ABANDONING MANIPULATION:

Maya Deren in Haiti, 1948-1953

by Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (2.4 MB)

© 2017 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

Originally published in MIT University’s Setting A Performative Frame (2017)

Abstract

This article examines Maya Deren’s evolving philosophy of filmmaking, tracing her shift from experimental, ritual-inspired cinematic theory to an ultimately abandoned attempt to represent Haitian Voudou on film. It argues that Deren’s confrontation with the metaphysical integrity of Haitian ritual challenged her belief in cinema’s transformative power, pushing her toward ethnographic writing instead. The piece situates this turn as both an artistic crisis and a self-reflexive gesture that illuminates the limits of film, the ethics of representation, and Deren’s enduring mystique.

Abandoning Manipulation

Experimental filmmaker Maya Deren died at forty-four with rumors of a Voudou curse veiling the circumstances of her death. Throughout her short career, she made ten films, wrote extensively on filmmaking, and cemented herself as a filmmaking personality of mythical proportions. In “Maya Deren: A Life Choreographed for Camera,” Mark Alice Durant writes: “The aura that suffuses Deren’s biography emanates partly from the enigmatic power of her films, but it has been magnified by her bohemian glamour and visionary intelligence, edged with a hint of tyranny.”

Indeed, Deren was an outspoken theoretician, deeply engaged in revolutionizing filmmaking forms. Her film work spans fictional and nonfictional source material, but with both, she emphasizes filmmaking as a creative process, lambasting the observational shortcomings of the documentary film genre in 1946’s An Anagram of Ideas on Art:

He [the documentary filmmaker] is further limited by a set of conventions which originate in the methods of the scientific film. He must photograph “on the scene” (often a very primitive one) even when material circumstances may hamper his techniques, and force him to select the accessible rather than the significant fact. He must use “real” people, even if they are camera-shy or resentful of him as an alien intruder, and so do not behave as “realistically” as would a competent professional actor.

For Deren the documentary filmmaker’s preoccupation with reality is self-defeating. Instead, she suggests a creative, interpretive treatment of filmmaking subjects. Daren’s films are occupied with ‘depersonalized characters,’ who express themselves exclusively through gestural body language. She theorized that this depersonalization enlarged the characters “beyond themselves,” setting them free from the “specializations and confines of personality.“ In “Cinema as an Art Form,” she writes:

The dislocations of modern life are, precisely, dislocations of reality itself. And it is conceivable that an individual should be incapable of a distortion of vision which, designed to complement and “correct” these dislocations of reality, results in an apparent “adjustment”... Cinema, with its capacity for animating the ostensibly immobile, is especially equipped to deal with such experiences.

