TARGETING NEONICOTINOID-COATED SEEDS FOR BIRD CONSERVATION

By Malcolm Wyer

Click for report: full PDF (635 KB)

© 2024 Malcolm Wyer. All rights reserved.

ABSTRACT

This article examines the ecological and regulatory challenges associated with the widespread use of neonicotinoid-coated seeds in global agriculture, particularly their harmful impacts on bird populations and broader ecosystem health. It reviews scientific evidence showing that neonicotinoids—systemic insecticides applied as seed coatings—can be toxic to birds both directly through ingestion of treated seeds and indirectly contaminating habitats. The paper highlights regulatory shortcomings, especially in the United States where coated seeds remain exempt from stringent pesticide oversight, and discusses integrated pest management (IPM) and alternative agricultural practices as strategies for reducing neonicotinoid dependence. By linking declining bird abundance with pesticide exposure, the article advocates for targeted conservation efforts and policy reforms to mitigate risks to avian biodiversity and strengthen environmental stewardship.

INTRODUCTION

Birds have played a powerful role in the history of pesticide regulation. The link between DDT contamination and bald eagle eggshell thinning participated in the EPA banning the use of DDT in 1972.¹ The outsized role that birds play in food webs means that healthy bird populations are powerful indicators of large-scale environmental health. Further, the large spatial scales of bird monitoring studies exceed that of any other animal group², positioning birds as central protagonists in the study of ecotoxicology. Indeed, bird monitoring data paints a grim picture: long-term surveys “reveal a net loss in total abundance of 2.9 billion birds across all biomes, a reduction of 29% since 1970.”

Steep declines in North American bird populations parallel patterns of avian declines emerging globally. In particular, depletion of native grassland bird populations in North America, driven by habitat loss and more toxic pesticide use in both breeding and wintering areas, mirrors loss of farmland birds throughout Europe and elsewhere. Even declines among introduced species match similar declines within these same species’ native ranges. Agricultural intensification and urbanization have been similarly linked to declines in insect diversity and biomass, with cascading impacts on birds and other consumers. Given that birds are one of the best monitored animal groups, birds may also foreshadow a much larger problem, indicating similar or greater losses in other taxonomic groups.³

