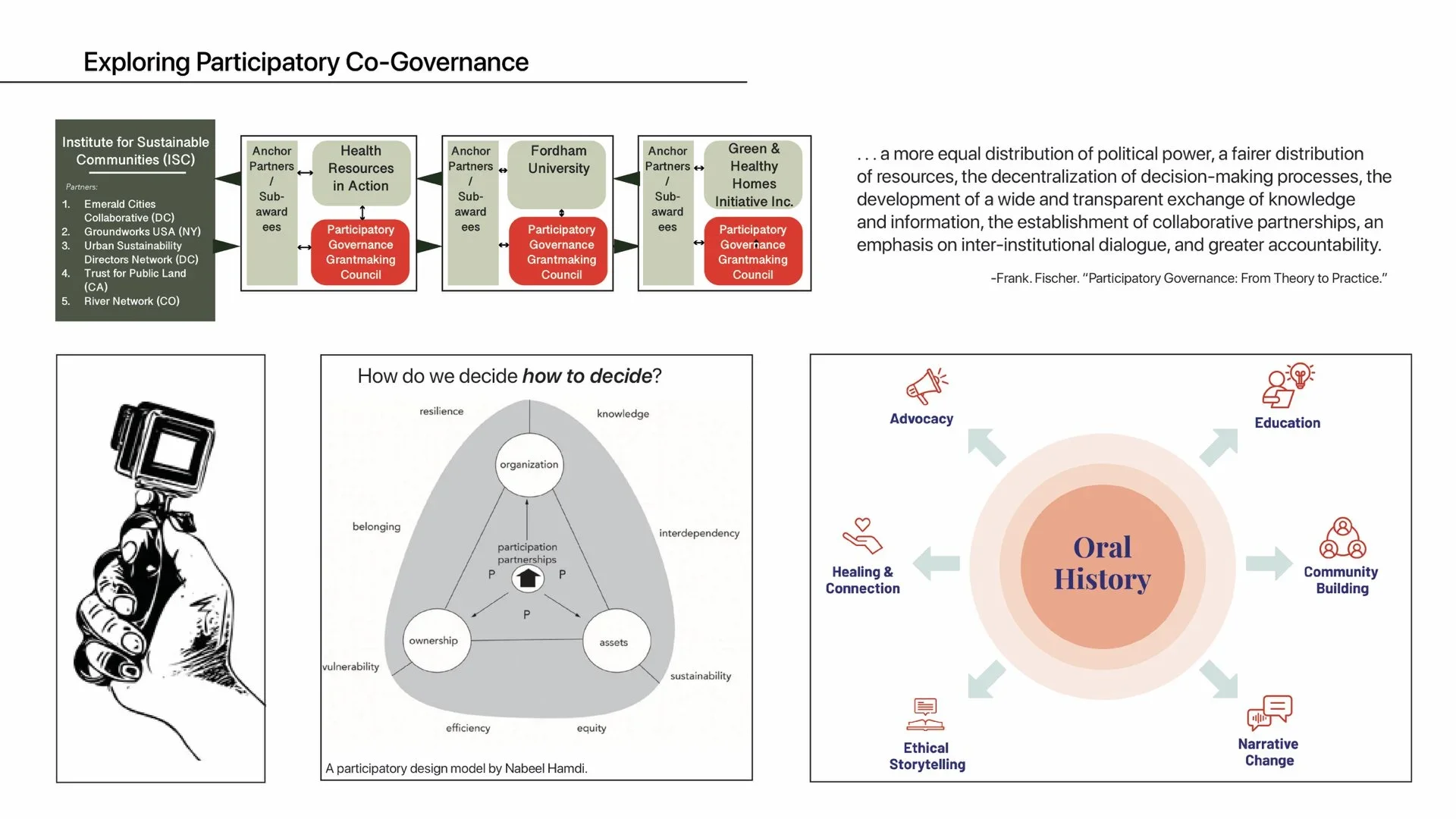

At the regional level, the TCGP relied on participatory co-governance structures to guide grantmaking decisions. National partners established regional hubs and advisory bodies intended to incorporate local knowledge, community priorities, and stakeholder input into funding allocations. While this model aimed to democratize decision-making, it also introduced variation in how criteria were interpreted and applied across regions.

Fig 12.

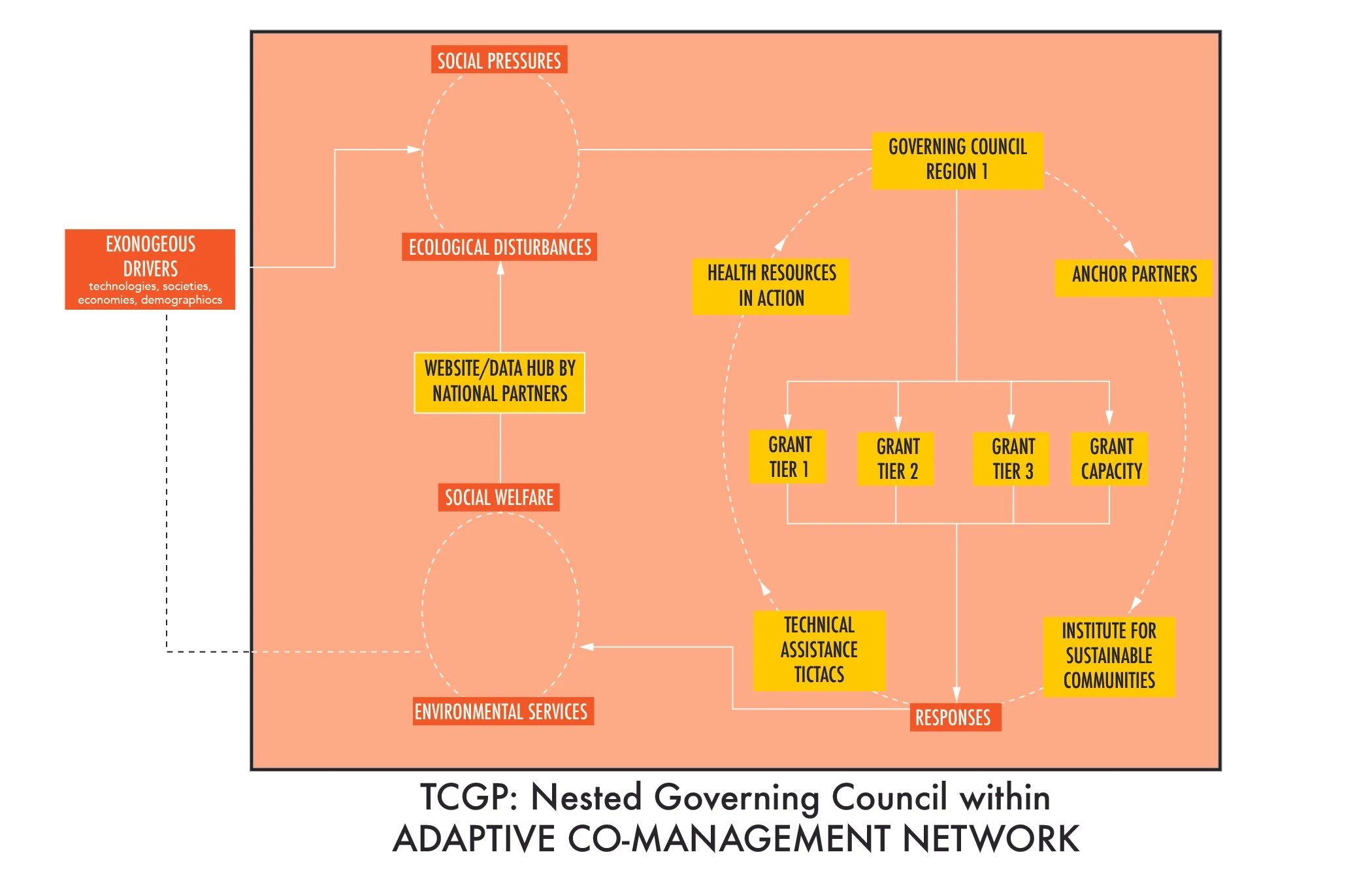

The TCGP functioned as an adaptive co-management network by distributing authority across interconnected hubs, nested governing councils, and community actors rather than relying on a single decision-making center. These regional networks were designed to learn and adjust over time through feedback loops, shared governance, and iterative grantmaking responsive to local conditions.