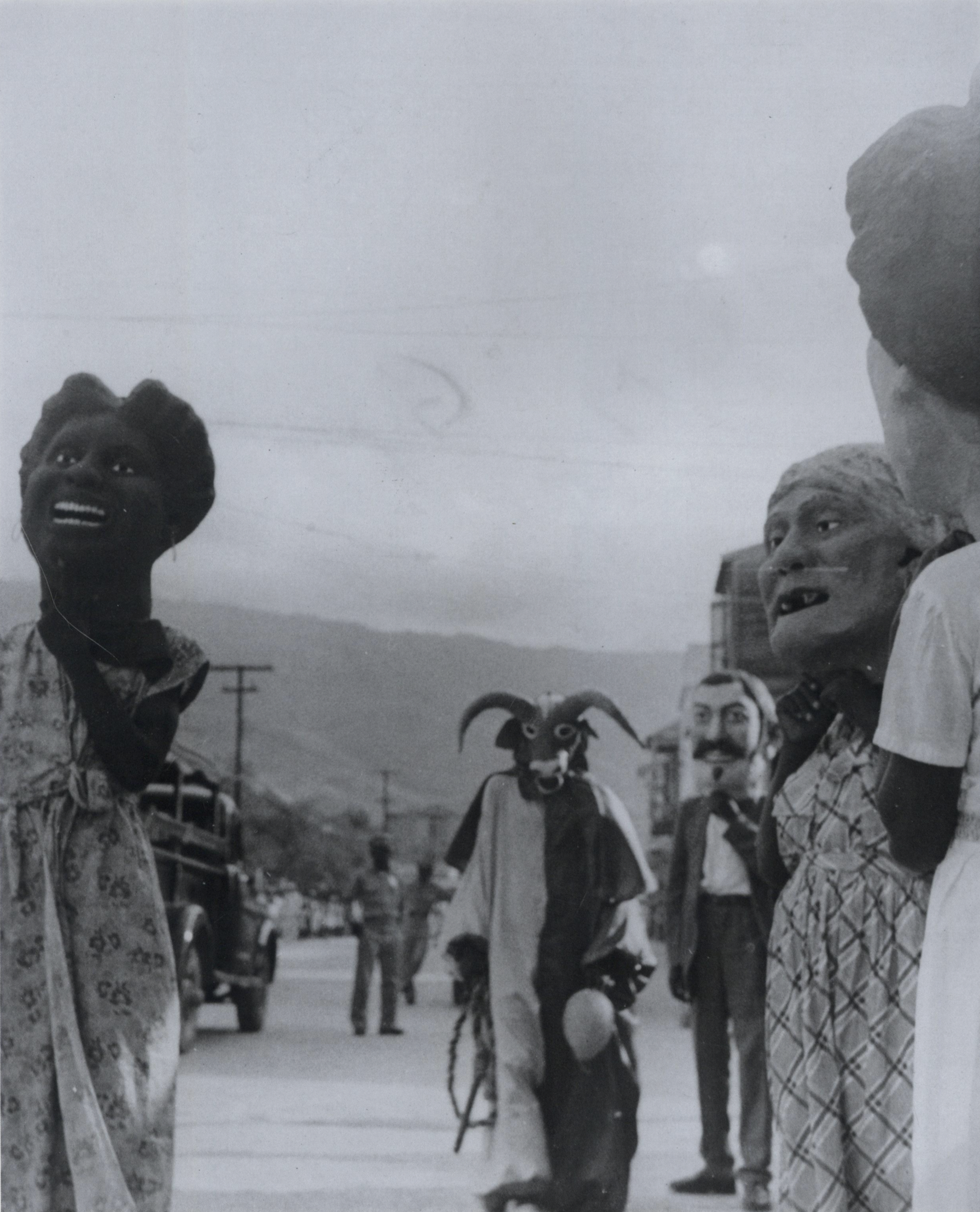

Fig 1

Maya Deren, Untitled, Haiti, 1948-55

With camera as artistic instrument, Deren’s films were exercises in consciousness, and she called her film aesthetic ‘ritualistic form.’ Deren adamantly believed in a film’s capacity to transform viewers on an interior, subjective level. In such, Vicky Gagnon suggests Deren’s films and writing communicate a moral prerogative. In “At the Crossroads: Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen Project,” Gagnon writes: “[Deren] considered the ability to understand, or to know the reality in which we live, to be a problem of perception that could be corrected by the ritualistic form she proposed in film.”4

In 1946, Deren turned her ritualistic filmmaking process to the subject of ritual itself, prodding her conceit that “all ritual activity was universal.”5 Funded by the first-ever Guggenheim grant for creative filmmaking, Daren aimed her camera at non-fictional material, proposing a “cross- cultural fugue using ritual gestures and objects” that would intercut segments of children playing games in New York City and Haitian and Balinese dance rituals. She sailed for Haiti in 1948 and filmed 7000 feet of footage. Of this first trip, she notes: “My observations... completely support the whole theory of ritual game relationships upon which the film as a whole is based and which inspired the idea of constructing a film in the form of a visual fugue.”6

However, in the editing room, Deren faced an artistic crisis of misrepresentation. By cross- cutting Balinese and Haitian dance, each ritual became abstracted from its proper context. To combine both sacred forms into a visual fugue would misappropriate the divinity inherent in each practice. In an application for the renewal of a fellowship, she writes:

The editing of these films represents a problem which challenges me as an artist... The dances and the ritual itself - that which is visible - has meaning only within the context of the metaphysics - which is invisible. These dances are not performed for an audience of men or in order to convince them. They take place among men already convinced, and they are addressed to divinity. Moreover, a great deal of their intelligence depends upon participation. To an uninformed, a non-participating audience, the purely visual will carry the wrong meanings. The usual informative style of documentary and travelogue commentaries ais [sic] , in my opinion, inadequate to compensate for the detachment of the audience.7

This statement marks a departure from a filmmaking process that emphasized the formal manipulation of filmic elements. Here, she seems preoccupied with visible and invisible realities... and the camera’s inability to capture them. Concerned with the potential for her film to miscommunicate “wrong meanings” to an “uninformed, non-participating audience,” she seems to become a disinclined ethnographer:

I had begun as an artist, as one who would manipulate the elements of a reality into a work of art in the image of my creative integrity; I end by recording, as humbly and accurately as I can, the logics of a reality which had forced me to recognize its integrity, and to abandon my manipulations.8

Applying for money to return to Haiti, in 1948 she wrote: “I feel that it would be irresponsible of me to abandon this material simply because it did not turn out to lend itself to my personal ambitions as a creative filmmaker.”9 Returning to Haiti multiple times in the following years, Deren ended up shooting 5400 feet of film surrounding Haitian dance and Voudou, but even an ethnographic approach aimed at revealing the metaphysical dimensions of Voudou proved inadequate. Ultimately, she abandoned the film entirely, and in its place published an anthropological text Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti in 1953.

What was it about the integrity of this reality that forced Deren to abandon film in exchange for the written word? Perhaps she felt uncomfortable applying her theory of depersonalized characterization upon Haitian participants. Perhaps she simply chose the wrong source material to explore her conceits. “It is curious,” writes Durant, “that the moving image failed Deren in her attempt to represent a real-world phenomenon of depersonalization; it was, she felt only through still imagery and written language that Voudou could be adequately described.”10

As a anthropological text, Divine Horseman falls short of being experimental. Visual anthropologist Lucien Taylor calls it a “very conventional book that was nothing exceptional by anthropological standards of that time.”11 But as a written text instead of a film, perhaps Deren found a format where she was able to represent the su bject and context that her film footage failed to reconcile: herself and her filmmaking. I regard this self-reflexivity as as a bold artistic gesture, and it is certainly the stuff of legend. She writes: “I am interested in the relationship of the unreal to the real, in the manifestation of the unknown in the known; in discovering the laws of the unknown forces which compulse the universe.”12

In 1961, weakened by a dependence on amphetamines, Deren died of a brain hemorrhage brought on by extreme malnutrition. Her ashes were scattered at Mount Fuji.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

—1 Deren, Maya. An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Film and Form, 34.

—2 Deren, Maya. “From the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947,” October 14, 24.

—3 Deren, Maya, “Cinema as an Art Form.” Reprinted in Clark and al., The Legend of Maya Deren: A Documentary Biography and Collected Works: Chambers, 320.

—4 Gagnon, Vicky Chainey. “At the Crossroads: Maya Deren’s Divine Horsemen Project”, (York University, Toronto Canada) 49

—5 Gagnon, 58

—6 Deren, Maya. “Summary of Activities Since Fellowship Award of 1946,” 4.

—7 Deren, Maya. “Application for a Re-Newal of a Fellowship in Motion Pictures,” 3.

—8 Deren, Maya. “From the Notebook of Maya Deren, 1947,” October 14, 21- 22

—9 Deren, Maya. “Theme and Form of Film-in-Progress” [Guggenheim Application 1946].

—10 Durant, Mark Alice. “Maya Deren: A Life Choreographed for Camera,” Aperture, No. 195 (Summer 2009) 46

—11 Taylor, Lucien. “From Verite to Virtual: Conversations on the Frontier of Film and Anthropology” (Watertown, MA: Documentary Educational Resouces.)

—12 Deren, Maya. “Untitled Notes.” Reprinted in Clark and al., The Legend of Maya Deren: A Documentary Biography and Collected Works: Chambers, 142.