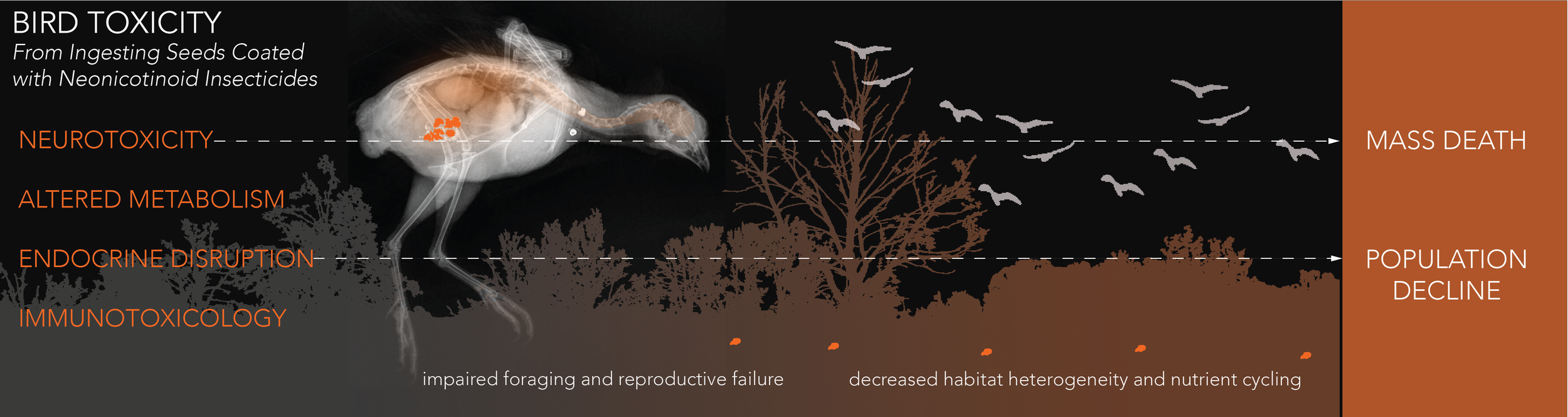

ABC’s The Impact of the Nation’s Most Widely Used Insecticides on Birds (2013) targets neonicotinoid insecticides as the most significant pesticide contributing to the estimated death of 100 million birds every year in the United States.⁴ Neonicotinoids are neurotoxins, functioning as effective pest control by attacking the nervous system of arthropods, blocking receptors, and at high doses causing paralysis or death. Introduced in the 1990s as a less toxic alternative to organochlorines and carbamates, they were praised for their supposed low toxicity transfer to vertebrates. Today, neonicotinoids are the most widely used insecticide globally, and loud calls for stricter regulation are coming from scientists and conservationists alike. Neonicotinoids persist and accumulate in soil; typically more than 90% of the active ingredient enters the soil with a half-life ranging from 200-1000 days.⁵ From there, neonicotinoids “readily leach so that significant levels might be predicted in groundwater and run-off immediately after application, particularly if there is heavy rainfall at this time, where the soil organic content is low, and on steep slopes.⁶ Of most urgent concern is their lethal effect on pollinators, soil-dwelling insects, benthic aquatic invertebrates, and granivorous vertebrates like birds.⁷

Authors Mineau et al. make a compelling case for the specific targeting of seed dressing/coating as the most lethal application of neonicotinoids for birds. “The contamination of avian foods such as insects or weed seeds from spray applications…pales in comparison to the risk from treated seed.”⁸ While negative effects from neonicotinoid spray applications may be mitigated through proper application methods, “avian exposure to high numbers of treated seeds cannot be prevented even if the product is applied at recommended rates using proper equipment.”⁹

Seed-eating vertebrates like many birds can consume a lethal dose of neonicotinoid coated seeds in a matter of minutes, and a UK study into neonicotinoid seed consumption by the grey partridge reveals devastating evidence. A grey partridge eats the equivalent of ~600 maize seeds per day, and it would only need “to eat ~5 maize seeds, six beet seeds, or 32 oilseed rape seeds to receive an LD50.”¹⁰ Even when not lethal, the acute toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides has been linked to bird immune suppression, reproductive problems, and the extreme loss of insect biomass and the toxicity of aquatic invertebrates as food sources.

What is being done to counter the dominance of neonicotinoids in global agriculture? On one front, there exists a regulatory battle, waged with new scientific research and the lobbying for better regulatory measures by the EPA. That is where I will begin. From there, I will discuss integrated pest management (IPM) and on-the-ground efforts to promote crop yields without the use of neonicotinoid coated seeds.

REGULATORY INACTION & RESEARCH SHORTCOMINGS

The negative effects of neonicotinoids on pollinators is widely studied and has initiated calls for the EPA to initiate further restrictions. (The planned completion for the EPA’s Schedule of Review is 2024.) Anchored in scientific research about pollinator mass death, a 2023 California bill that begins in 2025 will “prohibit a person from selling, possessing, or using a pesticide containing neonicotinoid pesticides.”¹¹ Indeed this is a major step in countering the substantial biological interference caused by neonicotinoids.

ABC and partners contend that beyond causing ecological damage to pollinators, neonicotinoids pose a grave risk to granivorous vertebrates such as birds as well as the benthic invertebrates that many birds use for food source. Mineau argues that EPA regulators have underestimated the toxicity of neonicotinoids, ignoring critical data about its dangers and making critical errors in interpreting scientific literature. Mineau describes this as a ‘soft ride’ through the regulation process at the EPA, revealing glaring discrepancies between the scientific literature that studies neonicotinoids and the regulations imposed on their use by the EPA. Mineau writes, ”For imidacloprid, we believe that a scientifically defensible reference level for acute invertebrate effects is approximately 0.2 ug/l…in contrast, the EPA’s regulatory and non-regulatory reference levels are set at 35 ug/l.”¹²

A 2017 petition followed by a 2021 lawsuit against the EPA “requested pesticide-coated seeds receive the same scrutiny as other pesticide applications.” However, the EPA upheld its policy that “treated articles” are exempt from the oversight mandated in the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act.¹³ Claiming causal links between pesticide use and bird population decline is difficult due to fractured data: “data recorded at the molecular, cellular, physiological, or individual level on the one hand, and records of population declines or altered community structure in areas with high pesticide input or persistence on the other hand.”¹⁴ For example, Mineau points to the difficulty in establishing links between the impact of neonicotinoids on declining insect populations and declining bird populations. However, he writes, “it would be foolhardy to argue that dramatic losses of insect biomass from ecosystems is not going to have potential consequences on the integrity of those ecosystems.”¹⁵