Fig 13.

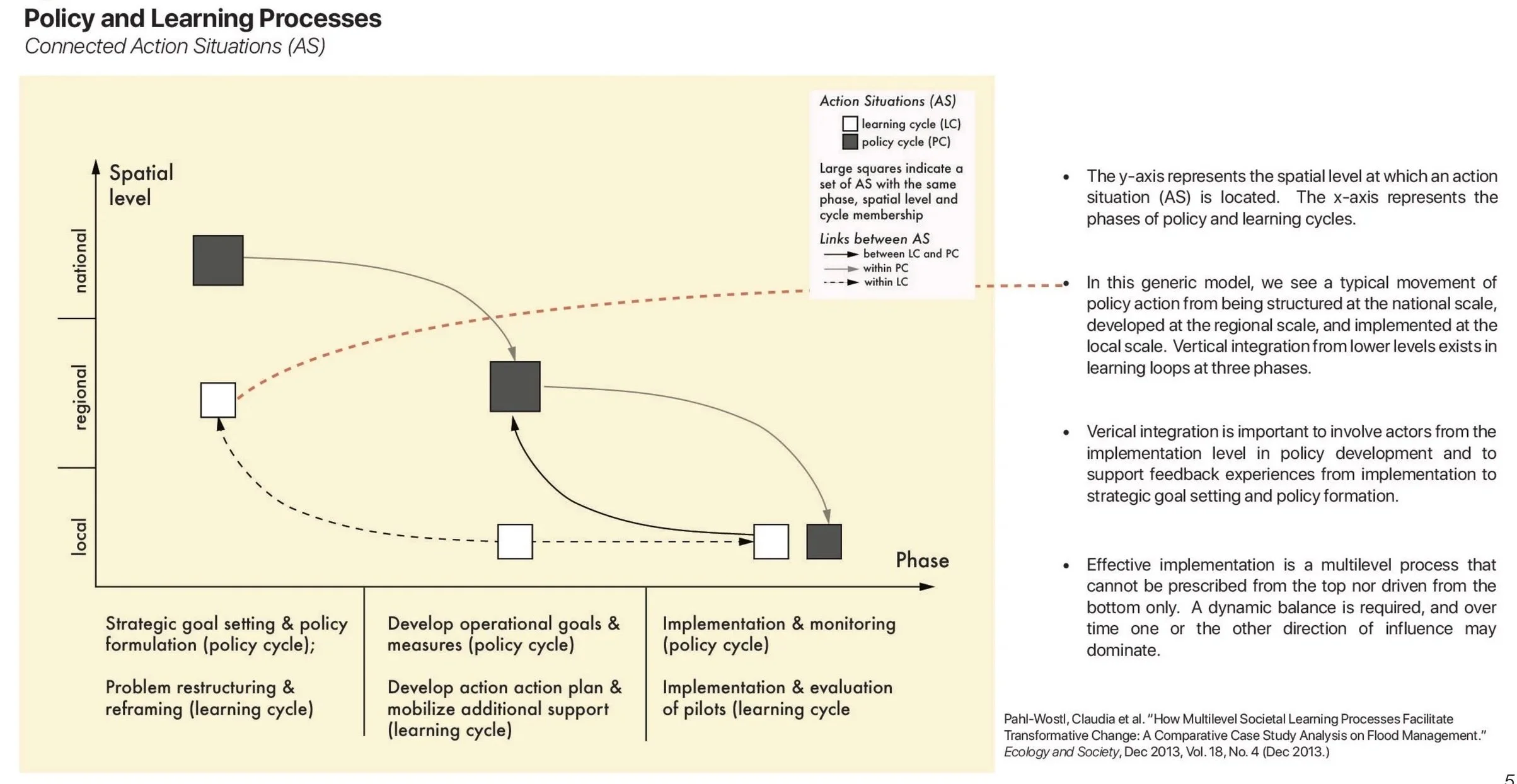

Feedback loops and loop learning (diagrammed here by Claudia Pahl-Wostl et al.) are central to environmental justice governance. Within the TCGP’s regional networks, information from grantees and communities was intended to move upward, shaping adjustments to funding criteria, technical assistance, and governance practices. In theory, lessons from early grant rounds would be incorporated into subsequent rounds, embedding learning directly into the program’s ongoing structure.

Fig 14.