There is further debate about the proper data metric endpoints used to assess acute toxicity of neonicotinoids in birds. Mineau argues that the typical EPA method for measuring acute toxicity in birds follows body weight scaling instead of species sensitivity distributions. “One of the serious failings of current risk assessment is the underestimation of interspecies variation in pesticide susceptibility…it has been shown that sensitive bird species are under-protected.” This leads to arbitrary results in which “the toxicity of different pesticides is ranked based on luck of the draw.”¹⁶

Mineau argues for increased research as well as regulatory action that considers these expanded negative effects of neonicotinoids. In summary, Mineau identifies the following as major concerns with policymakers lack of reconciliation for these pesticides:

• regulatory procedures are scientifically deficient and prone to the vagaries of chance

• risk managers appear to place minimal weight on concerns raised by environmental scientists who carry out the scientific evaluations of the products

• despite all the red flags, regulators are adding to the list of permissible uses

• neonicotinoids –the most heavily used insecticides in the world–are systemic products that are extremely persistent and very much prone to runoff and groundwater infiltration

• some neonicotinoids are capable of causing lethal intoxications and all are predicted to cause reproductive dysfunction in birds

• where we have looked, we have found broad-scale aquatic contamination at levels expected to cause impacts on aquatic food chains

• any future reevaluation of these products appears to focus solely on pollinator toxicity. The seriousness of pollinator losses should not be underestimated, but there is much more at stake.¹⁷