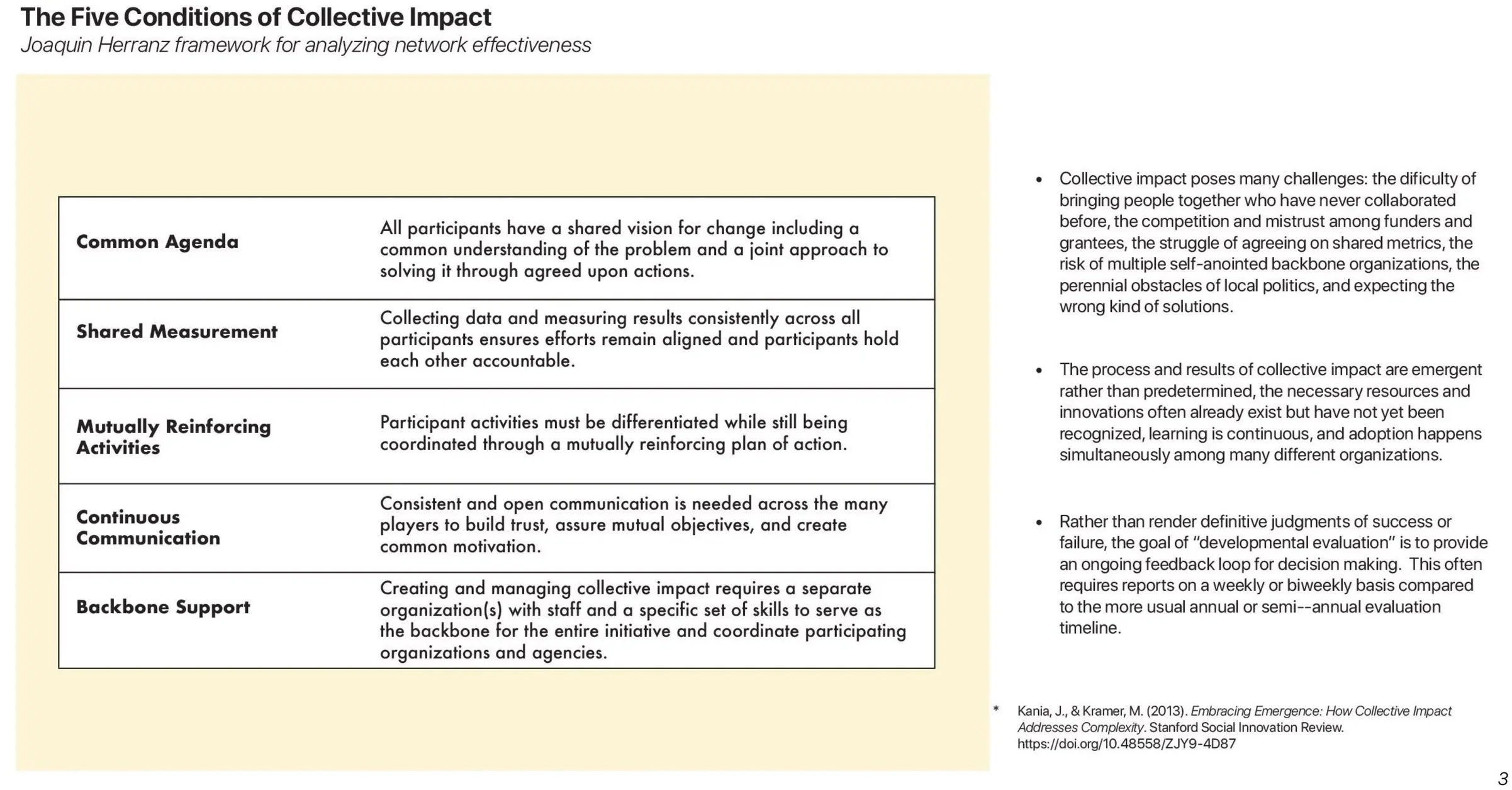

Joaquin Herranz’s concept of collective impact emphasizes sustained coordination, shared learning, and continuous communication among diverse actors working toward a common goal. The TCGP reflected this model by organizing networks of national partners, regional hubs, and community organizations around shared environmental justice outcomes rather than isolated projects.

Fig 15.

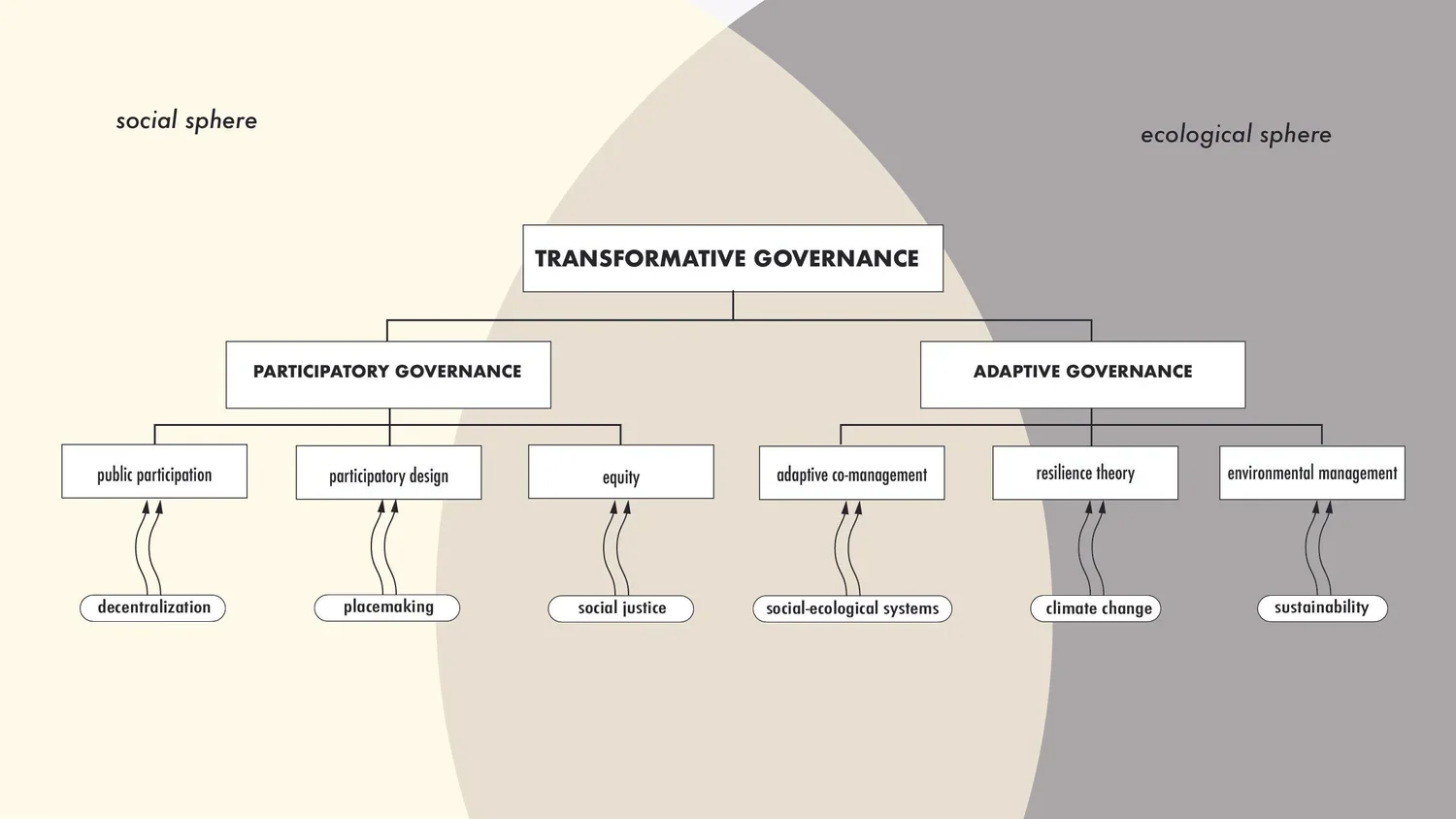

EJ governance can be understood as a form of transformative governance that emerges from the convergence of two traditions: participatory governance in the social sphere and adaptive co-management in the ecological sphere. From participatory governance, EJ governance inherits an emphasis on inclusion, shared authority, and the legitimacy of decisions shaped by those most affected. From adaptive co-management, it draws its commitment to learning, flexibility, and feedback-driven responses to complex social-ecological systems.

3. Duties of the National Grantmaker Partners

In theory, the duties of the National Grantmaker Partners were designed to decentralize federal power and elevate lived experience in decision-making. In practice, the partners operated in a mixed space—part federal contractor, part philanthropic-style grantmaker. This dual identity created ambiguities around accountability, especially regarding how decisions were made, how relationships influenced awards, and how transparent partners needed to be about internal review processes.

The program’s race-conscious mandate heightened these pressures. Partners were expected to prioritize communities impacted by racialized environmental burdens, while simultaneously avoiding any decision-making process that could be construed as explicit racial preference. This placed intermediaries in a complex administrative position: they were asked to center race as an analytic category, but not as a formal eligibility criterion. Many attempted to address this by relying on disadvantage indices, narrative assessments, and community scoring frameworks. Yet the lack of standardized criteria across partners created unevenness in implementation—and, as critics argued, opened room for informally networked decision-making that resembled established nonprofit ecosystems more than transformative EJ governance.

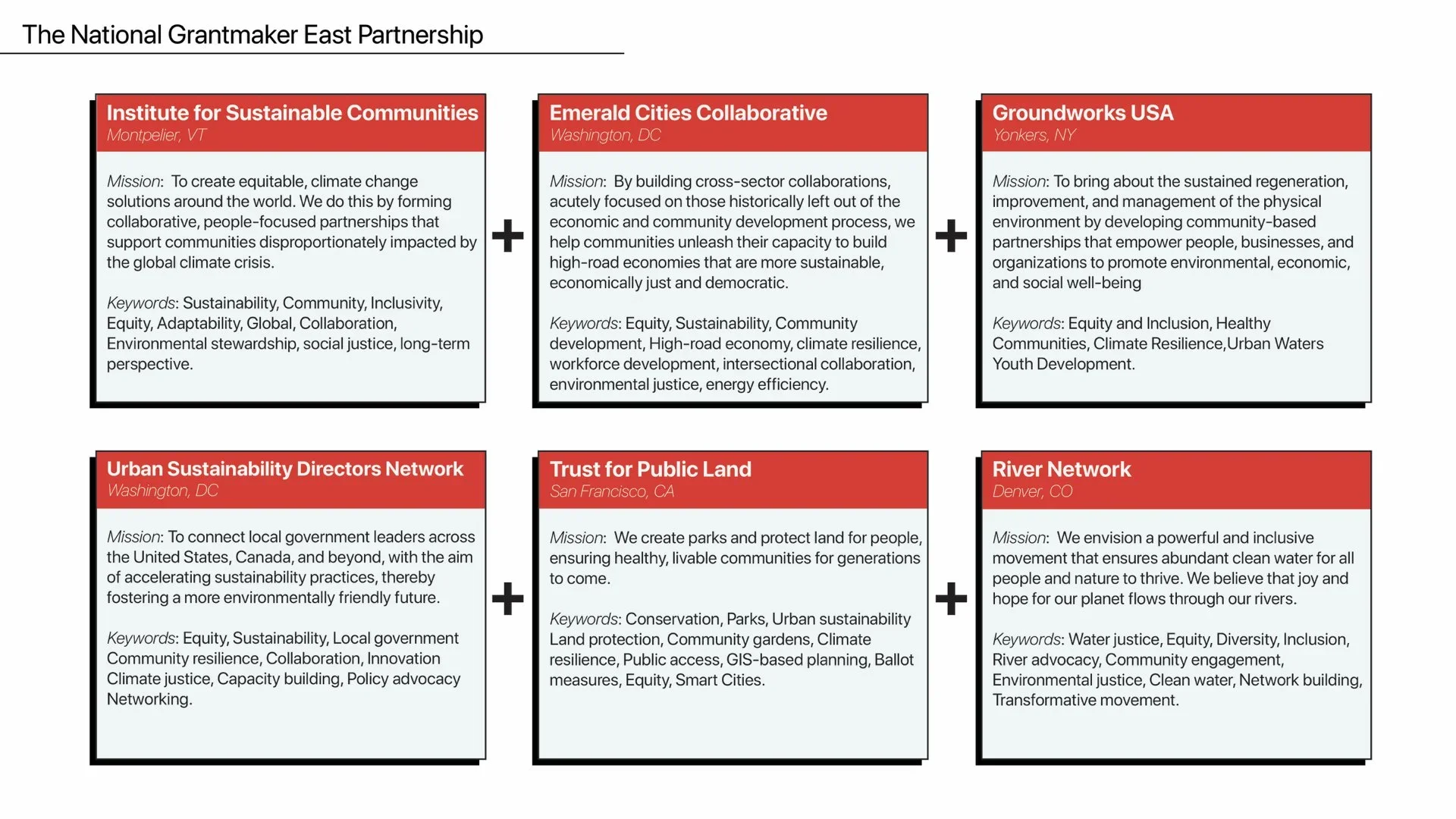

Fig 16.

Six national-scale nonprofits were subcontracted to run the TCGP—Institute for Sustainable Communities, Emerald Cities Collaborative, GroundworksUSA, Urban Sustainability Network, Trust for Public Land, and River Network—and were responsible for administering regional grantmaking hubs, providing technical assistance and capacity-building to local organizations, and coordinating participatory decision-making processes to advance EPA’s environmental justice objectives.

Six Duties of the National Grantmaker Partners

01_multi-scale outreach & networking

National Grantmaker Partners operate across scales. At the national scale, ISC and its partners lend support to the two other National Grantmakers (Central and Western) through a national website and data visualization hub. Also, ISC and its partners will engage with the EPA surrounding federal grant compliance. At the regional scale, ISC and its partners provide coordination services to the three Regional Grantmakers: Health Resources in Action (Region 1,) Fordham University (Region 2,) and Green & Healthy Home Initiative (Region 3.) At the community scale, ISC and its partners provide on-demand solution services to subawardee CBOs while collaborating on storytelling projects, translating impact stories with scale-specific messaging.

02_mentorship & organizational capacity-building

The role of the National Grantmaker Partners is largely self-determined, but most simply: the duties involve capacity-building for the program and its participants. The partnership is designed to interact with the program horizontally—emphasizing supporting the self-empowerment of frontline organizations. To do this requires a comprehensive communications effort to build relationships across the program. With Regional Grantmakers, the first priority is supporting the three Participatory Co-Governance Councils. Through TCTACs, community CBOs could be connected to National Partners with subject-specific expertise. There is also the opportunity to recruit CBOs into the program.

03_program development

The role of the National Grantmaker Partners is largely self-determined, but most simply: the duties involve capacity-building for the program and its participants. The partnership is designed to interact with the program horizontally—emphasizing supporting the self-empowerment of frontline organizations. To do this requires a comprehensive communications effort to build relationships across the program. With Regional Grantmakers, the first priority is supporting the three Participatory Co-Governance Councils. Through TCTACs, community CBOs could be connected to National Partners with subject-specific expertise. There is also the opportunity to recruit CBOs into the program.