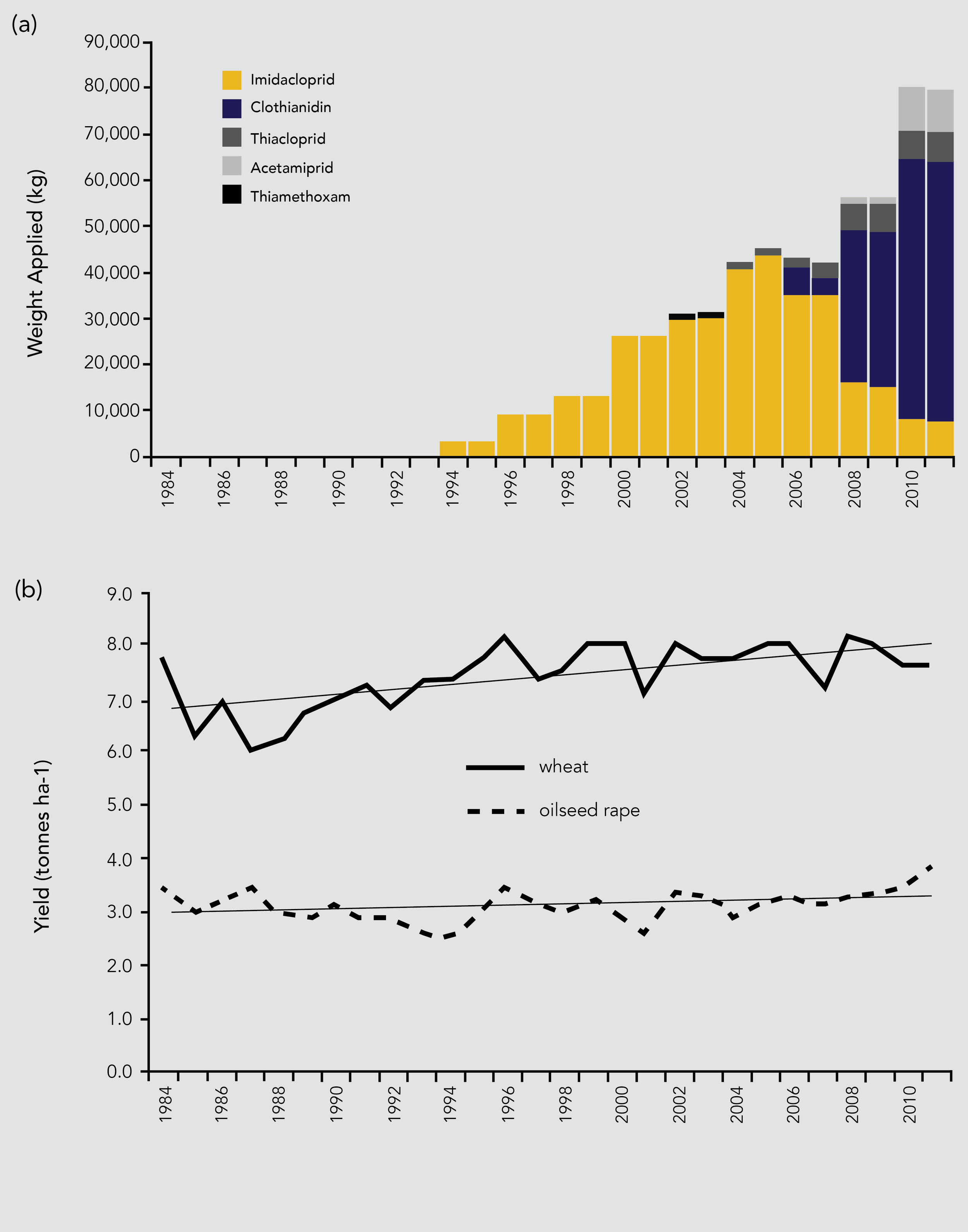

Fig 1. (a) Annual usage of neonicotinoid insecticides in the UK. Upon their introduction, use has steadily grown. (b) Despite the increase in neonicotinoid use, wheat and oilseed rape crops yields have remained steady. (Data from Journal of Applied Ecology.)²¹

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT (IPM)

Other than pursuing better research and stricter regulations by the EPA, the fight against neonicotinoids must happen on the ground, both at the scale of the farm and the scale of the watershed.

Integrated pest management (IPM) or integrated pest and pollinator management (IPPM) offers an excellent framework for reducing the use of neonicotinoids. IPM may incorporate the limited use of pesticides but only upon the observation of pests in crops: “monitoring pest populations to indicate when treatment is necessary, avoiding broad spectrum pesticides wherever possible and avoiding the use of pesticides that persist in the environment.”¹⁸ Goulson argues that the prophylactic use of broad-spectrum pesticides (i.e. neonicotinoid seed dressing) goes against the long-established principles of IPM, stripping agency away from farmers to employ site-specific pest control strategies that promote biodiversity, pollination, nutrient cycling, and microbial soil health.

IPM strategies underlie an understanding that there is no ‘silver bullet’ solution to pest control, but rather a series of innovations must be developed, and farmers must employ combinations of IPM strategies as determined by active monitoring of crops. “The idea behind IPM is that combining different practices together overcomes the shortcomings of individual practices.”¹⁹ For example A. Gamliel points to a popular combination of “fumigation or solarization with biocontrol agents” in controlling pests while also maintaining “the microbial balance in soils.”²⁰ Additional IPM approaches include using resistant crop cultivars, incorporating sustainable cultivation practices (crop rotation, intercropping, undersewing,) relying on mechanical weeding labor, and employing biopesticides or biocontrol with natural enemies (e.g. ladybugs attack aphids.²²)

Inevitably, tougher regulation on conventional pesticide markets will create a market space for biopesticide companies, and Chandler contends that “biopesticides are not given due attention in debates on sustainability.”²³ The biggest advances in biopesticide development will come “through exploiting knowledge of the genomes of pests and their natural enemies.”²⁴ Already, 63% of maize planted “consists of genetically modified (GM) varieties expressing Bt S-endotoxin gene,” and the EPA includes transgenes in its categorization of biopesticides.²⁵ Those with goals to eliminate neonicotinoids should have an open mind as to where biopesticide technologies might develop.

There are an estimated 67,000 crop pest species that together cause a 40% reduction in the world’s crop yield. While neonicotinoids are unquestionably effective in killing these pests, it is very much in dispute as to whether their use actually leads to higher crop yields.²⁶ There exists a false dichotomy between the conservation of natural resources and agricultural productivity. In fact, there is growing evidence that “substantially lower pesticide inputs result in similar yields.”²⁷ An analysis of 62 IPM projects in 26 countries concluded that “60% of the projects resulted in an average 75% reduction of pesticide use and an average 40% increase in crop yields.”²⁸

From a study of 1.3 million hectares in the UK, where nearly 100% of seeds are coated by neonicotinoids, it was found that there is no correlation between the use of neonicotinoids and crop yields. As explored in Figure One, there has been no significant rise in oilseed rape yields since (neonicotinoid) introduction, while winter wheat yields have only slightly risen.²⁹ Might this lead to a hypothesis that effective pest control could be achieved even when pesticide levels are significantly reduced?