04_research, data-tracking, and evaluation

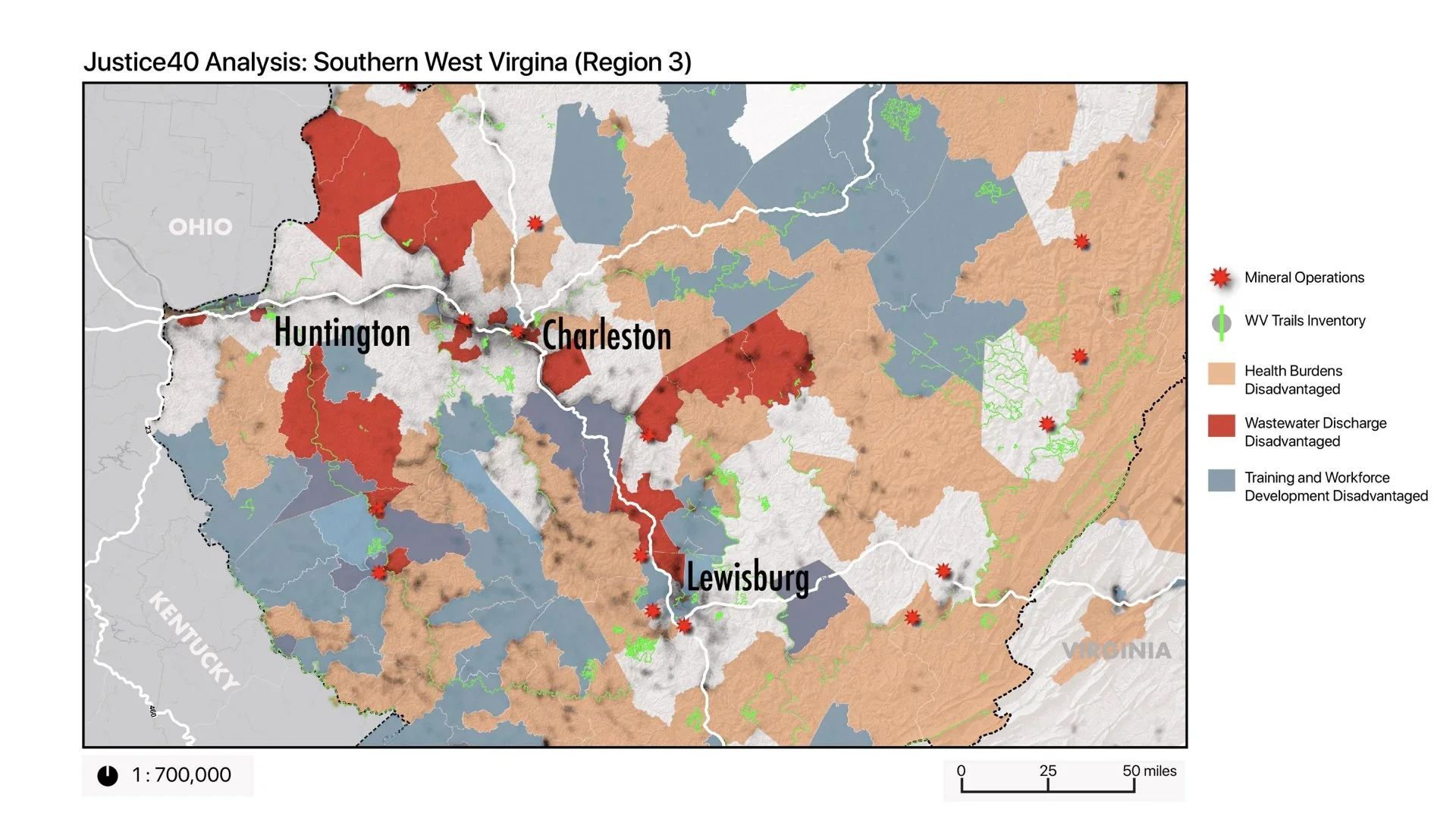

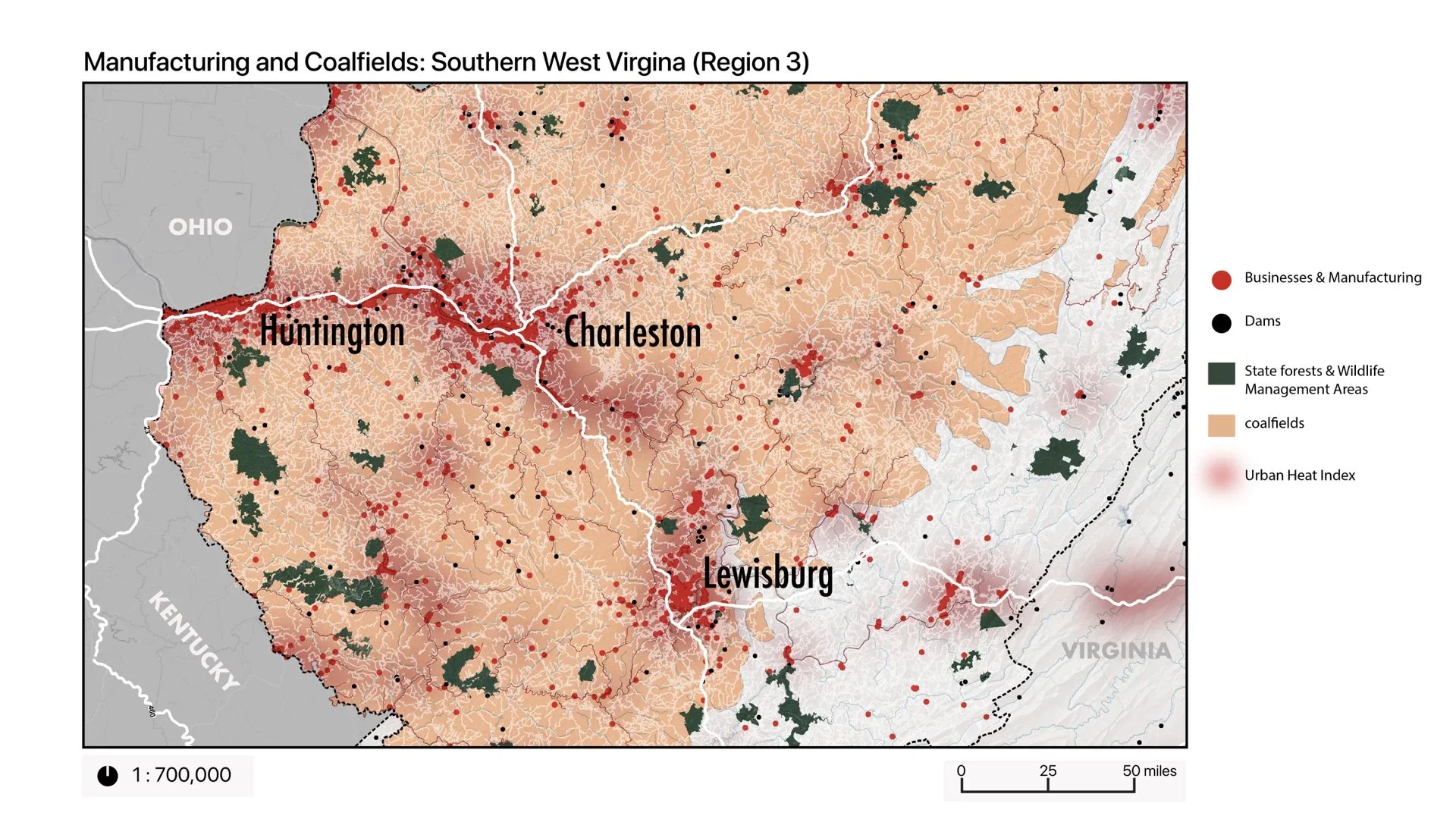

Across all connections, programs, and scales, ISC and its partners must straddle the development of equitable program with the evaluation of its impact. Whether it be working with the EPA on grant compliance, promoting bottom-up decision-making with Regional Grantmakers, or collaborating with local CBOs in co-developing communications media, National Partners must develop a dynamic storytelling collective that produces messaging aimed at diverse audiences. The Justice40 dataset should underpin this multi-scalar communications undertaking.

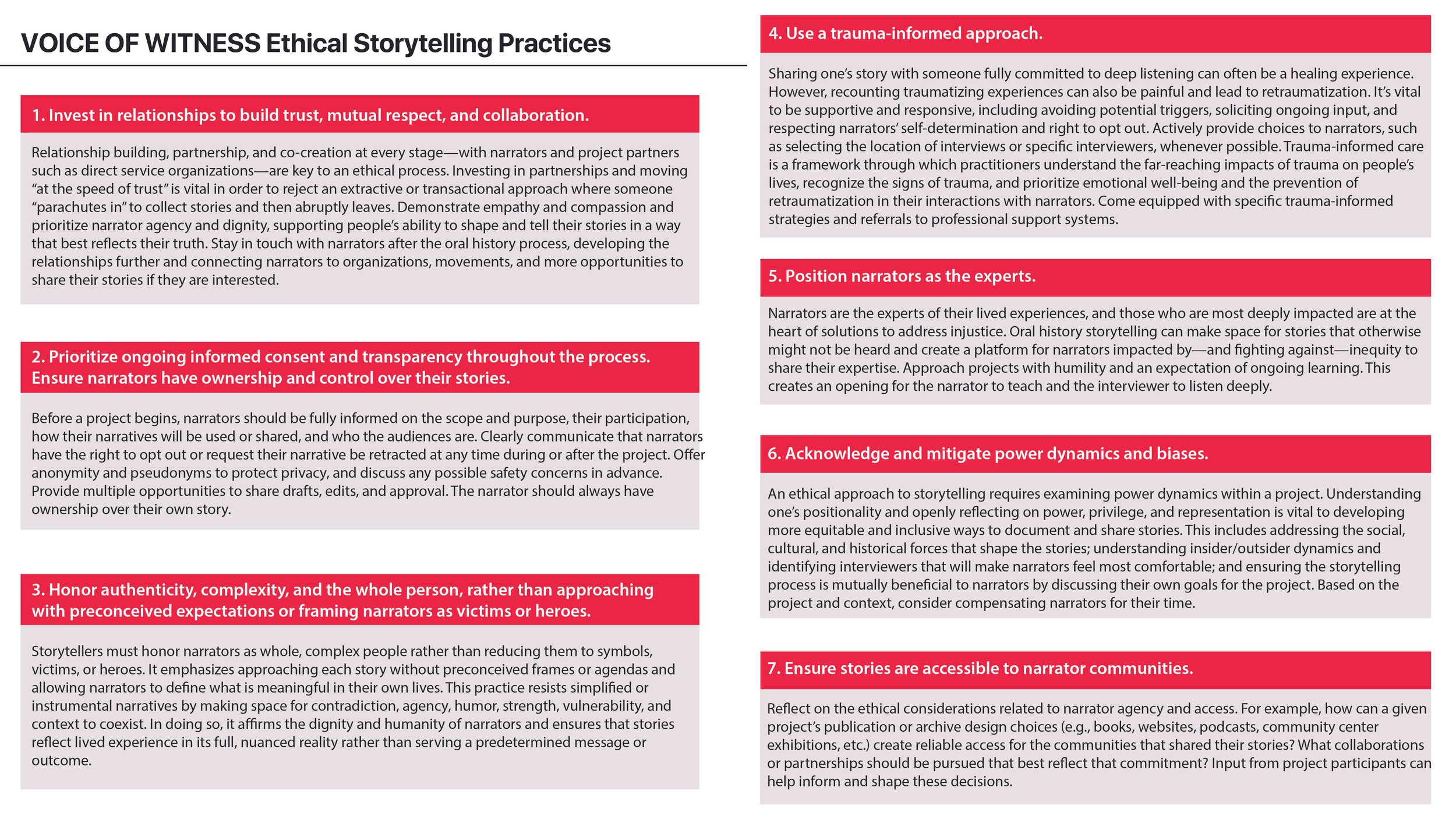

05_ethical storytelling

Ethical storytelling was a stated core principle of the TCGP, meant to ensure that communities could articulate their priorities, harms, and visions in their own words. This narrative-centered approach aimed to shift power away from federal metrics and toward community-defined understandings of environmental injustice. It also aligned with the program’s race-conscious orientation: stories illuminate lived experiences of racialized exposure, displacement, and exclusion in ways that quantitative indicators alone cannot.

06_filling in the gaps

Approximately 50% of the total TCGP budget is aimed at projects. The second 50% is directed toward organizations that support these projects by acting on the program horizontally, like the National Partners, Regional Partners, and TCTACS. These horizontal organizations are responsible for removing barriers for CBOS to enter the program, for supporting CBOs with project collaboration, and for supporting the self-empowerment of community-led co-governance councils. Such responsibilities demand tenacious outreach, active listening, and the collaborative development of adaptive strategies. Many of the duties of the National Grantmaker Partners will be emergent, responding to the needs of participants and advisory councils.

Fig 17.

Nested participatory co-governance networks in the TCGP distributed decision-making across national, regional, and local levels, enabling community-informed grantmaking while linking local knowledge to broader program goals and adaptive learning processes, while the National Partners provided overall coordination, accountability frameworks, and cross-regional learning to maintain coherence across the program.

Fig 18.