Across four growing seasons, Pecenka et al. use research stations across Indiana to explore a rotation system of corn and watermelon. They study paired sites of conventional management (CM) with neonicotinoid-treated seeds and calendar-based insecticides, compared with an IPM approach with untreated seeds and insecticide treatments to watermelon only as needed. The results are compelling. “Despite higher pest densities and/or damage in both crops, IPM-managed pests rarely reached economic thresholds, resulting in 95% lower insecticide use…In IPM corn, the absence of a neonicotinoid seed treatment had no impact on yields, whereas IPM watermelon experienced a 129% increase in flower visitation rate by pollinators, resulting in 26% higher yields.”³⁰ The study found almost no difference in crop yields, showing that, “for the corn-watermelon rotation system they study, the adoption of IPM can reduce costs and pesticide residues by reducing insecticides by 95%”³¹

For those environmental purists who cringe at any proposal to reduce rather than eliminate pesticide use, I suggest the term “reduce” is a vast understatement considering Pacenka’s findings in Indiana. 95% reduction in pesticide use through employing IPM strategies is far from negligible. As David Chandler writes: the public/mass media debate about the future of agriculture has become increasingly polarized into a conflict between supporters of ‘conventional’ versus ‘organic’ farming rather than considering what practices should be adopted from all farming systems to make crop protection more sustainable.”³²

BIBLIOGRAPHY & CITATIONS

—1 https://www.epa.gov/caddis/case-ddt-revisiting-impairment

—2 Rosenberg, Kenneth V. et al. “Decline of the North American Avifauna.” Science 366,120-124(2019).DOI:10.1126/science.aaw1313. p.2

—3 Ibid, p.2

—4 Kern, Hardy. “This Loophole Allows Pesticide-Coated Seeds to Kill Birds. It’s Time to Close It.” EHN. Nov. 4, 2022. https://www.ehn.org/pesticides-and-birds-2658578889.html

—5 Goulson, Dave. “An Overview of the Environmental Risks Posed by Neonicotinoid Insecticides.” Journal of Applied Ecology, August 2013, Vol. 50, No.4.p.978

—6 Ibid, p. 971

—7 Ibid, p. 975

—8 Mineau, Pierre. “The Impact of the Nation’s Most Widely Used Insecticides on Birds.” American Bird Conservancy, The Plains, VA, p.97 (2013) p. 25

—9. Ibid, p. 26

—10 Goulson, p. 982

—11 https://digitaldemocracy.calmatters.org/bills/ca_202320240ab363

—12 Mineau, p.8

—13 Kern, p.3

—14 Kohler, Heinz-R. “Wildlife Ecotoxicology of Pesticides: Can We Track Effects to the Population Level and Beyond?” Science, 16 August 2013, New Series, Vol. 341, No. 6147.p. 672

—15 Mineau, p.8

—16 Ibid, p. 17

—17 Ibid, p. 9

—18 Goulson, p. 984

—19 Chandler, David et al. “The Development, Regulation and USe of Biopesticides for Integrated Pest Management.” Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 12 July 2011, Vol. 366, No. 1573.p. 1988

—20 Goulson, p. 798

—21 Gamliel, A. “Application Aspects of Integrated Pest Management.” Journal of Plant Pathology, December 2010, Vol. 92, No. 4, Supplement. p. 23

—22 Chandler, p. 1987

—23 Ibid p. 1995

—24 Ibid, p. 1994

—25 Ibid, p. 1994

—26 Ibid, p1987

—27 Pecenka, Job R. et al.”IPM Reduces Insecticide Applications by 95% While Maintaining or Enhancing Crop Yields Through Wild Pollinator Conservation.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, November 2, 2001, Vol. 118, No.44. p. 7

—28 Chandler, 1988

—29 Goulson, p. 579

—30 Ibid, p.579

—31 Isaacs, Rufus. “Integrated Pest Management Can Still Deliver On Its Promise With Help from the Bees.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, November 30, 2021, Vol. 118, No. 48. p. 3

—32 Chandler, p. 1995