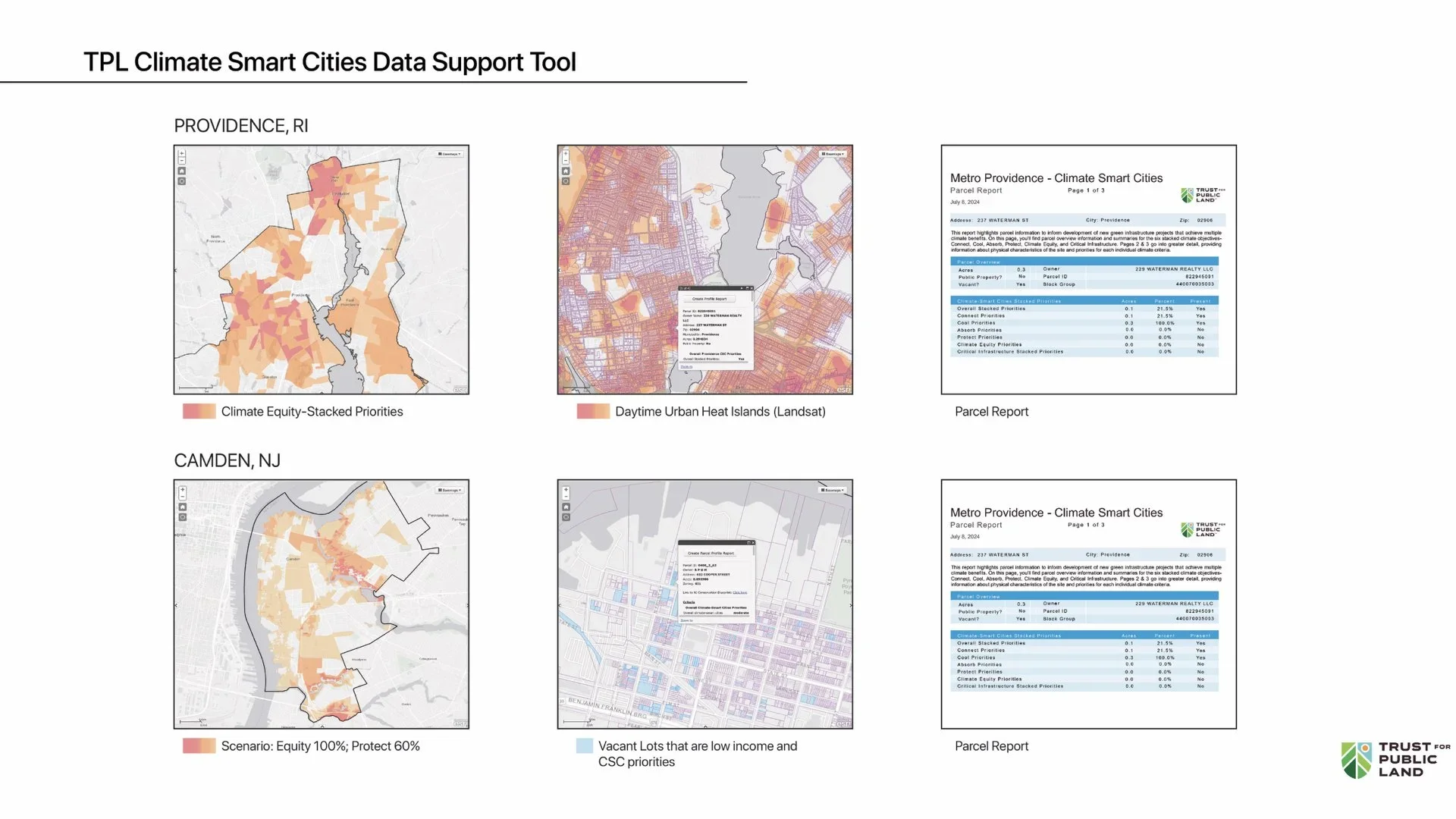

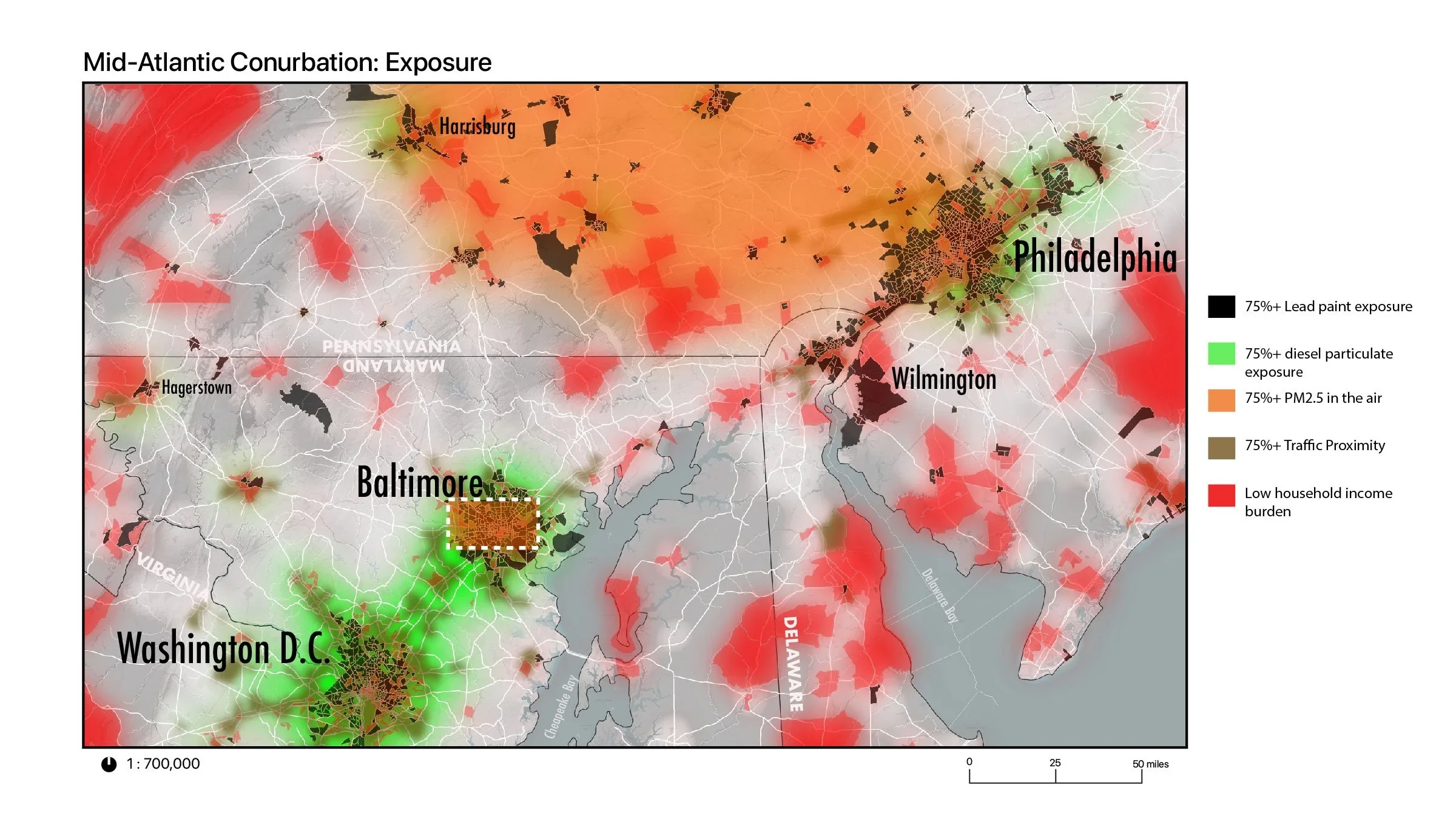

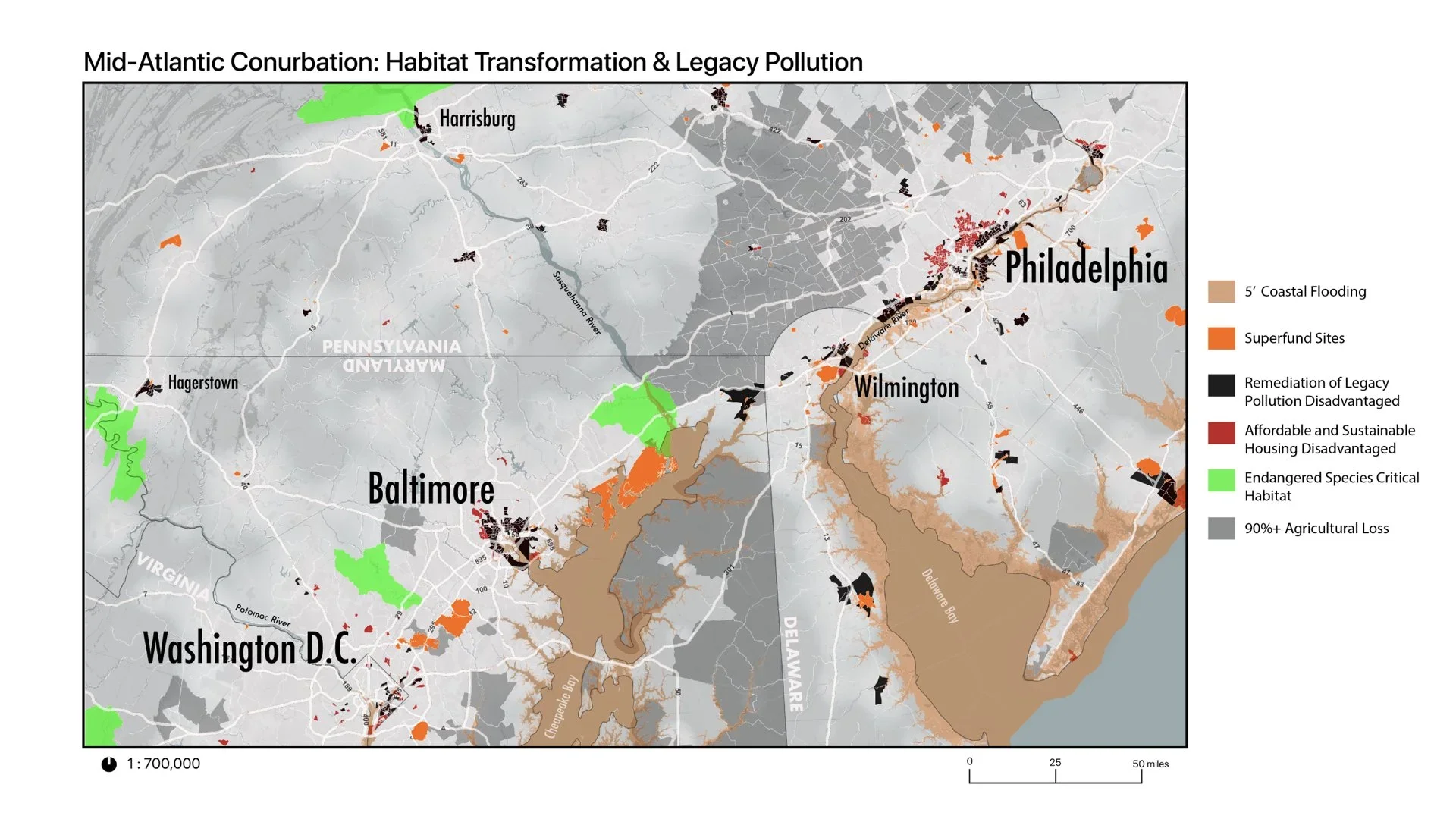

The Justice40 dataset played a central role in the TCGP by providing a standardized, race-neutral framework for identifying disadvantaged communities eligible for funding. It guided grant targeting by using indicators related to environmental burden, climate risk, infrastructure need, and socioeconomic vulnerability rather than explicit racial classifications. In doing so, the dataset was intended to align the program’s equity goals with legal constraints while promoting consistency and accountability across regions.

Fig 19.

The Justice40 dataset integrates a diverse set of exposure metrics—including air pollution, climate risk, legacy contamination, housing and infrastructure burden, and health vulnerability—to identify disadvantaged communities based on cumulative environmental and socioeconomic stressors rather than single indicators.

Fig 20.

The Justice40 dataset is grounded in the theory that cumulative disadvantage emerges from overlapping environmental, health, and socioeconomic stressors, and it supports layered decision-making by providing a shared, data-driven baseline that can be refined through regional expertise and community input.

Fig 21.

The dataset frames geospatial locations as layered landscapes of disadvantage by mapping how multiple burdens—such as pollution exposure, climate risk, infrastructure gaps, and health vulnerability—overlap in the same places, revealing cumulative impacts that are not visible through single metrics alone.

Fig 22.

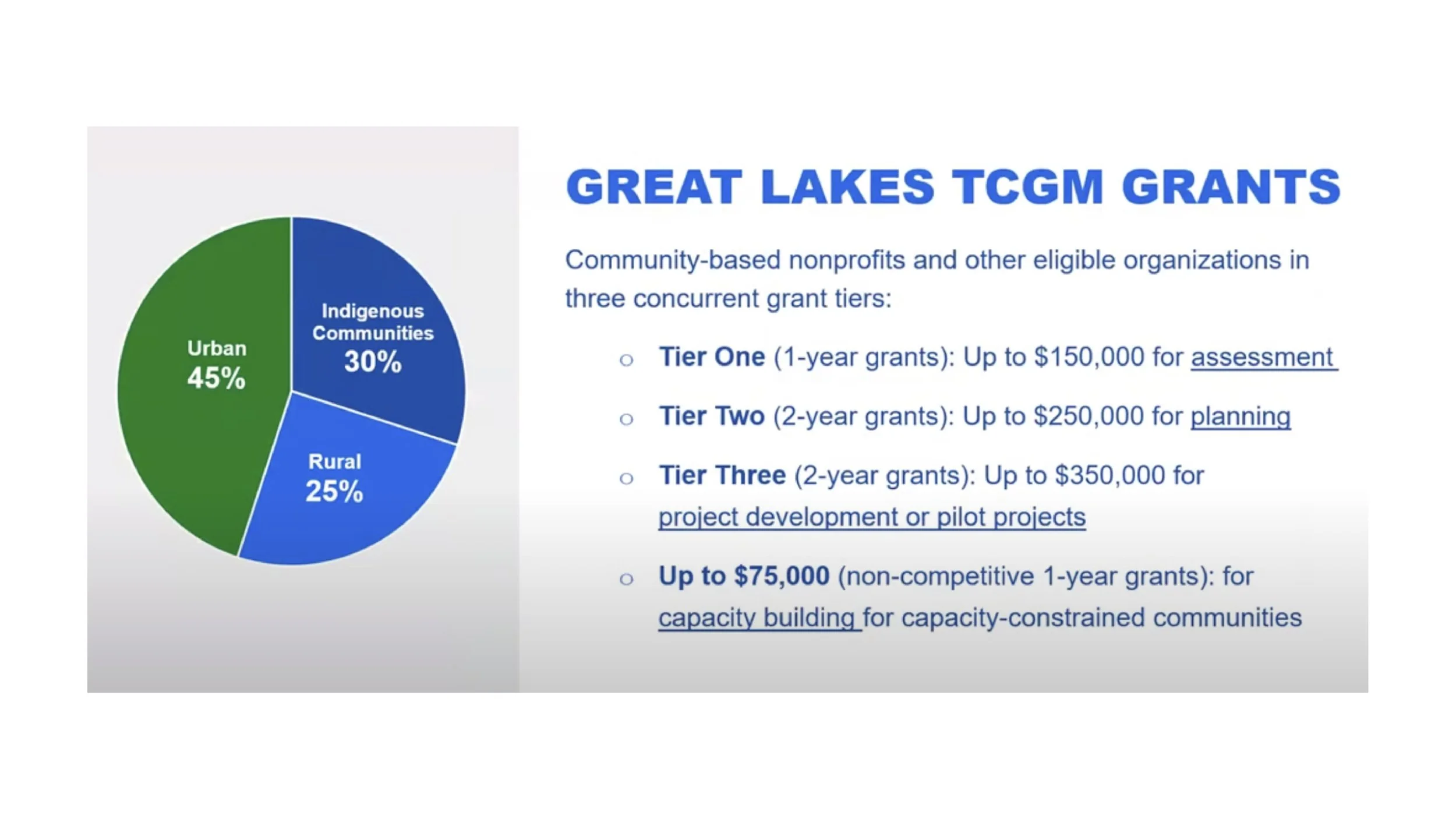

Some nonprofits tasked with TCGP’s implementation remained committed to racial categories. This racially-coded slide used in communications by the Great Lakes region might suggest that there were many different interpretations of the TCGP’s mandate.

Fig 23.

Ethical storytelling requires slow work, trust-building, and a willingness to relinquish narrative control. The program’s termination underscores a deeper lesson: participatory storytelling cannot be treated as an add-on to structurally conventional grantmaking. If intermediaries retain decisive authority, community narratives will always compete with institutional priorities. Sustaining truly bottom-up co-governance requires not only ethical storytelling methods but structural guarantees that community voice carries actual decision-making power.

Fig 24.

In ethical environmental justice storytelling, overlapping identities between the narrator and the story collector can enable trust and deeper disclosure. This relational proximity shapes whose experiences are shared, how they are interpreted, and whether communities feel represented rather than extracted from. It suggests that identity matters not only as a marker of disadvantage, but as a conduit for legitimacy, empathy, and power in EJ work. Thus, many questions emerge about the future legal feasibility of EJ projects in the public sector.

4. Insights

My relationship to the Thriving Communities Grantmaking Program is best described as ambivalent. Conceptually, the program represents the most sophisticated federal attempt I have seen to operationalize what I have long thought of as environmental justice or transformative governance: decentralizing authority, embedding participation, and treating communities as active partners in decision-making rather than passive recipients of aid. These ideas have shaped my work for years, beginning with my exposure to adaptive co-management through Stephen Lansing’s research on the Balinese subak system and extending through my own academic projects exploring how decentralized working groups might govern complex environmental landscapes. From that perspective, the TCGP felt like a rare and serious effort to translate theory into practice at a national scale.

At the same time, my proximity to the program’s implementation revealed challenges that complicated this initial enthusiasm. As I pursued professional opportunities connected to the program and engaged with organizations responsible for its administration, I observed how participatory governance models can strain under institutional realities. The Justice40 framework was designed to target disadvantage using place-based, cumulative, and material indicators, in part to remain consistent with evolving legal constraints around race-conscious decision-making. Yet in practice, some implementing organizations appeared to place greater emphasis on identity-based approaches rooted in their own institutional missions. This created tension between the program’s legal architecture and its day-to-day execution, particularly around hiring, prioritization, and definitions of community representation. Whether this reflected insufficient training, differing interpretations of the mandate, or deeper philosophical commitments, it introduced ambiguity and risk into an already complex governance experiment.

When the program unraveled following the election, my response was mixed. I was disappointed to see a promising governance model curtailed so quickly, but I also came to understand how unresolved legal, institutional, and political tensions made its continuation fragile. What stood out to me was not malice or bad faith, but a strong moral confidence among many participants that their interpretation of justice justified broad discretion. That confidence, when combined with public funding and decentralized authority, raised difficult questions about accountability, neutrality, and the appropriate limits of delegated power.

These experiences prompted me to reassess my own orientation toward environmental justice work. I remain deeply committed to ecological resilience and participatory governance, but I have shifted my focus toward what I describe as service change: working within existing economic and legal structures to redistribute resources, strengthen livelihoods, and improve material conditions in ways that are durable and defensible. This is not a rejection of justice-oriented goals, but a recalibration of how I believe they can be responsibly advanced.

More broadly, I have come to see governance not as a binary between top-down and bottom-up systems, but as a layered and hybrid process. Effective and equitable decision-making often requires balancing centralized capacity with decentralized input, efficiency with inclusion. As economic inequality increasingly defines the terrain of injustice, I am persuaded that durable progress will depend on material empowerment as much as — if not more than — symbolic alignment. For now, that means working within a profit-based system to move resources, rebuild value chains, and give marginalized communities the tools to sustain themselves. If deeper systemic change ever arrives, it will likely emerge from that material foundation.